Post by Laia Pujol-Tost:

Archaeology is mostly about materiality. Its epistemological foundation is based on the relationship between humans and the material culture. Some of this objects, will later be displayed in museums to convey interpretations of the past. Yet, as Yannis Hamilakis and other authors have argued, Archaeology is a modern “science”. As such, it is mostly about the eye, and little about the body. On site, it mostly records and analyses visual, spatial, geometrical features. At the museum, this has meant a universal rule of not touching, and objects are isolated in showcases, for the sake of… mutual protection.

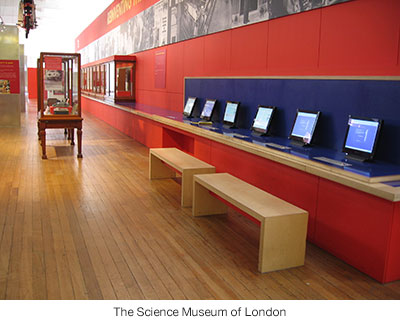

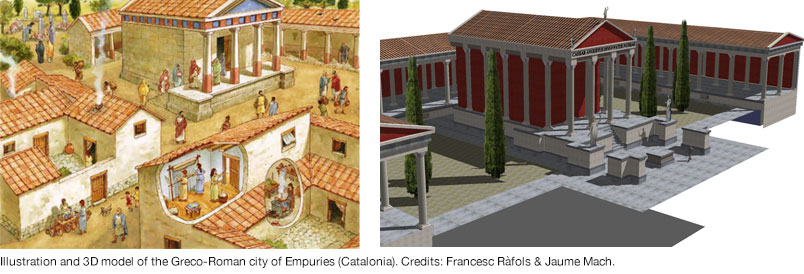

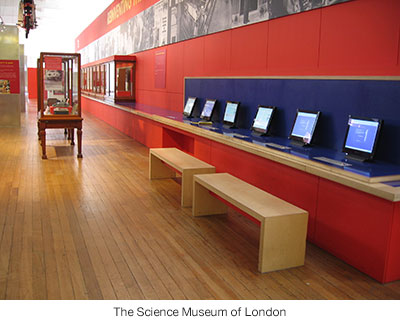

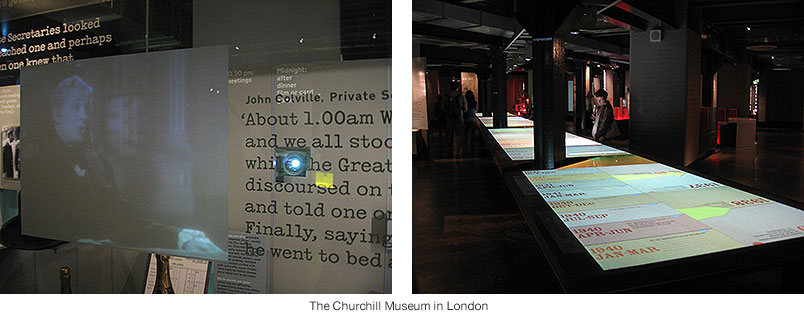

Then came Information and Communication Technologies (before they were called Digital Media), which under the promise of increased accessibility, interaction and engagement, reduced archaeological heritage even more to image and visualization: it had been digitalized; that is, de-materialized and even “de-musealized”. A series of evaluations conducted in museums since the 90s evidenced a conflict between the exhibition and the new media. The main reason being, as Christian Heath and Dirk vom Lehn pointed out, that exhibitions and computers belonged to different communication paradigms.

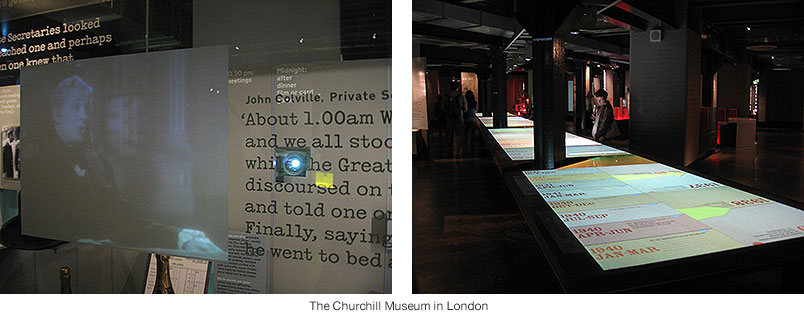

Around that time, several studies conducted in different European museums led me to the conclusion that the best way to integrate digital technologies was to stop just placing computers in exhibitions, and instead re-design the interfaces purposefully for such environments. Yet, what happened was the advent of mobile devices.

Meanwhile, some researchers working in the highly interdisciplinary field of Human-Computer Interaction started advocating for more natural ways to interact with computers. As a result, a new field called Tangible or Embodied Interaction arose around the 1990s. In this context, the concept of “Tangible User Interface” was developed. In TUIs, the interface is not anymore a PC but an (everyday) object. This takes advantage of the human capacity to manipulate objects, and allows a better integration with the context of use. Since the 2000s, labs used occasionally the cultural field as test bed; until 2013, when the first EU-funded project specifically devoted to tangible interactive experiences in Cultural Heritage settings was set up.

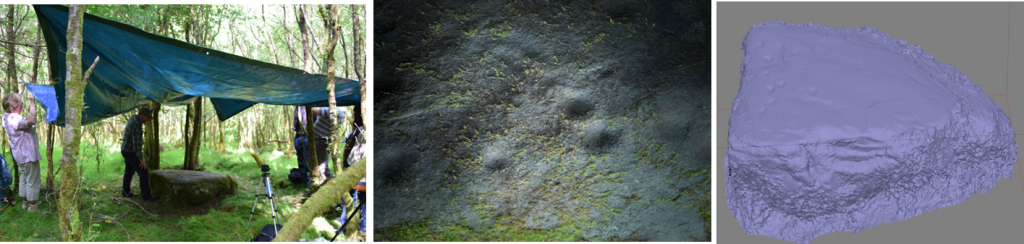

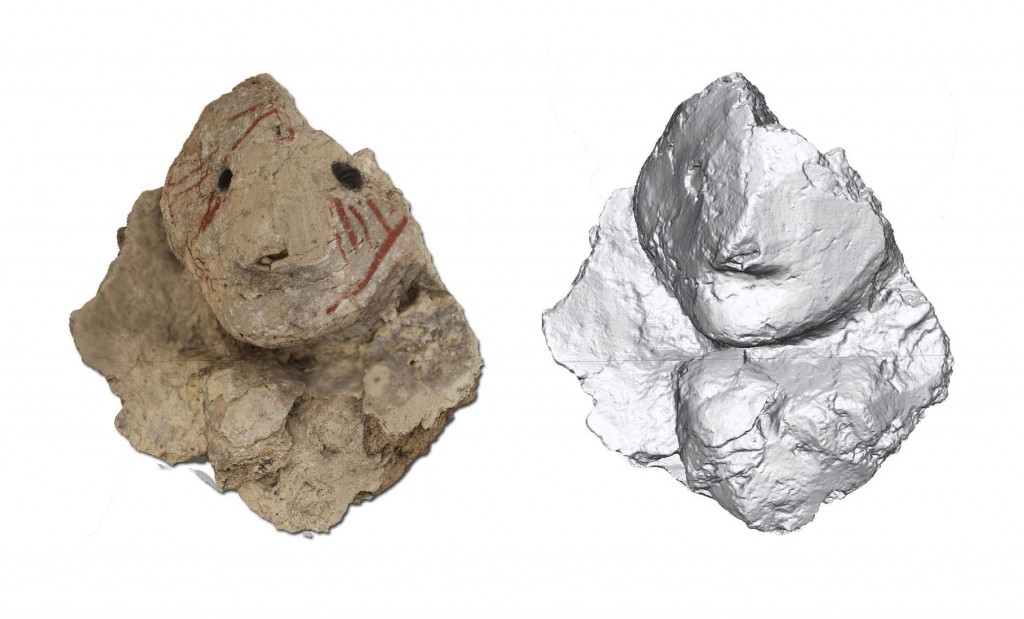

Now 3D printing has become the hype. As it happened with computers in the previous century, this technology is not new: it has been used in the engineering field for rapid-prototyping since the 1980s. But only recently it has become accessible to markets. Its applications are manifold: engineering, clothing, food, housing, health… But more than that, its implications regarding traditional product design, production and distribution chains are so enormous, that some people already talk about additive manufacturing being the next industrial revolution. The Cultural Heritage field has not been indifferent to this development. For example, the Smithsonian has started the X3D project, aimed at digitalizing and allowing the 3D printing of its collections. In the academic domain, some sessions at the EAA conference dealt with the implications of 3D printed replicas for Archaeology. Finally, the first mixed exhibits have appeared in European museums the last years, used either as mediators, smart replicas, top tables for shared exploration and gaming, or as full-body interactive environments.

I am so excited about it! Does this mean that we may finally close the circle and, after such a long history of “voyeurism”, fully acknowledge materiality and tangibility in the cultural heritage field? It is interesting to note that, as it happened before with interaction or storytelling, we needed the pressure of the digital revolution to (re)discover or finally accept elements that already existed in the museums field. Still, I believe there is a big potential in this area, more than with digital media, and this is exactly what I am starting to investigate now. On the one hand, the specific advantages of smart replicas or tangible exhibits for Cultural Heritage settings. I have adapted Eva Hornecker’s overview of Tangible Interaction to list the following features:

- Appreciation of the materiality of the real object.

- Direct manipulation instead of just visualization.

- Performative action instead of passive gaze.

- Natural interaction without added symbolism.

- Natural integration in the exhibition environment.

- Non-fragmented visibility.

- Suitability for exploration in group.

- Personalization (especially suitable for children).

On the other hand, I am concerned about the strategies and threats for their adoption in museums. The experience shows that, as costs decrease, the availability and penetration of technologies increase. Still, the problem is designing and maintaining high-tech exhibits. Most museums tend to outsource digital media projects; but this has more often than not proven to be a bittersweet experience in terms of budget, sustainability, end-product, workflow, etc. Institutions are currently implementing different solutions. For example, EU-funded projects emphasize the creation of do-it-yourself authoring tools. Also, the big museums in the USA and Europe give strong support to the creation of their own digital media departments, so that such experiences can be fully developed in-house.

Yet, as we witness again a concern similar to supposed threat posed by the virtual to the brick-and-mortar museum, we first need to complete the unfinished debate around the concept of authenticity in cultural heritage. In my opinion, the problem to be solved is not with smart replicas (which, following Bernard Deloche’s taxonomy, only act as analogical or analytical substitutes), but with the role of originals in the age of information, commodification, and globalization. However, this is a discussion for another time and place.

(Part of this month’s Analog/Digital series, thanks to Savage Minds for hosting!)