A strong media push by the Sage Foundation has put Jennifer Lee and Min Zhou’s book The Asian American Achievement Paradox into the public sphere in the past couple of days, garnering an op-ed on CNN.com and an interview on Inside Higher Ed. The book — at least what I’ve been able to read of it so far — is excellent. Even better, it pushes back against the embarrassing, amateurish work of Amy Chua, which claims, in essence, that ‘Asians’ are successful because they are morally virtuous. Or rather, since the weird, deeply-seated Anglo-Protestant cultural currents that run the US are often disguised, because of their ‘cultural values’. Lee and Zhou are adamant that cultural values do not cause Asian American success, and should be commended for boiling down their research findings into headline — and then getting people to run it. But their alternate explanation of Asian American success will look to most people, and especially most anthropologists, essentially cultural. The book deserves discussion because of the way it frames the culture concept, studies ‘culture of success’ (and, lurking in the background, ‘culture of poverty’ ) arguments, and attempts to intervene in the public sphere. It is an excellent model for how anthropologists should approach a topic they often shy away from. But it’s an argument for culture not against it. Or rather, for a good understanding of culture rather than an essentialized and inadequate ethnoracial understanding of culture.

Tag Archives: Ethnicity

The Limits of the Virtuoso

Pierre Bourdieu, in his famous critique of structuralism from Outline of a Theory of Practice, says:

only a virtuoso with a perfect command of his “art of living” can play on all the resources inherent in the ambiguities and uncertainties of behavior and situation in order to produce the actions appropriate to each case, to do that of which people will say “There was nothing else to be done”, and do it the right way.

Two recent headline-grabbing stories, Caitlyn Jenner’s Vanity Fair cover and Rachel Dolezal getting outed by her parents as “white,” have served to highlight the limits to virtuoso performance: the boundaries our society places over the individual’s ability to perform gender and ethnicity. Continue reading

Three Clips on Language and Ethnicity

In 2012 I wrote a post, Seven Ways to Talk to a White Man in which I talked about how Taiwanese react to seeing a foreign-looking person speak Chinese. Here is a funny video from Japan which dramatizes the scenario I described as “Look at the Asian”:

More after the jump.

Continue reading

After Oak Creek: A Roundup

“On August 5, 2012, a mass shooting took place at a Sikh temple in Oak Creek, Wisconsin, with a single gunman killing six people and wounding four others. The gunman, Wade Michael Page, a white supremacist, shot several people at the temple, including a responding police officer. After being shot in the stomach by another officer, Page fatally shot himself in the head.” [via Wikipedia]

Below I’ve gathered together some of the reactions to the tragic Oak Creek shooting, presented without comment. Feel free to add your own links, or leave comments below. (Respecting our comments policy, of course!)

An American Tragedy, by Naunihal Singh:

The media has treated the shootings in Oak Creek very differently from those that happened just two weeks earlier in Aurora… Sadly, the media has ignored the universal elements of this story, distracted perhaps by the unfamiliar names and thick accents of the victims’ families. They present a narrative more reassuring to their viewers, one which rarely uses the word terrorism and which makes it clear that you have little to worry about if you’re not Sikh or Muslim.

Top Ten differences between White Terrorists and Others, by Juan Cole:

2. White terrorists are “troubled loners.” Other terrorists are always suspected of being part of a global plot, even when they are obviously troubled loners.

Special Circumstances vs. The Dorthraki

Rex’s last post reminds me that I’ve been meaning to write about one of the most fascinating science fiction worlds I’ve come across in a long time. I’m talking about The Culture novels of Iain M. Banks, which I want to compare with George R.R. Martin’s Game of Thrones [the TV show – I’ve not read the books].

I want to talk about the role of ethnic difference in narrative, but since Rex brought up the issue of bodies, let me first note that one of the interesting things about The Culture is that unlike the many other “highly advanced alien species” discussed by Rex in his post, bodies are very important to The Culture. In this post-singularity world people can back themselves up or choose to live entirely virtual lives, but most choose to have bodies anyway. These bodies are enhanced, to be sure: they have neural laces to tie them to the co-evolved artificial Minds which run their space ships, and they have extra glands which give them whatever drugs they might like at a mere thought, but they are still bodies. Over their long lifespans they can choose to be male or female at will, and many go through several changes over a lifetime. The Minds too can take on human avatars, and the nature of these avatars is an important reflection of their personalities, although we are frequently reminded that they are not human. For instance, they can eat and defecate, but they don’t have to and the food which is passed through their bodies is still edible since it hasn’t really been digested. We are even told that some humans like to eat avatar-digested food. But then who understands humans? Continue reading

Cinco de Mayo is the new St. Patrick’s Day

And Mexicans are the new Irish.

Growing up in Texas I always had trouble keeping Cinco de Mayo and Diez y Seis straight. To my mind the former was in commemoration of a colonial event, the defeat of Spain maybe, and the latter marked the date of the Mexican Revolution. Or maybe I had it backwards? And while Diez y Seis might warrant a baile folklorico demonstration or a performance from the high school mariachi band in the state capital, Cinco de Mayo was marked by the ritual of going out to a Mexican restaurant for dinner.

In college in Florida the Caribbean immigrants and the children of immigrants I came to know were just learning about Mexican American culture, so the observation of Cinco de Mayo was novel to them. All we needed was an excuse to drink margaritas and we were on our way! By the time I got to North Carolina for grad school the holiday had gone mainstream. I couldn’t help but be a little bit proud, like when salsa surpassed ketchup as America’s number one condiment. Imagine my joy when I learned that the 2005 annual meeting of SANA and CASCA would be held at UADY in Merida over Cinco de Mayo. AMAZEBALLS!! Spend Cinco de Mayo in Mexico? Hells to the yeah!

It turns out Mexicans don’t really give a shit about Cinco de Mayo. Continue reading

Everybody’s Linning

Jeremy Lin is the latest basketball sensation. Sports usually isn’t my beat, but I trust Nate Silver to do the statistics and he says Jeremy Lin’s recent success is no fluke. What I find interesting is how everyone seems to want to claim a piece of Lin: nerds, Christians, asian-Americans, Chinese, Taiwanese, etc. Let’s take these one by one, starting with nerds.

The New Yorker describes how Lin, a Harvard graduate, and Landry Fields “a Knicks guard from Stanford, have developed a handshake: put on spectacles, flip through a textbook—Organic Team Chemistry, we presume—take the glasses off, and stick ‘em in your pocket.” You can see this ritual here:

It used to be, before the GI Bill radically changed American higher education after World War Two, that it was common for the top athletes to come from the top schools. Now I believe it is more the exception than the rule. Continue reading

Racial Differences In Skin-Colour as Recorded By The Colour Top

The “Bauhaus Optischer Farbmischer” (via Mabak)

The title of this post comes from a 1930 article in Man which discusses the superiority of such tops over various other ways to measure skin color, such as Broca’s skin color charts. While I knew anthropologists had used Broca’s charts, I don’t recall reading about the use of color tops, which was apparently quite common. The tops used were actually by Milton Bradley, but as best I can tell they were quite similar to the Bauhaus design pictured above. [Can anyone find a picture of the actual Milton Bradely tops?]

The colour top is a device made by the Milton Bradley Company, of Spring- field, Mass., U.S.A., a firm which manufactures kindergarten supplies. It is, primarily intended for teaching children the principles of colour blending. The first investigator to use it for recording skin-colour was Davenport, who employed it in his study of the heredity of skin-colour in Negro-White crosses in Jamaica (1913). The principle is one with which we were all familiar in our childhood. The apparatus consists of a small top, of the disc variety, spun by means of a wooden spindle kept in place by a nut. On this basal disc, which is of cardboard, are placed paper discs of various colours. When the top is spun the colours blend… The proportion of each colour which goes to the make-up of this composite surface can be varied at will, by merely moving the discs round upon the spindle… By suitable adjustment of these four discs, the spinning surface can be made to reproduce,with a considerable degree of exactitude, the colour of human skin of all shades and gradations that may be met with.

Be warned, however,

The judgment must always be made while the top is rotating at full speed. Even slight slackening of speed renders matching difficult and the records unreliable.

I learned of the use of these tops from an interview with Michael Keevak, author of Becoming Yellow: A Short History of Racial Thinking. It sounds like another interesting book from the man who wrote The Pretended Asian: George Psalmanazar’s Eighteenth-Century Formosan Hoax, which I blogged about back in 2006.

How Avatars Work In the Real World

In Hollywood, caucasian men adopt avatars to become one with indigenous aliens, but that’s not how the racial politics of avatars work in the real world. Rural schools in South Korea are getting robot English teachers and, well, read on:

The robots, which display an avatar face of a Caucasian woman, are controlled remotely by teachers of English in the Philippines — who can see and hear the children via a remote control system.

Cameras detect the Filipino teachers’ facial expressions and instantly reflect them on the avatar’s face, said Sagong Seong-Dae, a senior scientist at KIST.

“Well-educated, experienced Filipino teachers are far cheaper than their counterparts elsewhere, including South Korea,” he told AFP.

It would be a lot easier to just have a direct video feed of their Filipino teachers, but why do that when the magic of virtual reality can give you a white teacher? And unlike real white teachers “they won’t complain about health insurance, sick leave and severance package, or leave in three months for a better-paying job in Japan.”

(Via Roy Berman on Twitter)

Ethnogenesis: A Radical Constructionist Case

I just finished James Scott’s 2009 book, The Art of Not Being Governed: An Anarchist History of Upland Southeast Asia, and I thought I’d take a couple of minutes to introduce the book to those not familiar with it. I quite enjoyed his last book, Seeing Like a State, which I wrote about back in 2007, and this book picks up where that book left off. Whereas Seeing Like a State discussed the strategies by which states exert bureaucratic control over unruly populations, The Art of Not Being Governed looks instead at the strategies people adopt to resist centralized state control. [The title of this post comes from one of the chapters in the book.]

His focus is on Southeast Asia, specifically a region he calls “Zomia” which, to quote Martin Lewis:

denotes the mountainous areas of mainland Southeast Asia, along with adjacent parts of India and China, that have historically resisted incorporation into the states centered in the lowland basins of the larger region.

In chapter after chapter he lays out his argument, showing how virtually every aspect of Zomia hill society exists as a means of resisting state authority: If states like the flat plains, people move to the hills to avoid the state. If states like cultivating rice because it concentrates much needed manpower where it can easily be tapped, people adopt shifting cultivation for the very same reason. If states employ writing as a way of keeping track of who’s who, people ditch their books and rely upon easily modified oral genealogies instead. If states like organized religion, people engage in heterodox traditions that defy centralized control. And, perhaps most strikingly, if the state wishes to impose a shared ethnic identity upon its subjects, people choose “tribal” identities as a way of avoiding such ethnic ties.

Indigenes or citizens in Papua New Guinea?

Despite the fact that it is my area of expertise, I do not normally comment on the mining and petroleum scene in Papua New Guinea. Despite having studied the industry for more than a decade, I will never know as much as my ‘informants’ — the people actually living with mines and oil projects. This is particularly true for current affairs, when the ‘real story’ of what happens on the ground is often much different from reports circulated by the press. Nevertheless, I do feel compelled to say something about the shameful events that have recently taken place in country — and the way they are being received by the anthropological community and others.

The government of Papua New Guinea recently amended the country’s Environment Act to make it illegal to appeal permitting decisions made by the minister. The immediate reason for this change is clear — the national government relies on large, internationally-financed resource developments to fund it budget. The Ramu NiCo mine in Madang province, majority-owned and operated by a Chinese firm, is planning to dispose of tailings by dumping them into the sea — a move that many, many people in Madang oppose. When anti-mining groups got an injunction against the mine, the government responded by making it illegal to oppose their decision to let the mine go ahead.

The issue is actually more general than this. Landowner groups and others who oppose mining and petroleum developments often challenge environmental permitting in order to pressure or halt operations. Mining leases are rarely reviewed and renewal is largely a matter of course, but water use permits (for toilets on site, for instance) more regularly come up for renewal — and miners need toilets. The Ramu case is just one instance of a much broader tactic used by people opposed to mining.

The big picture is that Papua New Guinea is torn — between politicians in Moresby who are want to use mining revenue to enrich and develop the nation, and grassroots Papua New Guineans who don’t see why they should suffer so others can gain the benefits of mining revenue. When Papua New Guinea became independent in 1975, the country inherited the benevolent paternalism and technocratic confidence of its colonizers — the first generation of educated Papua New Guineans were going to lead the country forward and help develop the grassroots in the name of national progress. Now the worm has turned and Papua New Guinea’s leadership seems to see Papua New Guineans as ungrateful and stubborn — after a peaceful protest organized by Transparency International outside parliament, the prime minister called those who participated “satanic and mentally insane”.

In an article I am working on right now, I examine newspaper coverage of these issues in order to understand contemporary transformations of nationalism in Papua New Guinea. My conclusion – which at this rate will not be published until my kids head off to college! — is that Papua New Guinea is torn between two different idioms to express this conflict between grassroots and the political elite. Within the country, the language used is that of the nation: ironically, the nation-making project of the independence period was so successful that many Papua New Guineans now see themselves as uniting against the state in the name of national unity. Externally, however, the language used to describe these conflicts is that of indigeneity. Coverage of recent events by a UN-sponsored website, for instance, describe the problem as one in which “indigenous people lose out on land rights”.

What I do not say in the article — since it is all scholarly and everything — is how incredibly disappointed I am in the government of Papua New Guinea. Democracy is not fun or easy, and the paralysis induced by lawsuits can be a huge pain, but the solution to these problems is not and can never be removing people’s rights to participate in the processes that will affect their lives. This is particularly true in the case of Ramu, where environmental concerns are justified and deeply felt, not simply cynically used as tactics in a political process. Transparency, accountability, and participation are all incredibly stupid and ridiculously ineffective ways to run a government — but we chose them because democracies put people’s rights ahead of convenience or practicality.

Additionally, I am very uncomfortable with labelling this as a conflict featuring ‘indigenous’ people — despite the fact that I know appealing to international forces using the idiom of indigeneity is often yields useful leverage in political contests like the one at Ramu. But in fact Papua New Guineans are indigenous only in the (often oppressive) eco-authentic sense: they are brown, they have ‘exotic’ languages and cultures, and they live in a place full of endangered species of animals. They are not, however, ‘indigenous’ in the much more important political-emancipatory sense: there is (and was) no real settler colonialism in Papua New Guinea, no large scale expropriation of land, and not even an ethnic majority to oppress minority groups. Despite how easy it is for outsiders to shoe horn Papua New Guinea into popular and easy paradigms of indigenous struggle, such a construal of Papua New Guinea’s story does not do the country justice.

Eco-authentic definitions of indigeneity perpetuate stereotypes of Papua New Guinea as savage backward by giving them a positive moral valuation. They obscure from sight the large number of educated Papua New Guineans, and they stigmatize Papua New Guineans’ decisions to take part in urban, cash-based economies as an abandonment of precious indigenous heritage.

Most importantly, however, these idioms tempt Papua New Guineans to give up on their country and its government. With corruption in the civil servant rampant and elections in Papua New Guinea too-often a mere shadow of genuine democracy (there is video footage of political henchmen unapologetically — and literally — stuffing ballot boxes), it is easy these days for Papua New Guineans to opt out, to declare the government an illegitimate opponent of the grassroots rather than to hold it to account as the voice of the people. Perhaps they do not need the ‘indigenous alternative’s’ help in abandoning any conception of state legitimacy. But I think Papua New Guinea loses something important when it gives up on its dreams of independence and self-government. Even though it may require people to dig deep, I would urge Papua New Guineans not to give up on the light at the end of the tunnel, and to insist that they are citizens, not indigenes, of Papua New Guinea.

Whiteness as Ethnicity in Arizona’s New Racial Order

Along with other recent wackiness, Arizona’s state legislature passed a law, HB 2281, which aims to prevent or limit the teaching of ethnic studies.

HB 2281:

Prohibits a school district or charter school from including in its program of instruction any courses or classes that:

- Promote the overthrow of the United States government.

- Promote resentment toward a race or class of people.

- Are designed primarily for pupils of a particular ethnic group.

- Advocate ethnic solidarity instead of the treatment of pupils as individuals.

This is not a new development — I first wrote about this on Savage Minds almost a year ago, although I figured it was the kind of right-wing looniness that makes great theater but never gets through the legislative process. Continue reading

On (Un)seeing

One of the films I neglected to mention in my last post on the Taiwan Int’l Ethnographic Film Festival TIEFF was Patrasche, A Dog Of Flanders – Made in Japan. Because it is a feature length film, I didn’t list it as a teaching film, although I could easily see it being used in a class on popular culture. The film is a humorous exploration of how the book “A Dog of Flanders” which is very popular in the US, UK, and Japan has been adapted and received in each of those countries, as well as in the place the story is set: Flanders. The basis for several films and a Japanese anime TV show, this book has never caught on in Flanders, although there have been some belated efforts by Belgians to cash in on the story’s popularity with Japanese tourists.

The film states several times that one reason the story of failed to become popular in Belgium is that the residents of Flanders don’t see Flanders when they read the book or watch the films, or the TV show. Rather, what they see is Holland. This isn’t surprising, since visiting filmmakers will find little pastoral beauty in modern day industrial Flanders, and Holland is just a twenty minute drive away. But while foreigners might not be able to tell the subtle differences in dress, or even the color of stones used in the streets and buildings, the people who live there are very, very aware.

I probably would not have thought twice about this, except I have also been reading China Mieville’s surreal crime-story, The City & The City. Here is how the Guardian describes the book’s central premise:

the city of Beszel exists in the same space as the city of Ul Qoma. Citizens of each city can dimly make out the other, but are forbidden on pain of severe penalties (administered by a supreme authority known simply as Breach) to notice it. They have learned by habit to “unsee”. The cities have different airports, international dialling codes, internet links. Cars navigate instinctively around one another; police officers cooperate but are not allowed to stop or investigate crimes committed in the other city.

The novel takes a trick or two from my favorite writer, Bruno Schulz, imagining twin cities occupying the same physical space. A situation reminiscent of another enjoyable film from the TIEFF festival, Jerusalem(s), which follows Jewish, Muslim, and Christian tour guides around Jerusalem. Constantly cutting to the numerous surveillance cameras which are also watching. But the book captures something which is not just true of divided cities like Jerusalem or cold-war Berlin, it is also of Flanders. In order to “unsee” someone from Ul Qoma, the residents of Beszel must be alert to subtle signs of dress and manner, just as the residents of Flanders would never be mistaken for Dutch.

I believe manner of seeing is something we don’t just learn, it is something we cultivate. We are proud of our ability to (un)see differences. Every once in a while I meet a Taiwanese, usually someone who lives abroad, or has travelled widely. They peg me for Jewish, but don’t want to broach the topic directly, so the usually ask me if I might not be French. When I insist that I am not, however, they usually garner up the courage to pursue the question until they’ve established that they were correct to begin with. I also know my friends of mixed ancestry (which, of course, is all of us – but you know what I mean) can cause tremendous significant discomfort in random strangers, simply because they are difficult to peg. A Japanese-Afghan friend gets asked: “What are you?” by total strangers on the subway. Once they know “what” she is, they can go back to unseeing her.

UPDATE: Some slight corrections made.

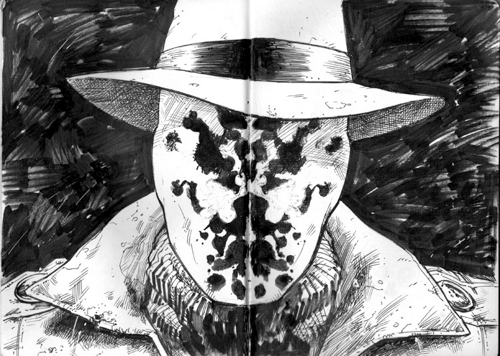

Rorschach Test

The Henry Louis Gates Jr. affair (“gatesgate”) seems to be some kind of national rorschach test. Gates has portrayed it “as a modern lesson in racism and the criminal justice system.” Or as put more eloquently by Stanley Fish: “The message was unmistakable: What was a black man doing living in a place like this?” (Fish also ties this question to the media frenzy over Obama’s birth certificate.) But others have seen it as a class issue: “He isn’t outraged because he feels he was the victim of racial profiling by the police… He’s outraged because he was the victim of class profiling.” Rush Limbaugh takes a similar approach, as does the National Review. Or even (albeit much less convincingly) gender: “would any of this have happened if the major players had been women?” (Um, don’t you watch COPS?)

But it doesn’t stop with class/race/gender. It is also an issue of civil liberties: “the thing about all of this that creeps me out the most is that so many people are willing to defend this officer who…arrested a guy because he didn’t like his attitude.” Or, “professionalism“: “By telling Gates to come outside, Crowley establishes that he has lost all semblance of professionalism. It has now become personal and he wants to create a violation of 272/53 [the statute authorizing prosecutions for disorderly conduct].”

As mentioned above, most mainstream right-wing pundits seem to be taking the “elitist” tact on this case, but some go even further, arguing that it is reverse-racism: “All he has is a collection of prejudices about the group to which the officer belonged: white police officers. And based on that collection of prejudices, Gates leapt to a conclusion — this police officer is a racist.” Others on the right seem eager to reduce the story to a personal narrative, emphasizing how the cop, “James Crowley has taught a class about racial profiling for five years…”

I don’t get the impression that it is a case which has attracted quite as much attention outside the United States, certainly not here in Taiwan, but I could be wrong. I’d be very curious to hear from our readers how this incident has been portrayed elsewhere.

(Thanks to Carole McGranahan for pointing out the “personal narrative” angle.)

UPDATE: Charles Blow has more on the different experiences of race in the United States and how they affect how one is likely to interpret this story:

Whether one thinks race was a factor in this arrest may depend largely on the prism through which the conflicting accounts are viewed. For many black men, it’s through a prism stained by the fact that a negative, sometimes racially charged, encounter with a policeman is a far-too-common rite of passage.

UPDATE: Another “professional” frame, this one saying that shooting someone for asserting their constitutional rights (instead of obeying immediately) is, in fact, what one should expect from a well-trained police officer:

He is instead concerned with protecting his mortal hide from having holes placed in it where God did not intend. And you, if in asserting your constitutional right to be free from unlawful search and seizure fail to do as the officer asks, run the risk of having such holes placed in your own.

UPDATE: Over at anthropoliteia, a blog devoted to the anthropology of policing, Jeff Martin says this is a teachable moment:

To focus discussion of the event onto the cultural dynamics by which larger issues are made relevant to social action, we can usefully borrow Marshall Sahlins’ concept of the “symbolic relay,” i.e. symbols which are deployed to “endow the opposing local parties with collective identities and the opposing collectives with local or interpersonal sentiments.

Whereas Radly Balko says “If there’s a teachable moment to extract from Gates’ arrest, it’s that arrest powers should be limited to actual crimes.” And Tenured Radical says that what he learned living in an integrated neighborhood “is that white people put black people in danger every day.” Meanwhile, the police released a recording of the phone call to the police placed by the white neighbor.

Why is Alito neutral, and not Sotomayor?

A brilliant account of how America thinks about ethnic difference by Stephen Colbert:

Yes, [Samuel Alito] takes his life experiences into account, but he does it neutrally! So why is he neutral, and not Sotomayor? It’s because Alito is white.

Via Sociological Images, where you can read a full transcript of the segment.