Nicholas Negroponte famously insisted that the dotcom boomers, “Move bits, not atoms.” Ignorant of the atom heavy human bodies, neuron dense brains, and physical hardware needed to make and move those little bits, Negroponte’s ideal did become real in the industrial sectors dependent upon communication and economic transaction. In the communication sector, atomic newspapers have been replaced by bitly news stories. In the transactional sector, coins are a nuisance, few carry dollars, and I just paid for a haircut with a credit card adaptor on the scissor-wielder’s Droid phone.

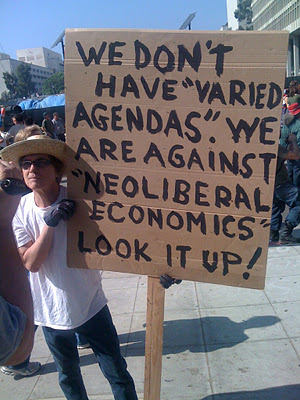

The human consequences of the bitification of atoms go far beyond my bourgeois consumption. This shift, or what is could simply be called digitalization, when paired with their very material transportation systems or networked communication technologies, combines to form a powerful force that impacts local and global democracies and economies.

What are the local and political economics of granularity in the space shared between the fiduciary and the communicative? To understand the emergent political economy of the practices and discourses unifying around mobile media and digital money we need a shared language around the issue of granularity. Continue reading