I’ve seen some proposals for resistance to the corporatization of the university being circulated among anthro colleagues recently. These range from ideas about boycotting the peer review process of for-profit academic journals, to the Cost of Knowledge campaign, to the widespread action by academics to free their work from paywalls in the PDF Tribute in response to the tragic death of Aaron Schwartz, to the call not to pay (as many) conference fees by minimizing/strategizing conference attendance. The other day some colleagues of mine also suggested subversive, pro forma mass-co-authorship of articles in response to the pressure of quantitative publication norms as a criterion for good scholarship.

Tag Archives: experiments

Fly-on-the-wall or Troll?

Thanks for letting me guest blog on Savage Minds this month! I’ll wrap up with some meta analysis about being an activist/anthropologist/blogger type.

I’m not a regular commenter on any websites, but sometimes I read long comment threads on controversial posts, spending enough time that I go into a kind of trance until something snaps me out of it and I’m disgusted by my own voyeurism. From these forays I’ve learned that people are quick to accuse commenters with unfamiliar screen names and unpopular opinions of being trolls, meaning they are only there to elicit a reaction. Writers can also troll for pageviews. (I don’t study online sociality or new media, so sorry if this sounds like The Internet 101: Beyond AOL.) Controversial posts often go up with the intention of eliciting reactions to raise pageviews, for monetary gain or fame or to raise awareness.

For the most part, I’m an outsider to that game. I think of my own blog as an archive of knowledge, there for the Googling, rather than part of a click-oriented news cycle. A “trending” category on my blog would probably just be an image of a skeleton covered in cobwebs. I reliably get a “great writing Doni!” comment from, you guessed it, Mom, but most people who look at my blog don’t leave comments. I do, however, monitor pageviews out of curiosity.

Bicycling and Ethnographic Access

Savage Minds welcomes guest blogger Adonia Lugo.

I was thinking about how to start talking about bicycling and anthropology on Savage Minds when I saw this post on Gizmodo about bicycling through lower Manhattan during the hurricane that inundated the east coast of the U.S. earlier this week. This is what Casey Neistat saw while he was exploring via bike during flooding on Monday night:

This footage is exciting, and heartwrenching. Seeing New York City in a crisis is scary, even for those of us who don’t live there. And in light of the longstanding attempts to deny climate change, water lapping against the iconic urban density of Manhattan says something frightening, to me at least. But another statement the video makes is that a bike can take you places other forms of mobility sometimes can’t.

LOL Anthropology

Recently I’ve been rethinking my attitude towards popular trends in anthropological theory. You know what I’m talking about… that sudden realization that a whole bunch of anthropologists seem to be engaged with a theoretical framework, scholar, or empirical subject matter that seems to have come out of the blue while you weren’t paying attention. Lacan, Agamben, affect, transnational flows… whatnot. In the past I used to share Marshall Sahlins sense that these were but passing fads and that long-established anthropological traditions had already said many of the same things if we just knew where to look for it. Now I’m not so sure.

Lately I’ve been thinking that there is something productive about playing with the latest lingo. The important word is “play.” Just like internet memes, trying to fit your research or ideas into a new meme gives one a chance to see the material afresh. Hell, it can simply make it fun again, like remixing Gangnam Style with Star Trek the Next Generation, or removing all the music and adding sound effects, or perhaps even just singing it as an acoustic set.

memos on ethnographic practice

I’m DJ Hatfield, one of the guest bloggers for this month on savage minds. When thinking about possible themes for my blog, I just happened to be reading one of my favorite books on writing, Calvino’s Six memos for the next millennium. Originally, these memos were planned lectures about the values of good writing that Calvino was to give at Harvard; he died before giving the lectures and, indeed, before finishing the work. It might surprise several people who read savage minds that Calvino’s six memos (well, the five that he finished!) are what I turn to when I want to think about my practice as an ethnographic writer. And I think that there is much virtue in the structure of Calvino’s little book: the task he set before himself in 1984 was to describe particular qualities that writing should have if it were to meet the challenges of the next millennium–something that might have been envisioned by the editors of writing culture if a peculiar parricidal impulse hadn’t motivated that work. Of course, as a graduate student, the project of writing culture fit my bill. Now that I have a book and a few articles behind me, it’s Calvino’s project that incites my questions about what we do as ethnographers. What are the values that we would think of as central to the practice, what Macintyre in After Virtue called the “internal goods”–those values that we cultivate as we do our work in the field and out? I’d like to start a conversation on this question. As I am not sure whether what I will discuss will be values in the sense of the ends of our practices or in the sense of what orients them, I’ll leave you to give your preliminary suggestions. My postings on some of these values, plus some discussion of recent work, will appear throughout the month of October. My first internal good: friendship

Decentering Writing

[The post below was contributed by guest blogger Deepa S. Reddy, and is part of a series on the relationship between academic precarity and the production of ethnography, introduced here. Read Deepa’s previous posts: post 1 — post 2 — post3]

Note: updated on 7/26/2012 for clarity.

For this final post in our series, I find myself returning to Carole McGranahan’s post from some weeks ago, going through her very useful 9-point schema to describe what makes things ethnographic these days—realizing that whatever the circumstances of ethnographic production, whatever our definitions of ethnography might be, they always presume the centrality of writing. And that is writing in a particular mould, one that satisfies most, if not all, of the criteria enumerated in McGranahan’s post. Specialized, often lengthy, mono-graphs or variants thereof.

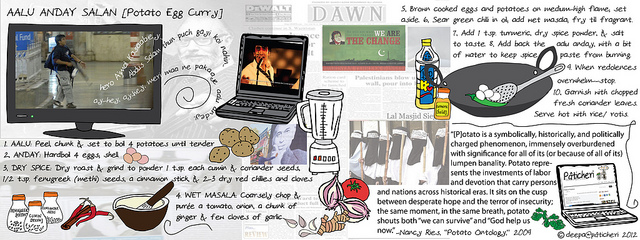

Recipe for Pakistani-style Political Potatoes

Recipe for Pakistani-style Political Potatoes

[Click on the image for a more readable higher-res version]

Part of me wants to say: But of course, how could it be otherwise? The other part, perhaps handicapped by my present need to cobble together a professional identity while remaking myself in an almost completely new cultural landscape—and finding precious little time to devote to writing, is wondering about ethnographic end-products, and the centrality of conventional writing to the ethnographic enterprise. In this post, therefore, I’d like to think through the prospect of decentering writing [fully aware that writing can’t ever be entirely displaced; that there is an awkwardness to the idea, reflected in this post’s two-ing title]. Continue reading

Social Reading Logs

How do you jumpstart the life of the mind when you aren’t physically located in one of those rare places bubbling over with Mind? In an earlier post I discussed using Wunderkit to increase reading capacity and ‘surveil’ colleagues as one way to get something going, intellectually speaking. Since writing that post my thought have changes a bit and I wanted to talk in more detail about my thinking behind my social network use lately. First, although ‘surveil’ sounds good and is probably accurate, the branding is all wrong and it doesn’t really capture what I am trying to get at: a vital and productive community of ‘social reading logs’. Second, Wunderkit has not shaped up into a platform that can accommodate what I’m looking for (at least not so far).

Surveilling your colleagues for fun and profit with Wunderkit

Facebook, Academia.edu, OpenAnthropology.org, ResearchGate — in a world full of social networking sites for social scientists, what is the point of registering for one more? In the past month or so I’ve had very good results using Wunderkit to surveil both my students and myself, and although the system is far from perfect, I think its useful enough to blog about for others who are interested.

My Journey Through Innerspace

This past Thursday I spent the morning floating in a sensory deprivation tank. I saw it on sale through Groupon and I thought, why not? An interesting experience, it was very relaxing and left me with a kind of euphoria which permeated my being for another two hours after the event. It put me in a gentle, mellow mood for the rest of the day.

I found out about this place by following a link from an io9 post to a website called Float Finder, which puts people in touch with their local sensory deprivation center and also seems to be a hub for a whole tank-subculture. The io9 piece is really worth a read too, especially the bit on sensory deprivation pioneer John C. Lilly, a man who took intramuscular LSD until he discovered he could speak to dolphins.

Or as io9 puts it–

Calling John C. Lilly eccentric would be akin to calling the Beatles a popular band – somehow “eccentric” just doesn’t do the man justice.

How I Would Use Twitter To Take Over Anthropology, If That Was What I Wanted To Do

I am not a huge fan of Twitter but I do have a presence (I’m r3x0r (with a three and a zero, not an O) if you want to follow me) and I try to be interested in the technology even if I am a late adopter. However about two seconds ago I realized how I could use Twitter to become powerful and influential in anthropology, then decided that that wasn’t something that I really wanted to do, and then decided I hadn’t blogged anything lately so I might as well blog this even — especially! — because I wasn’t going to do it. Maybe someone has already written a paper about this (or a similar strategy in a different content space) would work. In which case this is an obvious idea and you can feel free to harangue me in the comments.

Some of my most retweeted posts are links to articles and books that I like. I tweet about them because I see Twitter, like a lot of the Internet, as a place to discover new scholarly material which has been vetted and filtered by people whose taste I trust. Why, for instance, should I page through old tables of contents of Leonarda when I can just get a recommendation directly from Jenny Cool? In particular, I tweet as a way to remind myself (who I follow and archive) of articles from newly published journals that I would be interested in reading. Of course, I’m also interested in letting my friends know what I am reading, building scholarly community, and so forth.

If you increased volume a lot — but not to the level of some gossip twitterers — and adopted a more cynical attitude to posting it would be relatively easy to become a definitive maker of public opinion just by sustained gumption. All of the key features of academic faddism are accentuated by Twitter: the focus on speed, the ability to dredge up and lionize obscure sources and, best of all, a media cycle so short that people tweet articles rather than actually read them. In a world of no competition, cynically tweeting the newest latest slowly starts creating a definitive voice in the public sphere — indeed, the public sphere itself — just because there is no one else. In a world of heavy competition other factors would lead to dominance, including outlasting other tweeters, ‘platform’ (already being famous), and of course the quality of your ability to filter content down to the choice nuggets.

After a while I think it would be possible to start streaming tweets about new and hip content based purely on reading tables of contents rather than the articles themselves — since after all no one is reading the whole articles anyway. The result would be something like that Stanislaw Lem short story where the the guy dresses up as a robot to investigate the world of evil robots only to find out that it is populated entirely by people dressed up as robots trying to hide that fact from each other: one would have the constant sense that there was a consensus about what was new and important that everyone else was reading or invested in. If this was the mining industry — where accurate fast news and analysis sell at a premium — we could pursue a ‘premium pricing strategy’ and sell subscriptions to an email alerting system that would send you up-to-the-minute lists of articles that everyone but you already knew about.

The sad thing about this strategy is that anthropology feels itself to be so fractured that I think people — especially non-tenured people — are desperate for some sort of shared common ground that they could latch on to as ‘what anthropologists actually know and talk about’. So much of contemporary work these days consists of pieces so short and without a ‘boring’ literature review that you must carefully read between the lines to understand what went on in the room where the conference on global assemblages was held. Or… perhaps this is not a new thing?

If you can find a way to turn this cynical plan for self aggrandizement into a way of knitting the diverse communities of anthropology into a coherence whole with a well-defined, democratically defined canon please let me know in the comments below.

Why I <3 Anthropology

I love anthropology — cultural anthropology, my subfield of the discipline — because it is the most human of the human sciences: the one that is the most about people. The one which thinks you can learn about how people live their lives by watching how they live their lives — not by building models of them, or having them live small parts of it laboratories. In order to understand people we study people, and is willing to embrace all the challenges this entails.

I love anthropology because it is the discipline that takes seriously the idea that our common humanity with those we study is a boon and a strength, not an impediment that distort objective judgment. It works with and works through the fact that we can be powerfully changed by our research, and that this change is a strength. I love the fact that we stick with the project of ethnography despite the fact that it is aa project of telling the stories of others, an entitlement to be earned, not a right to representative authority that can be assumed.

The other day for a project I read the tables of contents for every issue of American Anthropologist from 1900 to 1960. One of the articles I came across was called “Columns of Infamy”. I love that.

I love anthropology’s willingness to compare anything to anything else and to study anything under the sun. If people have done it — or thought about doing it — it’s not off-limits. And I love that fact that we can compare people who think they were abducted by aliens in Arkansas in the 90s with ascent to heaven narratives from Sumer written thousands of years earlier.

I love our regional, middle-range expertise: where people call soda coke and where they call it pop, how far south the cultural syndrome of the vision quest extends, and how lycra got marketed to the women’s movement in the 1960s.

But I also love our willingness to completely throw the middle range to the wind, our ability to start with a local taboo against eating bandicoots and ascending to universal theories of human anxieties about embodiment. We drive the philologists mad, which is ok with me.

I love anthropology’s protean genres — our ability to articulate with public health, philosophy, english literature, and military intelligence. When we say we will study anything, we are talking just as much about adjacent disciplines — and they are all adjacent — as we are people out in the world. At the same time, when locked into a four-field configuration like an X-Wing with foils extended into attack position, we really do have some answers to some important questions about what it means to be human. And if the physical anthropologists want to go talk to physicists about strontium isotope analysis, who can blame us for having lunch with someone who studies French literature?

Anthropologists can find anything interesting, and I love that about the discipline. You meet someone and ask what they are studying and they say “rodeos as cultural performance” and heads start nodding. You drive past a garage sale and stop the car in the middle of the street and say “they’re… selling… old lampshades…” And yet at the same time we are incredibly jaded. More fears in the Andes that aid workers are using syringes to suck the fat out of people’s bodies as they sleep? Well that’s not very surprisng, is it?

I love anthropology’s ability to take people’s beliefs incredibly seriously one minute and then to totally ignore them in the next. That’s not witchraft, you fool, that’s your anxiety about your social organization. Except, no wait, what if there are witches? Biology? You think that stuff at the bottom of the microscope is ‘reality’? Have you read Rheinberger’s book on the history of the ‘discovery’ of protein synthesis?!?! Except, actually, this whole ‘cooperative breeding’ thing does knit together what we know about primate behavior, evolution, and the human capacity for culture. Hmmm….

I love that fact that anthropologists refuse to give up on the fact that a two hundred page book has more insight and value than ten twenty page articles. I love the fact that we are willing to grasp the nettle of style instead of pretending it isn’t an issue. I love that fact that we believe our subjectivities add value to our scholarly work, rather than contaminating it.

Above all I love how anthropology, a science of the human, articulates with our lives: we study kinship, and raise children. We read about enculturation, and we teach students. We analyze power and we try to create a democratic, just world. Our discipline is connected, intimately and irrevocably, to our whole persons — and that’s what I love about it most of all.

This Valentine’s Day, a love letter to anthropology

I have a collaborative project that I would like to float out to the anthropology blogosphere on this Valentine’s Day: a love letter to our discipline

This won’t work for several reasons: First, because of my position on the earth, it is probably not Valentine’s Day where you are. Second, there is a strong chance that I’m opening the flood gates for endless cynical, bodice-ripping parodies. But I’d still like to give it a shot.

This idea is simple: in the next seven days, for a few thousand words, somewhere public on the Internet, write about why you like anthropology. Then we’ll make the guys at Neuroanthropology do a round up.

Back in the good old days of last month, when #AAAfail was on everyone’s lips, I suggested that we ask anthropology bloggers to provide ‘creeds’ or statements of belief about what anthropology was or should be. I let the idea drop because it seemed sort of dogmatic and unfun to list what you think The Deal is with anthropology. I’m hoping that the Valentine’s Day format will help accomplish a similar thing, but with a little bit of fun thrown in.

So let’s see whether anyone wants to take up the V-Day challenge in the next week and talk about what what anthropology is and why they like — nay, even love — it. Get cracking!

Ethnography as a solution to #AAAfail

One of the things #AAAfail has revealed is not just wide divisions within the anthropological community about what anthropology is — I think we all knew those were there — but also wide division about what the terms to evaluate those divisions mean. Especially the term ‘science’: does this mean a general belief ‘in reality’ and ‘a broad commitment to empiricism’ or something more specific like ‘deductive research methodologies, an attempt to minimize the subjectivity of the researcher, extremely specific genre choices about conveying research results’ and so forth. One of the biggest problems, in other words, is that we have no ethnography of what anthropologists believe about their discipline.

What do most anthropologists think anthropology does? What do the terms they use to evaluate it mean to them? To the best of my knowledge, we simply have no answer to this question beyond our impressions that ‘cultural anthropologists are taking over’. As a scientist (in the general sense of the term) my training tells me the first step in resolving the issues raised by #AAAfail is to get some data on the phenomena we want to study.

Swarm

A highlight of the recent AAA conference in New Orleans was a visit to one of the three art galleries participating in Swarm: Multispecies Salon 3, one of the new “inno-vent” functions spun off from the usual conference proceedings. There was a “Multispecies Anthropology” panel at the conference itself, but sadly it was timed to overlap with the very panel I was participating in. As a multimedia art installation Swarm was highly stimulating and a lot of fun too, I would have loved to see it tied more directly to contemporary cultural anthropology and theory. Fortunately I can turn to the journal Cultural Anthropology Vol. 25, Issue 4 (2010), a special theme issue edited by some of the co-curators of Swarm that explores the intersections of bioart and anthropology, humans and non-human species, science and nature.

Saturday evening, after the SANA business meeting and a catfish po-boy, I slinked back to my cheap hotel for a change of clothes and to get the address of The Ironworks studio on Piety Street. It turns out hailing a cab in New Orleans on a Saturday night can take awhile, especially when you’re in the CBD. And when I did get a cabbie, he confessed to not knowing where Piety Street was and his sole map seemed to be a tourist brochure which only listed major intersections. (“Here put these on,” and he gave me his reading glasses as if this would help.) I bargained that waiting to catch another cab would take longer than navigating with a lost cabbie and so we set sail on the streets of New Orleans.

After the confusion, a train, and about six blocks of streets without names we arrived. The Ironworks was an ideal setting for this experiment in art and anthropology. At the end of a city neighborhood, under the comforting glow of the street lamps, the building suggested a past life as a warehouse or place of light industry. Inside a high fence folks gathered around a keg of beer or perched on picnic tables on the edge of a interior yard whose distance brought darkness and a sense of privacy. This is where the robots roamed, clacking and blinking.

Inside I soon found my friends, alums from my alma mater New College – many of us became professional anthropologists – had agreed to swarm the Swarm. Much to my surprise there were even some undergrads who spotted me right away by my tattoo of the school logo and a fellow from my class who became a criminal lawyer and now lived right down the street. Also there were tamales. And a band of noise musicians. It was good crowd to be in, a mix of ages, anthropologists and artists.

Collage for NOLA: Ruin

Walter Benjamin, “Surrealism” in Reflections

[Andre Breton] was the first to perceive the revolutionary energies that appear in the “outmoded,” in the first iron constructions, the first factory buildings, the earliest photos, the objects that have begun to be extinct, grand pianos, the dresses of five years ago, fashionable restaurants when the vogue has begun to ebb from them.

…

They bring the immense forces of “atmosphere” concealed in these things to the point of explosion. What form do you suppose a life would take that was determined at the decisive moment precisely by the street song last on everyone’s lips?

Suan Buck-Morss, The Dialectics of Seeing

More generally, throughout [Benjamin’s Arcades Project], the image of the “ruin,” as emblem not only of the transitoriness and fragility of capitalist culture, but also its destructiveness, is pronounced.

Six Flags New Orleans, October 2010. Via.

Kathleen Steward, A Space on the Side of the Road

A rambling rose vine entwined around a crumbling chimney remembers an old family farm, the dramatic fire in which the place was lost, and the utopic potential clinging to the traces of history. Objects that have decayed into fragments and traces draw together a transient past with the very desire to remember. Concrete and embodied absence, they are continued to a context of strict immanence, limited to the representation of ghostly apparitions. Yet they haunt. They become not a symbol of loss but the embodiment of the process of remembering itself; the ruined place itself remembers and grows lonely.

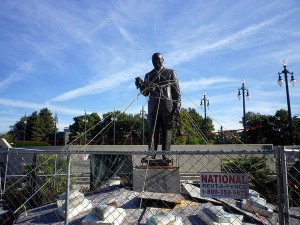

Louis Armstrong Park, November 2010. Via.

Michael Taussig, My Cocaine Museum

Essential to this montage was the merging of myth with nature that had so appealed to Benjamin in his study of the figure of the storyteller. Here, history as ruin or petrified landscape took center stage, as if the succession of human events we call history had retreated into stiller-than-stiller things entirely evacuated of life – like those monumental things, those great bodies of gravel… millions of cubic yards heaped in the jungle, moved by the hands of slaves and now covered by forest.

Ann Laura Stoler, “Imperial Debris” in Cultural Anthropology, 23(2)

In its common usage, “ruins” are often enchanted, desolate spaces, large-scale monumental structures abandoned and grown over. Ruins provide a quintessential image of what has vanished from the past and has long decayed. What comes most easily to mind is Cambodia’s Angkor Wat, the Acropolis, the Roman Coliseum, icons of romantic loss that inspired the melancholic prose of generations of European poets who devotedly made pilgrimages to them. In thinking about the “ruins of empire” we explicitly work against that melancholic gaze to reposition the present in the wider structures of vulnerability and refusal that imperial formations sustain… to what people are “left with”: to what remains, to the aftershocks of empire, to the material and social afterlife of structures, sensibilities, and things. Such effects reside in the corroded hollows of landscapes, in the gutted infrastructures of segregated cityscapes and in the microecologies of matter and mind. The focus then is not on inert remains but on their vital refiguration. The question is pointed: How do imperial formations persist in their material debris, in ruined landscapes and through the social ruination of people’s lives?