The July 29, 2010, cover of Time Magazine features a portrait of a young woman from Afghanistan, her dark eyes arresting the reader and where her nose would be there is only a terrifying scar encircling a single, fleshy hole. The headline is “What Happens If We Leave Afghanistan” and the subheading reads, “Aisha, 18, had her nose and ears cut off last year on orders from the Taliban because she fled abusive in-laws.”

Even without the headline it is a deliberately provocative photograph and one that will surely sell a lot of magazines. Contextualized by its headline the cover is pure propaganda. It makes plain the strange ideology of America’s foreign wars: We are at war with (fill in the blank) for their own good. What happens if we leave Afghanistan? Women will have their noses cut off, willy-nilly. You don’t want that do you? Presumably if we leave Afghanistan then Afghani civilians will no longer be accidently killed or mutilated by drone attacks either… those survivors didn’t get a Time-Life photographer though.

Both are acts of violence, Aisha’s disfigurement at the hands of the Taliban and civilizan casualties at the hands of the American military. But the former graces the cover of a major, mainstream media publication because it resonates powerfully with American traditions of belief about “other” people. The Taliban are barbarians and their violent behavior is symptomatic of their temporal displacement, they are literally living in the past rebelling against modernity. And so it is the duty of Civilization to intervene and save them from themselves by making them more like us. By force if necessary.

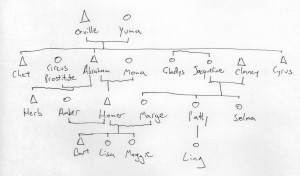

In conference papers I have argued that the genesis of this ideology is to be found in the formative conflict of the American nation, the Eastern and Western Indian Wars. Throughout the nineteenth century in political, academic, and journalistic circles American violence against Indians was seldom justified in crude materialist concerns like the acquisition of land. Instead experts created a panopoly of deficiencies inherent in the tribes’ supposed savagery that needed only to be replaced by the Protestant work ethic and the spirit of capitalism for them all to become productive members of society. “Kill the Indian and save the man,” was one such rallying cry that Americans should keep the “promise” made to all Indians — to save their souls, teach them English, and make them modern. To make them into versions of us.

Two forms of violence, one is disturbing and senseless, the other distressing but necessary. Two forms of violence, the former justifying the later. What are the means by which American people distinguish between the two? What accounts for the absence of Afghani civilian casualties on the cover of Time? For anthropologist Gabriele Marranci the legitimization of Civilization’s violence can be understood through culture, especially Christian eschatology.

In the West, anthropologically, suffering from acts of war or terrorism (terms which, in today’s Afghanistan, are often used to include national resistance, secular insurgency and territorial disputes) seems to be classified into two distinct categories. On the one hand, the western-induced suffering is perceived as ‘ethnical’ and ‘lawful’, superior and enlightened, an act of ‘love’, a bitter medicine for the salvation of the ‘ignorant’ (understood as ‘not knowing’), the ‘sinner’ through the redemption of blood, and as death with a view to societal resurrection and rebirth. On the other hand, however, there is a perception of a need for punishment of the barbaric actions of the ignorant, of the infliction of evil for the evil committed by people who are somehow disgusting for rejecting the ‘Truth’.

That is, violence and suffering are not condemned for the effect they have on human beings, but are condemned and rejected only if they are not the ‘right’ violence, ‘salvific’ in nature and ‘just’ in cause – in other words, a transubstantiational violence. Hence, destruction and suffering, in this case, is a part of redemption, while the Taliban’s violence is merely destructive.

In this light the old theoretical tools of anthropology — myth, ritual, sacrifice, the gift — all seem fresh and relevant again in the context of international violence and geopolitics. Baudrillard’s hyperreality could be useful too as the circulation of signifiers, let loose from their signifieds, flows permiscuously from Central Asia through the great nodes of global capitalism and on into the blogosphere.

So readers, what is your interpretation of the Time Magazine cover? I’m not asking about the content of the article, but the image and it’s headline. Does it suggest to you a realism that offers a way of understanding living Afghani people? Does it offer any insight into the nearly decade long war that has cost so much in American life and treasure? Or does it, as I argue, stand as evidence of an American epistemology of the Other, showing how Americans arrange what it is that they think they know about the people of the world?