In 2006, according to Time Magazine, the theory of technoindividualism “took a serious beating.” In electing You to the position of the Person of the Year, Time prophesized the fourth discourse of internet historiographical revisionism following President Obama’s statement. It was not the state, corporations, or genius insiders who made the internet, nonfiction best seller author and transhuman apologist Steven Johnson claimed in the New York Times, but Us who built the internet. Continue reading

All posts by Adam Fish

Who Built the Internet? Studly Genius Individuals! (Part 4)

Thus far Crovitz’s and Manjoo’s positions are located within modernist historiographical and liberal conceptions over the battles of freedom, with network technology as a proxy battlefield, and the role of states and corporations as extenders or inhibitors of those freedoms. The third leg of this modernist battle has to be initiated by the sole genius and his impact on the development of the internet. Continue reading

Who Built the Internet? The State! (Part 3)

Despite Crovitz’s best wishes, Taylor’s Xerox PARC Ethernet didn’t become the internet as Slate’s Farhad Manjoo and Time’s Harry McCracken explain. Two days later, Manjoo rebutted Crovitz’s “almost hysterically false” argument. Aligning with given wisdom, Manjoo stated that the internet was financed and created by the US government. Despite being more historically accurate than Crovitz’s argument this statement is also political. In reminding the residents of Roanoke of the government’s role in the founding of the internet, President Obama, according to Manjoo, “argued that wealthy business people owe some of their success to the government’s investment in education and basic infrastructure.” This argument is progressive, social democratic, or socially liberal–advocating for responsible taxation and the shared burden of national identification, and is therefore a political narrative opposed to the Darwinism of technolibertarianism expounded by the Technology Liberation Front. Continue reading

Who Built the Internet? Corporations! (Part 2)

Obama may have gaffed, neoliberal assistant editors at Fox News and the Republican National Committee, exploitatively edited, repurposed, and exaggerated the speech, but it was Wall Street Journal writer L. Gordon Crovitz who mistook the misedits as evidence for US executive branch internet revisionism. Crovitz, ex-publisher of the Journal, ex-executive at Dow Jones, and social media start-up entrepreneur, attacked President Obama’s statement that the internet was funded and engineered by the federal government. “It’s an urban legend that the government launched the Internet,” he idiosyncratically declared. The crux of Crovitz’s argument was focused on Robert Taylor, who ran the ARPAnet, a US DAPRA project that connected computer networks to computer networks. Taylor, according to Crovitz, stated that this proto-internet, “was not an Internet.” And therefore, most importantly for Crovitz, this meant that President Obama was dead wrong, Taylor, a federal employee at this time did not help to invent the internet. The internet was not made by engineers paid by public but private hands. Crovitz’s twist on the accepted story is that Taylor later made a different internet, ethernet, at Xerox PARC where we worked after DARPA. And it was Ethernet that became the internet. Continue reading

The Internet: Who Built That?! (Part 1)

[This is a part of a six part blog on four debates about the origins of the internet. Please see all six posts here.]

Suddenly in the wake of President Barack Obama’s untimely but ultimately non-fatal but non-optimal grammar, the question of who made what when and how much the government had or had not to do with it was up for debate. Resisting the attacks on all things federal at the tail end of the 2012 US presidential election, President Obama said to a crowd in Roanoke, Virginia on July 13, 2012:

“The internet didn’t get invented on its own. Government research created the internet so that all companies could make money off the internet.” Continue reading

Silos of Casino Capitalism

Something called a “silo” kept cropping up in my field research with media reform broadcasters throughout 2012. At the National Conference of Media Reform in 2011 I attended a panel, “Getting Out of the Silo: Editing Video as a Community.” The organizer told me she was “looking to create an intersectional narrative of collaboration” with the panelists. “We are all living in our little silos,” said the general manager of a small television news network explaining how a possible partner rejected his overture for collaboration. Its “the silophication of the company,” said a vice president of a television news network of the process by which internet, television, and marketing divisions were not well-integrated while taking different approaches to the same product.

What is a Silo?

Silophication is most actively theorized by a person who straddles anthropology, global finance, and journalism: Dr. Gillian Tett, a Cambridge trained anthropologist and US managing editor of the Financial Times. Below I build theory through categorizing Tett’s use of the term silophication in her financial journalism critical of how regulator’s and banker’s silophication led to an absence of information sharing and the presence of a global financial crisis. Continue reading

Anthropology of this Century

I had the pleasure of interviewing Charles Stafford, Professor of Anthropology at the London School of Economics, about his new anthropology journal Anthropology of this Century. Click below to read the interview.

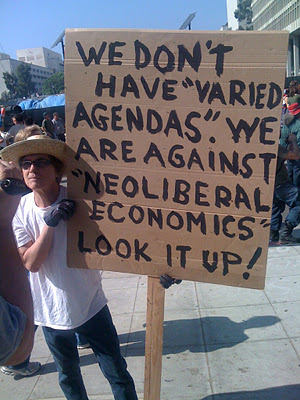

Paul Ryan’s Neoliberal Fantasy and Keith Olbermann’s Demise

Foucault asks “Can the market really have the power of formalization for both the state and society?” (Foucault 2008: 117, originally 1978-79). House Budget Chairman Rep. Paul Ryan is convinced it can. He outlines it happening in the 2012 and 2013 fiscal year budgets. The impact of this neoliberal fantasy on democracy is stated by Couldry: “‘Democracy’ operated on neoliberal principles is not democracy. For it has abandoned, as unnecessary, a vision of democracy as a form of social organization in which government’s legitimacy is measured by the degree to which it takes account of its citizens’ voices” (Couldry 2010: 64). What is the impact of the dearth of diverse progressive voices on public and private media within the hegemonic public sphere?

The Nation states that the GOP’s 2013 budget or the “Ryan Plan” helps the very wealthy, corporations, Pentagon, and health insurance companies while forcing the poor, elderly, disabled, and middle class to sacrifice (Zornick 2012). President Obama called the budget “social Darwinism.” A great term, curiously investigated by the Washington Post. Back in February, 2011, during the last federal budget battle, the New York Times claimed that the GOP targeted to slash funding for job training, environmental protection, disease control, crime protection, science, technology, education, and public media (Editorial 2011). It is a theory of classical liberalism that as these issues of national importance are proposed and debated it is fundamental to the workings of democracy that citizens have diverse information options. This is the job of journalists, newspapers, television news — “the media” — whose investigate capacities have been gutted by parent companies’ market fundamentalism and whose federal funding, when it barely existed, is under attack. Six bills were proposed in 2011 to eliminate federally funding PBS (Tomasic 2011). In this neoliberal media logic, if it fails the single criteria of increasing capital, it misses the cut.

The same week the draconian 2013 Ryan Plan was revealed saw the elimination of two paternalistic guardians of the “American public sphere” –the Media Access Project (MAP), a public interest law firm and 40-year veteran resisting the deregulation and privatization of public media resources. And, most dramatically, Keith Olbermann was fired from Current, a cable television news network. Like him or hate him, he is one of the few television newscasters willing to bluntly critique such instances of neoliberal governmentality on that most hegemonic if media systems: television. As both private public interest and not-for-profit public interest media institutions falter, and federally funded public media systems are assaulted, how will diversity in the American public sphere survive?

I need to briefly address the following normative notions: neoliberal governmentality and the hegemonic or American public sphere.

MAP and Olbermann focused on diversifying the programming within the hegemonic public sphere. They see themselves, their work, and their information as central to dominant national issues within a single American public sphere. They are not interested in producing the conditions for a subaltern counterpublic as Nancy Fraser (1992) describes. Their interest is in competing on a national-level with the likes of Fox News, MSNBC, and other media giants. MAP and Olbermann sought to contribute diverse voices into a single, national, or American public sphere. Does it exist? No. Fraser is right. There are overlapping fields of public spheres. But the hegemonic public sphere is a type of emic model or frame, non-existent on the level of day-to-day discourse, that these media reform broadcasters draw from. More abstract and less polemical, yet comparable with the concept of the “mainstream media,” the hegemonic public sphere is a goal or target for the progressive cultural interventions of these media reform broadcasters.

Foucault provides a cogent definition of neoliberal governmentality in his exquisitely readable lectures at the College de France in 1978-1979. “What is at issue” said Foucault, “is whether a market economy can in fact serve as the principle, form, and model for a state” (Foucault 2008: 117). The result is market statism, or corporatism, which, in an extreme version, is fascism. This is diametrically opposed to the social liberalism advocated by Olbermann and MAP in which the state is focused on non-market social projects. It isn’t corporate liberalism either where the government in public discourse supports social liberalism but that practice is performed by subsidized corporations (Streeter 1996). An example of corporate liberalism comes from the presumed GOP candidate for the 2012 presidential election. Governor Mitt Romney addressed a crowd at a primary campaign stop in Iowa in November. At this event Romney says he won’t gut the Corporation for Public Broadcasting but he will require it to “have advertisments.” Romney doesn’t want to “Kill Big Bird” he just wants it to be on life-support from American corporations. Rather, the Ryan Plan is neoliberal governmentality where social liberal projects are negated and replaced by market fundamentalism. It is this reduction of government functions to market logic that Olbermann and MAP once raged against.

So with the departure of Olbermann and MAP the monolithic American public sphere is less diverse and less capable of engineering the conditions for access for diverse voices. Nick Couldry’s Why Voice Matters: Culture and Politics after Neoliberalism (2010) directly addresses how neoliberal governmentality dampens voice through looking at US and UK television. He defines voice as referring to the process of individuals or communities using media to build reflexive and historical stories. Voice, for Couldry, is socially grounded, provides for reflexive agency and is an embodied force. Voice can be injured or denied by rationalities that perceive voice as an externality of market logic. Thus “valuing voice means valuing something that neoliberal rationality fails to count; it can therefore contribute to a counter-rationality against neoliberalism” (Couldry 2010: 12-13). Without Olbermann’s voice and MAP protecting the legal and political conditions for voicing, how will the American public sphere survive this assault by the flexible tactics of neoliberal governmentality?

@@@

Now, dear Reader, to reward you making it this far here are some hilarious videos that illustrate my points from the comic geniuses of Mitt Romney, President Obama, Cenk Uygur! Cue the laugh track after each video. Continue reading

How to Get a Job as an Anthropologist

Stop being an anthropologist.

Some of my mentors, none of which are in anthropology departments, prefer to say “trained as an anthropologist, so and so, investigates…” as opposed to “so and so is an anthropologist.” If you are on the job market this may be hard to do as you are likely to have just become a PhD wielding anthropologist for the first time in your life and quite proud of the moniker and achievement but the shift in self-definition is important for you and your future academic home, I would argue.

I just went through the whole job-hunting process before signing a contract on Monday to become a Lecturer in media and cultural studies in the Sociology Department at Lancaster University. I was able to apply for a silly amount of jobs, get a bunch of interviews and campus visit requests, and have some choices and grounds on which to do some humble negotiating. I think my trick was post-disciplinary research and (a considerable amount of) cross-disciplinary publishing. I could apply to communications, media studies, anthropology, information studies, STS, sociology, television studies, American studies, and internet studies. If I were desperate I could apply for archaeology and film production positions. Postdoctoral positions, particularly those financed by the Mellon, are all about interdisciplinarity as are jobs looking for digital humanities scholars.

So I’d encourage my fellow freshly minted ABDs and PhDs to begin seeing their research and their teaching across at least 4-5 large disciplines. Be able to realistically apply to 4-5 departments. One can put this together variously by publishing in different journals, collaborating with colleagues from different fields, or simply working the boundaries of one’s discipline in necessarily interdisciplinary ways. (All I can say is that I hope this is not my internalization of the precarity of neoliberal governmentality in the education sector.)

And there is something said for responding (in non-trendy and timeless ways!) to emergent patterns in industry, politics, and social movements. The departments recognize that what is in the news is what the students want to study. In my case this amounted to a recursive loop from the hype surrounding new media –Arab Spring, Anonymous, Wikileaks, SOPA, PIPA, and Occupy– to departments requesting applicants with expertise in social media and political movements. Oddly enough, if the academic job thing doesn’t work out this type of preparation in the now prepares oneself better for a post-academic profession. In academia the joy of investigating emergent practices is that there is no syllabus. You get to design your own. And in the classroom you are not pulling teeth, the issues are on students’ minds. It is relevant.

I may sound heretical to some of you by suggesting that post-anthropological disciplinary affiliations are necessary. But one gains much less than one loses by fundamentally aligning oneself with the orthodoxy of a specific discipline. One one hand, the qualitative and critical social sciences are converging. Critical theory and ethnographic or textual methods run across all the disciplines above. On the other hand, replicating the discourses specific to a discipline is important for the survival of that discipline and I am glad some people are monogamously “physical anthropologists” or whatnot. But my argument is that this practice of disciplinary orthodoxy is dangerously myopic for a discipline and puts the job hunter in a situation with few options. I preferred to bring scholarship from other disciplines to anthropology, and though it proved difficult to buck anthropological tradition by studying contemporary technoculture in America, it provided me a wider repertoire of skills that apparently translate into numerous disciplines and a blessed job offer.

Good luck! Tell us how it goes for you.

Digital Money, Mobile Media, and the Consequences of Granularity

Nicholas Negroponte famously insisted that the dotcom boomers, “Move bits, not atoms.” Ignorant of the atom heavy human bodies, neuron dense brains, and physical hardware needed to make and move those little bits, Negroponte’s ideal did become real in the industrial sectors dependent upon communication and economic transaction. In the communication sector, atomic newspapers have been replaced by bitly news stories. In the transactional sector, coins are a nuisance, few carry dollars, and I just paid for a haircut with a credit card adaptor on the scissor-wielder’s Droid phone.

The human consequences of the bitification of atoms go far beyond my bourgeois consumption. This shift, or what is could simply be called digitalization, when paired with their very material transportation systems or networked communication technologies, combines to form a powerful force that impacts local and global democracies and economies.

What are the local and political economics of granularity in the space shared between the fiduciary and the communicative? To understand the emergent political economy of the practices and discourses unifying around mobile media and digital money we need a shared language around the issue of granularity. Continue reading

Hackers, Hippies, and the Techno-Spiritualities of Silicon Valley

I had the pleasure of hanging out with Dutch anthropologist Dorien Zandbergen (PhD, Anthropology, Leiden University) in Sweden in October at an ESF Research Conference and learning about her fascinating research into the convergence of new age spirituality and new media discourses in and around Silicon Valley. I loved the idea of a Dutch anthropologist studying me and my friends in the eco-chic Burning Man hipster scene so I asked her to riff off of a few questions for this blog. Zandbergen talked about liminality, technoscience, the California ideology, ‘multiplicit style,’ secularization, studying sideways, liberalism, internet culture, ‘pronoia’, open-endedness, emergence, the neoliberal ideal of the autonomous self, the confluence of hackers and hippies in San Francisco, the usual…

(AF) What is New Edge and how did you conduct your fieldwork?

(DZ) The term New Edge fuses the notions ‘New Age’ and ‘edgy’, as in ‘edgy technologies’. In the late 1980s, founder of the ‘cyberpunk’ magazine Mondo 2000, Ken Goffman, used the term to refer both to the overlaps and the incompatibilities between the spiritual worldview of ‘New Agers’ and the ‘geeky’ worldview of the scientists and hackers of the San Francisco Bay Area. Such interactions were articulated in the overlapping scenes of Virtual Reality development, electronic dance, computer hacking and cyberpunk fiction. I borrowed the term New Edge to study the genealogy of cultural cross-overs between – simply put – the ‘hippies’ and the ‘hackers’ of the Bay Area, beginning with the 1960s and tracing it to the current (2008) moment. Continue reading

American Democracy?

Many scholars, activists, pundits, and even a few politicians agree that American democracy is in trouble. Many reasons are given–the raw punch of money in elections, a distracted, apathetic, or misinformed population, the absence of civic education, the specter of blind patriotism, the penal threat and painful reality of police brutality. The signs of collapsing democracy are obvious: the debt ceiling debacle, the recent Supercommittee failure, Citizen United v Federal Elections Commission, a US Congress with 9% approval ratings. Our Occupy mobilizations, and our “deeply democratic” (Appadurai 2001) methodology of the General Assembly inspired as it is by the anthropological knowledge translated through our colleague David Graeber, are reactions to the failure of the present incarnation of American democracy while exclaiming our desire, voice to voice, for a more humane social democracy.

Non-fiction information, knowledge, and “the news” are essential for citizens to make wise decisions regarding the future of a democratic state. The right to media is a human right and a public resource for democratic communication. But the media is a finite resource, limited in radio, television, and the internet and limited by the amount of subjective mental bandwidth we can personally process. In the United States this media resource was allocated by the state to corporations. These America corporations were given the right and responsibility to use the “airwaves.” Part of the bargain the government struck with these companies was that they could make massive profits if they worked in the public interest by informing and educating the citizens. This responsibility they have slowly neglected and we are today left with fiction parading as fact on television news. Citizen involvement in this corporately consolidated public sphere was promised but subtly ignored. The abused or misused power of corporate media is a significant reason why democracy is failing.

Television for the 99% & Reverse Media Imperialism

The Public Sphere of Occupy Wall Street

I keep returning to the public sphere as Habermas originally described it as I think about progressive political movements of today: Occupy Wall Street and its global dimensions, Anonymous and its more theatrical and political wing LulzSec, and progressive and independent cable television news network Current. Internet activism, television news punditry, and street-based social movements each work together implicitly or explicitly to constitute a larger public sphere. As scholars we need to resist the temptation of excluding one form of resistance as being inconsequential to social justice or to analysis and instead see all three as working together in a media ecology.

Anthropology Fox Meme

I spoke with undergraduate anthropology major Liz Quinlan about her tumblr site Fuck Yeah Anthropology Major Fox which feature macros like:

She had this to say: