A favorite topic on the blogosphere is whether or not Seediq Bale is an historically accurate take on the Wushe Incident. Some details, at least, are inaccurate, and people have some questions for the director Wei Te-sheng. For instance: Why is Mona Rudao at events in the early 1900s he didn’t attend (人止關 in 1902 and 姊妹原 in 1903)? Why does Mona Rudao shoot at Seediq women when there’s no historical evidence for it and when it goes against gaya – tribal tradition or teaching? Where does the child warrior Pawan Nawi come from? And so forth.

All posts by darryl

Mona Rudao’s scars: epic identity in “Seediq Bale”

Commentary on the film Seediq Bale often relates it to Taiwan identity. Leaping the fifty years from the Wushe Incident (1930) to Taiwan nationalism (1980s) might seem like a non sequitur or anachronistic, but many have made the leap. According to The Economist, “its message of a unique, empowering Taiwanese identity is unmistakable.” I found this statement very irritating when I read it. What business does anyone have relating a Seediq resistance against the Japanese to Taiwan identity? I’ll address the issue of the supposed connection between Seediq Bale and Taiwan identity in a roundabout way, by exploring Seediq Bale as an epic film. It seems to me that the film’s message is of an epic identity, not necessarily an empowering one.

Nativization and Foreignization in the Translation of “Seediq Bale”

The epic film Seediq Bale: Warriors of the Rainbow Bridge is of particular interest to translators because it’s in the Taiwanese aboriginal language Seediq. As a Chinese-English literary translator I’m naturally interested in problems of translation in the film. Unfortunately, I don’t know the Seediq language. Translators know they should comment on languages they know well; but I’m going to go out on a limb here and comment on one issue of translation in Seediq Bale: the title of the film. Then I’ll use the nativization-foreignization continuum from translation theory to comment on different translations of the title.

“Seediq Bale” as a primitivist film

Seediq Bale is the biggest Taiwan film ever and the story of an indigenous resistance (against the Japanese in central Taiwan in 1930). As such, it reminds one of Avatar. Having spent many childhood nights reading Call of the Wild to the light of the moon, and many days in early adulthood reading Joseph Campbell – the great Primitivist and Orientalist – I’m embarrassed to admit that I came out of Avatar starry-eyed; Avatar is calculated to appeal to people like me with a “primitivist” tendency. It speaks, in a highly commercialized, packaged, unthreatening and, on second and third viewings, irritating way to longings in the wayward heart of modern man. Seediq Bale, for everything else that one might say about it, speaks to those same longings.

The Chinese connection in Taiwan’s first indigenous film

In Taiwan’s first indigenous film, Finding Sayun, there are two casting assistant/cameraman characters from Beijing, as well as a director from Beijing. The director from Beijing never appears on screen. We only hear his voice as he watches the footage recorded by his Taiwanese casting director. What are these mainlanders doing in a Taiwan indigenous film? One reviewer complains the Chinese connection is irrelevant and was probably included to attract Chinese investment. Another possibility is that the director Laha Mebow wanted to attract Chinese tourists to the village. B&B tourism is part of the marketing of the film. I don’t know if Chinese tourists stay in B&Bs, but there are now a lot of Chinese tourists visiting Taiwan. What if the investor put pressure on the director to change the film in accordance to mainland audience expectations? What if the director put on rose-colored glasses to make her village attractive to the mainlanders? These are delicate questions. I was too afraid to ask them. So, I asked the director via e-mail what the mainlanders are doing in her film. Suffice it to say, the director encouraged me to find the meaning of the Chinese connection in the film itself rather than the film’s investment structure or marketing strategy.

It seems to me that rather than declare the mainland Chinese presence in Finding Sayun irrelevant we should try and make sense of it.

Taiwan’s first indigenous film? Continuum and either/or definitions of “indigenous film”

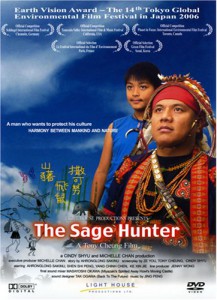

In an article on the recent Orchid Island film Waiting for the Flying Fish, which is about but not by Taiwan’s indigenous peoples, Prof. Anita Wen-hsin Chang called for funding for local films by indigenous directors. Finding Sayun, directed by the indigenous woman Laha Mebow, claims (on the film poster) to be the kind of film Prof. Chang has been waiting for: a local film with an indigenous director. Therehas been significant indigenous involvement in other films, including this year’s “epic” about the Wushe uprising in 1930, Seediq Bale. A better example is The Sage Hunter, starring the Taiwan indigenous writer Sakinu and based on his writings.

If Finding Sayun is Taiwan’s first indigenous film, it is Taiwan’s first contribution to the growing corpus of global indigenous film. According to Houston Wood, the author of Native Features: Indigenous Film from Around the World, the first indigenous film was Richardson Morse’s 1972 adaptation M. Scott Momaday’s novel House Made of Dawn. The first feature by an indigenous woman was the Australian Tracey Moffat’s beDevil in 1993. A Chinese/Atayal language indigenous film with limited distribution (even in Taiwan) like Finding Sayun is not likely to make it onto the radar of a scholar like Wood. This is not a criticism of Wood, who had his work cut out for him trying to cover indigenous films in English speaking countries.

But what does it mean to claim that a film is indigenous?

“Finding Sayun” and aboriginal romance films

[Savage Minds welcomes guest blogger Darryl Sterk.]

Finding Sayun is a superb new anti-aboriginal romance film by Laha Mebow (陳潔瑤), a Taiwan indigenous director. The film revisits the 1943 Japanese propaganda film Sayon’s Bell about an indigenous girl from Nan-ao, a “rural township” in northeastern Taiwan, who drowned trying to carry luggage across a river for the man she adored: a departing Japanese officer. (Sayon and Sayun are two different transliterations of the same name.) Sayon’s Bell wanted to reassure the Japanese public that, a decade after the Wushe uprising in 1930, Taiwan’s indigenous peoples had been converted to imperial subjects, and to convince aboriginal braves to fight for the emperor: it would be hard to resist after hearing Sayun singing the inspiring Song of the Taiwan Soldiers: