There is a touch-screen internet networked television mounted on a wall in a middle class living room. You turn it on with a touch and rows of applications organized as colorful little boxes are revealed. You are familiar with the choices because they are the same as what is displayed on your mobile phone. In this apparent cornucopia of choices are hundreds of apps to click to watch CBS dramas, New York Times video segments, CNET interview programs, Mashable tweetfeeds, and CNN live broadcasts. Or you can rent a movie from Apple’s iTV, Google TV, Amazon, or YouTube Rentals suggested to you based on your shopping preferences as gathered from your GPS ambulations. You want to show your friend a funny video that was recommended to you earlier in the day so you click on the YouTube Partners app and it appears on the screen.

You crave a different meme, something old school, circa around 2009. You could go to the YouTube Classics app, but strangely your favorite video never made it to 100 million views and so wasn’t promoted to YouTube Classics. Your television system is connected to the internet but the public internet browser app is buried in the systems folder on your networked TV. Besides, if you could find the browser app you can’t find a keyboard to type out search terms. You drop the idea of following a personal impulse and go with what you can see through the window of the professionally curated suite of applications.

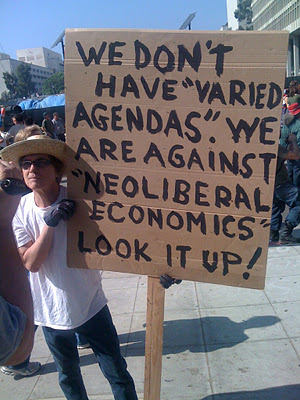

This description of a limited and safe television viewing experience of the future is meant to evoke a feeling that the limitless content and freedom that we associate with internet video is quickly being truncated by the hardware and software engineers in cahoots with the content app designers to make a much more safe, convenient, and professional internet. This is quite easy to see in the world of internet video—once the land of the most subversive, graphic, and comic content possible—is now being overhauled by professionals producing, curating, optimizing, and streaming ‘quality’ videos to homes on proprietary hardware. Many of us interested in the democratization of media, the absence of conglomerate consolidation, the presence of “generative” digital tools, video activism, and indigenous media should be concerned by these trends. This era will be seen as the historical pioneering era of internet video idealism (2005-2009).

Earlier this month, in re-introducing Apple’s internet connected TV set top box, the iTV, Steve Jobs claimed that people want “Hollywood movies and TV shows…they don’t want amateur hour.” What Jobs is saying is that we are entering a new era of professionalism—gone is the wild Darwinian kingdom of video memes, the meritocracy of the rabble rousers, the open platforms equally prioritizing the talented poor as well as the rich. Jobs has never been one to parrot the ‘democratization of media’ ideal. Never one championing collective design or the wisdom of the crowd (if only to fanatically buy his hardware), Jobs firmly believes in the auteur, the singular virtuosity of the genius designer, engineer, and director to make a professionally superior object of art and function. The upcoming golden age of ‘quality’ professional content will be ruled by Jobs and his ilk at HBO, Pixar, Hulu, LG, and Vizio.

Jobs’ vision is but one example showing that the pioneer age of the free and open culture of internet video is ending. Current TV, from 2005-2008, aired 30% user-generated documentaries and produced a cable television network that modeled democracy. Today they are taking pitches only from top Hollywood TV producers. The YouTube Partner’s program, like the very talented Next New Networks—the talent agents for Obama Girl and Auto-Tune the News—culls the ripest and most viral video producers from YouTube and optimizes them for the attachment of profitable commercials. Once pruned and preened, these YouTube cybercelebrities are promoted on the hottest real estate on the internet, YouTube’s frontpage, making 6-figures for themselves while finally making YouTube profitable.

Subcultural activities going mainstream is nothing new, the radical 60s cable guerilla television crew, TVTV, went from making ironic investigations into the 1972 Republican and Democratic conventions to making regular puff pieces for broadcast. World of Wonder, the queerest television company in Hollywood, has been bringing the sexual and gender underground to mainstream cable television for decades. For examples, see my documentary on World of Wonder.

But it is the first example regarding IPTV—internet-based direct to consumer ‘television’ such as Apple’s iTV—that will bring only the best of internet video to the home that most concerns me. The professional domestication of internet video in the home, I fear, will forever wipe out the memory of the wicked and subversive video memes of the YouTube past. With it will go the very ethos of participatory video culture. My colleagues in the Open Video movement can collectively design the hell out of open video apps, editing systems, protocols, and videos standards but no one using these free and open source video systems will be seen if proprietary IPTV covers both software and hardware, internet and television, in both the home and the office.

The process I am describing can best be articulated as a historical process of professionalization. The wild world of amateur video—its production, promotion, and distribution procedures—is moving from the realm of prototyping, beta-testing, and experimentation to expert production, algorithmic optimization, and alpha release five years after its debut on YouTube and Current TV. This professionalization is a historical result of 5 years of industrial development, individual trial and error, and profit-focused talent agencies and creative thinktanks. It is also a product of the historical convergence of the internet and television hardware, as well as the corporate consolidation of content and software around the idea of the app—a professionally designed hardware/software/content peephole into a small fraction of the internet. More anthropological however is the historical transformation of the subculture into the culture. This has been happening forever and is the engine of popular culture and we shouldn’t be so hip and retro as to bemoan it. But we should be concerned with the loss of that realm of artistic and political potential encoded in the free and open internet. The “golden age” to follow this pioneering phase will be as innovative as the golden age of television as we welcome the equivalent of I Love Lucy, Friends, and Lost and along with it the return to spectatorism, canned laughter, and the proliferation of middle class values.

py to oblige Stelter’s creativity and I’ll accept the flattery with the imitation. Today, I will continue the analysis of this crisis in the direction of looking at the relationship between individual and institutional cultural capital.

py to oblige Stelter’s creativity and I’ll accept the flattery with the imitation. Today, I will continue the analysis of this crisis in the direction of looking at the relationship between individual and institutional cultural capital.