By Uzma Z. Rizvi

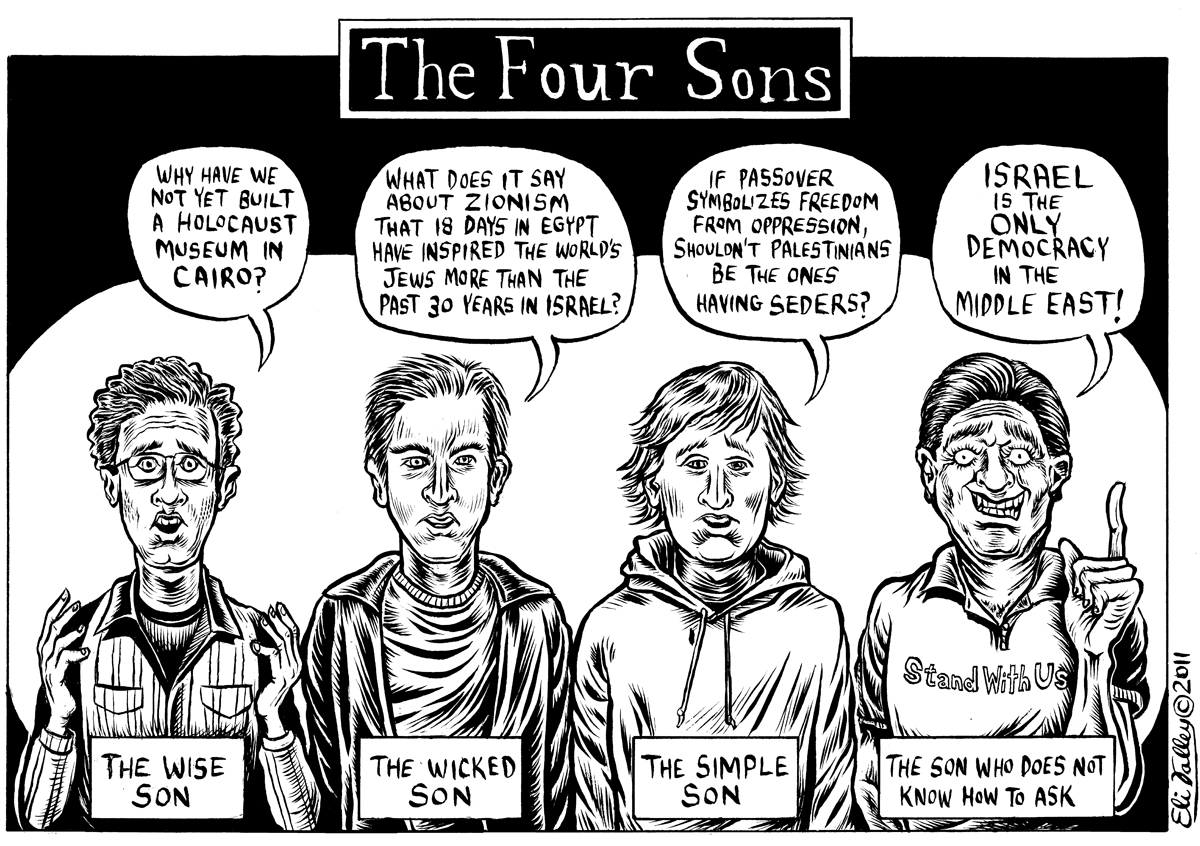

What happens to our praxis once we start from a place of acknowledging difference in our persons, our histories, our bodies, and our aesthetics? This text starts from a standpoint of curiosity, consideration, and mindfulness as we explore how, who and what we are, inform structures we create. The moment and place of knowing requires a certain slowness to enter into our thoughts, movements, and research, allowing for nuance and precision, for care and humility, and for an aesthetic of difference to incubate our praxis. Once we allow our work to breathe, to reflect, to sense difference, it transforms structures around it or structures created through it.[1] The act of research becomes praxis through which critical awareness of one’s own condition and the condition of others comes into high relief. One aspect of this praxis includes bodies co-producing the work. There are intricate processes that situate us between theory and practice as praxis, which must begin to take into account the many ways in which we are identified, the modes of address, our different bodies, and varied epistemologies.

Intersectionality allows us to occupy that praxis and standpoint critically.[2] It takes into account systems of oppression within the world that hold marginalized people in place (often at an inferior position) in multiple ways. It is not a new idea to acknowledge that our vectors of identity (race, class, ethnicity/gender/body, et cetera) inform how we experience and consider the world, but what is significant in intersectionality is that that place holding happens in different ways at different times and for different reasons. On the flip side, it also means that privilege manifests itself in similarly multifaceted forms. If, due to your body experience, you have never had to question how the world looks at your race/class/ethnicity/gender/body, or if that has never impacted the way the world identifies your research or work, you should know that that is a privileged experience. And that privilege or lack thereof, informs you and your praxis.

Continue reading →

A podcast and blog walk into a bar…

A podcast and blog walk into a bar… Anthro/Zine | April 2016

Anthro/Zine | April 2016

.

.