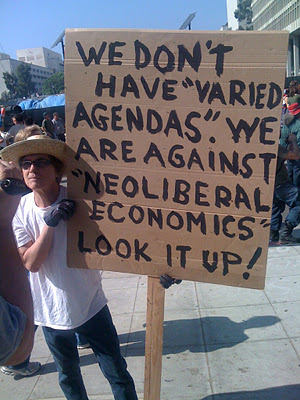

I keep returning to the public sphere as Habermas originally described it as I think about progressive political movements of today: Occupy Wall Street and its global dimensions, Anonymous and its more theatrical and political wing LulzSec, and progressive and independent cable television news network Current. Internet activism, television news punditry, and street-based social movements each work together implicitly or explicitly to constitute a larger public sphere. As scholars we need to resist the temptation of excluding one form of resistance as being inconsequential to social justice or to analysis and instead see all three as working together in a media ecology.

Tag Archives: North America

Home Economics and the Nation Against the State

If you’ve been following coverage of the federal budget crisis in the mainstream media in even a cursory manner, then you’ve probably heard some variation on what I call the Home Economics trope. I get a fair share of my news from NPR and the Washington Post and I encounter it regularly. It made me curious and I wondered what other anthropologists might make of it. A handy rhetorical scheme which crops up again and again, it is a framing device for organizing and make sense of esoteric national fiscal policy in familiar, quotidian terms. It also seems to be doing some nationalist work at the expense of delegitimizing the state. Or something like that.

It goes like this. The federal government’s response to financial crisis ought to mirror those of a typical family experiencing monetary hardship. If the family has bills to pay and can’t afford its current lifestyle then the parents are going to have to work extra hours or get a second job to supplement income (increase taxes and revenues), everyone is going to have to make do without certain luxuries like cable TV and fancy cell phone plans (make spending cuts), and the family ought to hold a garage sale to sell off extra things (privatization of land and natural resources). I’ve heard variations of this trope, in whole or in part, espoused by people of diverse political sympathies, from participants on radio call-in shows, from reporters and pundits. I wouldn’t be surprised to hear an elected official use it.

What does it mean that people are inclined to think of the federal budget in the subjunctive, as if it were like the budget of a typical household? What “work” does it do for the people who espouse it?

Continue reading

Eco-Chic Burning Man Hipsters

That curious identity politic that mixes neo-primitive fashion, ecological coolness, spiritual openness, upper middle class ambition, multiculturalism, and conscious consumerism can be coalesced under the moniker eco-chic–an elite contradictory expression of social justice and neoliberalism. It will be explored in the conference Eco–Chic: Connecting Ethical, Sustainable and Elite Consumption, put on by the European Science Foundation in October. The conference organizers see this expressive culture accurately in its rich contradictions. Eco-chic “is both the product of and a move against globalization processes. It is a set of practices, an ideological frame and a marketing strategy.” If you’ve spent anytime in Shoreditch, Haight, Williamsburg, or Silverlake you’ve got some experience with these hip, trendy elites. Ramesh calls them “Burning Man Hipsters.” I’ve been studying new media producers in America and eco-chic describes an important cultural incarnation of these knowledge producer’s value set. As far as anthropology is concerned, meta-categories such as eco-chic, liberalism, or transhumanism that cross cultural boundaries while remaining bound by class, challenge our discipline to revisit totalizing notions such as “culture” and “tribe.”

Eco-chic, like many other socio-cultural manifestations of neoliberalism is rife with contradiction. The fundamental contradiction being that it is a social justice movement within consumer capitalism. The producers of eco-chic goods and experiences are structured by capitalism’s profit motive. Likewise consumers of eco-chic goods and experiences are motivated by ideals that try to transcend or correct the ecological or deleterious human impacts of capitalism. Thus both producer and consumer of eco-chic are caught in a contradiction between their social justice drives and their suspension in the logic of neoliberalism. Eco chic events such as Burning Man and television networks such as Al Gore’s Current TV also express the fundamental contradiction between the social and the entrepreneurial in social entrepreneurialism. How do the contradictions within eco-chic represent themselves in American West Coast’s cultural expressions such as Burning Man and Current TV? Continue reading

Netroots, America, and Progressivism

Honestly, I did not know what a “progressive” really was until working the videocamera for Free Speech TV at the 2011 Netroots Nation conference in Minneapolis lat month. I thought a progressive was just another name for a Democrat or a liberal. I was wrong.

It is corny to admit it but what I discovered was a worldview and mode of political action that aligned with my own belief system as a person and an anthropologist. The core concept of progressivism is progress–that culture changes through time because of the actions of vision-driven groups and individuals. Now, how much agency individuals actually have to enact cultural change is a hotly debated topic in both political and academic circles but few disagree that “a small group of thoughtful people could change the world. Indeed, it’s the only thing that ever has” as it was that activist anthropologist, Margaret Mead, who said that most famous of hummus container quotes.

Progressive philosophy is aligned with the base theory of cultural anthropology, that is: culture is not a static or conservative thing that we need to stabilize at some nostalgic and unrealistic moment but rather a dynamic process. Progressives want to direct that process towards a more inclusive future. Progressives are not hung-up on retaining or reverting to an antique sense of ethnic, gendered, or national purity. They don’t romanticize some false sense of the securities of 1950s Americana. However, as I will describe below, The American Dream as a concept was a focal point for progressives at Netroots Nation this year. Continue reading

Illustrated Man, #5 – Journey to Cahokia and Jingle Dancer

Can anthropology be for children? Should anthropology be for children? In this installment of Illustrated Man we turn our attention to two picture books from the juvenile stacks of my local public library.

Books for children can, on occasion, offer a clarity into underlying issues that belies their apparent simplicity. In the introduction to the revised edition of Enjoy Your Symptom, Lacanian philosopher Slavoj Zizek seizes on this:

Whatever the vicissitudes and deformations of Lacan in cultural studies, one should focus on what happens with children in their early age, following the wise Jesuit motto, “Give me a child till he is seven, and afterward you can do with him whatever you want.” So I am tempted to claim that there is hope for us Lacanians as long as American children are massively exposed to Shel Silverstein’s two classic books, The Missing Piece and The Missing Piece Meets the Big O; one is almost embarrassed by the direct way these two books render in naked form the basic matrix of the Lacanian opposition of desire and drive.

I too have felt the profound touch of picture books like Leo Lionni’s treatise on epistemology and the non-translatability of experience, Fish is Fish, or Jon Muth’s tranquil and enlightening, Zen Shorts. Kids’ books are big business and tenure track positions are getting harder to find. Maybe there are some anthropologists out there who want to get in on this genre?

With the AAA’s push for a more “public anthropology” we might consider too the role our discipline can play in K-12 education. I’m not talking about the anthropology of education or an anthropology of children like the work being done by the good people at the CAE, which is in itself fascinating and, of course, vitally important given the politicization of ed discourse in the public sphere. But, imagine instead an anthropology for children. Maybe there’s a CAE person reading this now who can add to our discussion, are there anthropologists out there right now writing to children?

There are a number of kids’ books that brush up against anthropology or that invite one to interject an anthropological spin on things. At my house we have a slew of these “people around the world” type books (all of them gifts), including ones on bread, shoes, houses, and families. The DK Eyewitness series offers beautiful picture books on archaeology, mythology, Indians, classical ancient societies – Egypt, Greece, Rome, the biggies – even evolution and early humans (or as my kids call them “Monkey People”). The archaeologists already got Indiana Jones and Laura Croft. With cool how-to books like this one they need someone to move into Bill Nye territory.

Granted works like the DK series are commercial productions for the kiddie book market. They’ve no doubt got academics serving as consultants or fact checkers, but most of the creative work is done by graphic designers and copy writers who know how to make books that kids want and that parents will buy. That’s why I find the two works I’d like to discuss today so interesting. They are artistic works of scholarship and experience, creatively rendered and engaging to young people. For any anthros wanting to write for children, here are some role models

Continue reading

Why Are Evolutionary Psychologists Less Intelligent than Other Mammals?

Santoshi Kanazawa is an evolutionary psychologist who blogs for Psychology Today. If I were as stupid as he is I’d probably shoot myself, but that didn’t stop someone at the magazine from letting him post the nonsense of Why Are Black Women Less Physically Attractive Than Other Women? (The same people who don’t know how to use capitalization in titles, maybe…)

The article disappeared pretty quick (the link above is to the Google cache), so either someone at the magazine had a lucid moment or they don’t know how to work their Internet thingies, but either way, it’s out there and it bears the imprimateur of a pretty mainstream magazine.

Here’s the gist: During interviews for a longitudinal study of American adolescent health called Add Health, researchers assign a score for how attractive their subjects are, using a scale of 1-5. Kanazawa takes those objective-because-it’s-a-number-yo! figures and averages them by race, does a little factor analysis, and concludes that black women are objectively less attractive than all other women. And after discarding a few factors like the “fact” that black women are fat and stupid (which, he points out, doesn’t seem to hurt black men much, who are seen as the most attractive of men), Kanazawa concludes it must be because black women are so testosteroney.

We will NOT be seeing Mr. Kanazawa on Are You Smarter than a Fifth Grader? Continue reading

Critical Pessimism & Media Reform Movements

The American satellite television network Free Speech TV asked me to write up a blurb for their monthly newsletter about my participatory/observatory trip with them to the National Conference on Media Reform in Boston. This is my attempt at what Henry Jenkins calls “critical pessimism”–an “exaggeration” that “frighten readers into taking action” to stop media consolidation, exclusion, and the absence of televisual diversity.

Free Speech TV at the National Conference on Media Reform

From its inception in 1995, Free Speech TV’s goal has been to infiltrate and subvert the vapid, shrill and corporately controlled American television newscape with challenging and unheard voices. Fast forward to 2011, and in the age of viral videos, social media and ubiquitous computing, the same issues persist.

An excellent young pro-freedom-of-speech organization, Free Press, called all media activists to Boston for the National Conference on Media Reform (NCMR), April 8-10, to celebrate independent media and incubate strategies to fight the tide of corporate personhood, monopolization in communication industries, and the denial of access to the public airwaves.

These are issues FSTV has long fought, first with VHS tapes of radical documentaries shipped to community access stations throughout the nation, then through satellite carriage in 30 million homes, and now via live internet video and direct dialogues with the audience through social media.

FSTV was at NCMR in full force, covering live panels on everything from the role of social media in North African revolutions to media’s sexualization of women; developing strategic relationships with print, radio, internet and television collaborators; interviewing luminaries like FCC Commissioner Copps; and inspiring the delegates by opening up the otherwise closed and corporatized satellite television world to the voices of media activists fighting for access and diversity during a frankly terrifying period in American media freedom.

One question haunted the many stages, daises and dialogues at the NCMR: Is the open, decentralized, accessible and diverse internet – by which media production, citizen journalism and community collaboration have been recently democratized – becoming closed, centralized and homogenous as it begins to look and feel more like the elite-controlled cable television system?

For example, while we were in the conference, the House voted to block the FCC from protecting our right to access an open Internet. The mergers of Comcast and NBC-Universal and AT&T/T-Mobile loomed behind every passionate oration. And yet FSTV was there to document when FCC Commissioner Copps took the stage stating he would resist the denial of network neutrality and such monopolizing mergers.

Internationally, examples of the power and problems of the internet exist. The Egypt-based Facebook group “We are all Khaled Said” had 80,000 members, many who amassed at Tahrir Square on January 26, instigating a wave of democratization that began in Tunisia – also fueled by social media – and hopefully continuing to Libya. Two days later, however, the Mubarak regime was able effectively to hit a “kill switch” on the internet and target activists using Facebook for arrest, an activity that worked against the desires of the repressive regime. At the NCMR, Democracy Now! reporter Sharif Abdel Kouddous said, “Facebook was down … so they hit the streets. It had the reverse desire and effect that the government wanted to happen.”

In 2010, Reporters Without Borders compiled a list of 13 internet enemies – countries that suppress free speech online. The U.S. wasn’t on the list, but U.S. companies Amazon, Paypal, Mastercard, Visa and Apple were pressured to cut digital and financial support for whistleblowing WikiLeaks. The point is obvious: A vigilant press aided by an open, uncensored and unprivatized internet are necessary yet threatened and are the focus of FSTV’s coverage at NCMR.

FSTV embodies that ancient movement of ordinary people taking back power from entrenched elites. Today, every issue, from class inequality to ecological justice – is a media issue. However, our media sources, from journalists to internet and television delivery systems, are being co-opted by monopolizing corporations and lobbyists. As an independent, open and interactive television network, FSTV is an antidote to the problems facing free speech and democracy as more media power is centralized in fewer hands. Thankfully, as we found out in Boston, FSTV is not alone in this dangerous and difficult operation of media liberation.

Jenkins hyperbolically describes “critical pessimists” as people who “opt out of media altogether and live in the woods, eating acorns and lizards and reading only books published on recycled paper by small alternative presses”. This is a false exaggeration of a movement that is providing a necessary check on corporate power and mindfully working for greater civic, community, and citizen involvement in media production.

Participation, Collaboration, and Mergers

I work at UCLA’s Part.Public.Part.Lab where we investigate new modes of co-production and participation facilitated by networked technologies. Internet-enabled citizen journalism such as Current TV, public science like PatientsLikeMe, and free and open software development like Wikipedia are key foci. In the lab I investigate the vitality or closure of a moment of freedom and openness within cable television, news production, and internet video when the amateur and the alternative disrupted the professional and the mainstream. What are the promises and perils of social justice video in the age of internet/television convergence? Will internet video become as inaccessible, vapid, and homogenous as cable television? In our recent paper, Birds of the Internet: Towards a field guide to the organization and governance of participation, we draft a guide to identify two species flourishing in the internet ecology: what we call “formal social enterprises,” which include firms and non-profits, as well as the “organized publics” the enterprises foster or from which they emerge. These two types share a vertical or inverted relationship, power comes down from visionary CEOs and charismatic NGO directors to provoke rabid social media production, or a viable movement foments amongst grassroots makers that percolates upwards towards the formation of semi-elitist institutions. In light of this research and with a discreet fieldwork experience to think through I would like to clarify and address three types of social interaction: participation, collaboration, and mergers. Continue reading

Ethnography is like fishing…(h/t Marcel Mauss and James Ferguson)

I have gotten a couple of comments regarding methods, access, etc. (thanks for the comments!); I will get to those issues later this week. Today I thought I would give a description of the early portion of ethnographic research that Bloomberg’s New York is based on–a narrative of what actually happened, rather than the packaged, fabricated narrative that we as academic professionals spend so much time self-consciously producing.

First a brief backstory: from 1998-2000, I attended urban planning graduate school. Halfway through, I realized I was far more interested in analyzing cities than planning them, especially because (at that point anyway) in NYC “planning” often meant little more than manufacturing windfall profits for developers. So I headed off to the CUNY Graduate Center to work with their flock of urbanists.

Flashing forward to 2003: my dissertation research begins. The idea is for me to investigate the process by which the “business agenda” comes to be. Basically, what I am trying to do here is use ethnography to explore what happens in the gap between the functional requirements of capitalist urbanization (as laid out by Harvey, Castells, Molotch and Logan, etc. etc.) and the construction of an actual elite agenda in a specific historical, cultural, and geographical context. My focus is on the public spaces of development policy formation, such as conferences and other professional meetings, city council hearings, etc., but also on more informal mechanisms. For the latter, I draw on the network of contacts I began developing in graduate school, and I soon find out that the development policy world in NYC is pretty small and interlinked (I had an excel spreadsheet with just a couple of hundred names on it). I begin talking to people, attending those conferences, interviewing, and so on.

As I do so, I quickly realize three things. First, the Bloomberg administration is up to something different than I expect, given the standard shape of neoliberal urban governance in NYC or elsewhere. The administration is engaging in citywide urban planning, moving away from the use of indiscriminate tax subsidies, and perhaps most interestingly pulling a lot of new people into City Hall. Not surprisingly, given the new Mayor’s background in business, this includes several people from finance and other private sector industries. Less expected is the hiring of a number of very well-respected planning and policy professionals to staff the top levels of the Bloomberg administration’s development and planning agencies. Such people had largely been excluded from previous administration in favor of folks drawn from the real estate industry or from the murky world of NYC’s public-private development agencies (which basically amounts to the same thing). Bloomberg’s City Hall is becoming a hotbed corporate and professional technocracy.

Second, the Mayor’s business background (along with that of the other private sector people he was bringing into government) actually seems to matter in substantive ways. Economic development officials are telling the city council about the thorough rebranding campaign underway; city officials are referring to companies as “clients”; City Hall was being physically remodeled along the lines the Mayor had used in his private company, Bloomberg LLP; and perhaps most remarkably, the Mayor is referring to NYC as a “luxury product.” Importing private-sector logic into government is nothing new, in NYC or elsewhere, but now it is being done by people who can (and do!) credibly claim to be running the city like a private company.

Third, everybody in the development and policy world is focused on the far west side of Manhattan. Everybody. Nobody wants to talk about the business agenda formation; they want to talk about the Hudson Yards (the plan proposed for the area). The Bloomberg administration is joining NYC2012 (the city’s private Olympic bid organization), the Group of 35 (an elite commission charged with stimulating office development in NYC), the New York Jets, and a number of other planning and development groups in targeting the area to the west of Times Square and Penn Station for redevelopment. And as it turned out, graduate school classmates of mine are involved in the growing conflict over far west side redevelopment in a number of ways–some working for city agencies, others working for community organizations that oppose the plan as currently formulated.

This was a key point in my research; suddenly focusing on the process of business agenda formulation seemed a bit boring, especially since I had a full-scale development battle emerging in front of me! I also had this interesting phenomenon of the ex-CEO mayor actually running the city as a business (rather than just for business), which seemed to have some unpredictable consequences (like a willingness to raise taxes and hire egghead professors and policy professionals and respect their expertise). Finally, I had all these professionals–city planners, professors, public health experts, markets, educational experts, former management consultants, etc.–talking about the new spirit of professionalism and competence in City Hall, and the new excitement about public service that they and their peers were feeling.

Realizing all this, I began to split my research onto two tracks. First, I began investigating the early years of the Bloomberg administration, i.e. late 2001 to mid-2003, using interviews with officials, government documents, transcripts of administration testimony to the city council, and various secondary sources. Second, I threw myself into the conflict over the far west side of Manhattan, attending every community meeting, rally, city council hearing, conference, and official planning meeting I could find, and redirecting my interviewing towards those engaged in the conflict. I’ll write a bit more about the second, more ethnographic of these two tracks next time.

What I am up to

I want to thank Kerim and all the Savage Minds folks for giving me the opportunity to share my work and thoughts. Its an especially nice opportunity for me because my relationship to the mainstream of contemporary anthropology has been, if not vexed exactly, then fraught. Though I received my PhD in anthropology, though I have taught in anthropology departments for the past five years, and though, in the classroom at least, I have become a believer in anthropology’s indispensability to the well-rounded undergraduate, my writing and research has always felt somewhat oblique to the discipline and its central concerns.

That’s because I investigate issues–urban governance and urban political economy in the contemporary United States–that have generally been addressed in interdisciplinary urban studies. However, the way I investigate them–using ethnographic methods and analysis, paying close attention to my informants’ words and to detail and particularity, and by taking seriously the impact of what I will gloss here as “cultural” matters in the context of urban governance–are very “anthropological,” or at least seem so to me.

Adding to this, the people I have for the most part studied–urban planners, city officials, economic development experts, developers and so on–are generally not studied in any real depth by anthropologists or by people in urban studies. Most urban anthropologists (not all, of course) tend to focus on relatively poor, or ethnic, or working class neighborhoods; when my “people” do show up, its usually only when City Hall and developers are trying to perpetrate some kind of nefarious development scheme. In urban studies, the folks I study typically are either subsumed into the application of some larger structuralist theory of urban governance (the urban growth machine, the capitalist urban state, urban neoliberalism, etc.), or (more common now that Marxist thought has been, if not displaced as dominant in critical urban studies, then theoretically hybridized, ethnographized, and made more flexible) incorporated into nicely context-sensitive empirical accounts in a relatively one-dimensional way, as inhabitants of government positions or as avatars of commodification, rather than as three dimensional individuals with class, race, gender, educational, and other biographical/social/cultural characteristics (that is to say, in the manner that anthropologists typically portray their informants).

Urban anthropology and critical urban studies do a lot of things really well–think of how much we know about the dynamics, complexities, and social organization of poor urban neighborhoods, or about why it is that developers so often get what they want from city government–but one thing they aren’t particularly good at is providing well-rounded and robust accounts of the formation, makeup, development, history, and internal tensions of urban elites. I think this is important to do for both analytical and political reasons.

So that’s what I am up to. Hopefully it begins to explain why an anthropologist would do something like study the administration of New York’s ex-billionaire Mayor Michael Bloomberg.

Children as Animals in American Culture

Regular readers of my twitter stream probably know that I am the father of twin boys who are now crawling all over me and everything I own. I don’t generally blog about my family since I feel it is their right to leave their own data trail on the Internet, but I wanted to make an exception in this case and talk a little about how Americans dress their infants. Like many couples, my wife and I have purchased practically none of the clothing out children wear. Instead, we’ve been relying on hand-me-downs and gifts from family and friends — a pretty typical situation when kids are at an age when they outgrow clothes every couple of weeks, and families with older kids are desperate to get rid of all the stuff they accumulated when their kids were small. As a result of this, I’ve had the unusual experience of seeing what people have decided my children should wear (or, in the case of hand-me-downs, what they thought their children should wear).

I’m sure the sorts of things we’ve been given are marked by my demographics: educated, white, above average income, politically on the left, and so forth. So it’s not surprising to me that no one has yet given the kids a “gimme my shotgun” onesie or a “can’t wait to treat women as objects” shirt. Nevetheless, I still think some of the trends I see are generalizable for a lot of the country.

For instance: Why are kids so crazy about dinosaurs? Answer: because we begin covering our children’s bodies with them before their eyes can focus properly. I can’t count the number of items we’ve received with prints of animals and dinosaurs on them. Typically these are brightly colored and in graphic, even extremely abstracted form. I personally like the look. As a kid who grew up in the halcyon days before we knew dinosaurs had feathers, I sort of wish that it was acceptable for me to show up to class wearing a white blazer with red and purple happy/cute velociraptor faces all over it. Alas, apparently that is hors d’categorie for adults.

It might seem shocking that we so closely associate our children with carnivores, given our tendency to imagine children as innocent and non-predatory. The happiness of the animals seems to be essential here — the more carnivorous they are the more they are portrayed as harmless and friendly. It might also be that the presence of these dangerous animals near infant bodies is meant to have an apotropaic function — as does the frontlets full of spiders and scorpions that chinese children wear — but I really don’t think that is what is going on in this case.

This identification of infant and wild animal can be seen even more clearly in clothing where the child is literally dressed in animal costume. In the case of infants, reptillian identification seems to be key: I’ve seen hoods with ridges down the back, and we’ve also received green socks with three clawed toes, designed to make it appear as if my children had reptilian feet. The impulse seems similar to the trend (hopefully now extinct?) of hipster women wearing hoods and hats with small animal ears protruding from them: a riff on the ambiguous cat-as-cute cat-as-dangerous/agentive trope which seems never to get old in American culture. Much more common than dressing the children as if they were animals is putting animals body parts over their body parts, but in a non-homologous way. For instance, pajamas where the childrens feet are covered with smiling monkey heads (non-human primates are also a big theme in children’s clothing). In one remarkable piece we were given, the seat of a pair of pajamas has a large monkey face on its seat, giving the impression that my child’s GI tract terminates in the head of a large primate. Personally, I found this a little weird, but I think I do have a basic understanding of why people think it is cute to put non-matching monkey parts on baby parts — a sort of Bakhtinian carnivalesque aesthetic at work here, some sense that the mismatch of body parts is cute. but honestly, my grasp on this one is a little tenuous.

I think a major reason that Americans think that ‘culture is something other people have’ is because we do not look hard enough at our own culture. Many people see Americans — and perhaps all humans — as rational actors seeking to maximize their wealth/utility. But really — how many acultural rational actors choose to disguise their infants as giraffes? Because let me tell you something: that is something Americans love to do. You only have to quint a little, shift your perspective a bit, and you can see both that there is a cultural logic to much of our lives and that this logic is, if you stop to think about it for a second, pretty unusual. There is nothing natural and inevitable ‘in human nature’ that makes people put monkey heads on baby behinds. One of the great parts of being an anthropologist is the way an awareness of cultural logics enriches your everyday life — even if one of the downsides is explaining to people why you are so preoccupied with the fact that they just gave your child a pair of alligator socks.

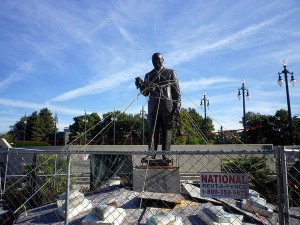

Collage for NOLA: Ruin

Walter Benjamin, “Surrealism” in Reflections

[Andre Breton] was the first to perceive the revolutionary energies that appear in the “outmoded,” in the first iron constructions, the first factory buildings, the earliest photos, the objects that have begun to be extinct, grand pianos, the dresses of five years ago, fashionable restaurants when the vogue has begun to ebb from them.

…

They bring the immense forces of “atmosphere” concealed in these things to the point of explosion. What form do you suppose a life would take that was determined at the decisive moment precisely by the street song last on everyone’s lips?

Suan Buck-Morss, The Dialectics of Seeing

More generally, throughout [Benjamin’s Arcades Project], the image of the “ruin,” as emblem not only of the transitoriness and fragility of capitalist culture, but also its destructiveness, is pronounced.

Six Flags New Orleans, October 2010. Via.

Kathleen Steward, A Space on the Side of the Road

A rambling rose vine entwined around a crumbling chimney remembers an old family farm, the dramatic fire in which the place was lost, and the utopic potential clinging to the traces of history. Objects that have decayed into fragments and traces draw together a transient past with the very desire to remember. Concrete and embodied absence, they are continued to a context of strict immanence, limited to the representation of ghostly apparitions. Yet they haunt. They become not a symbol of loss but the embodiment of the process of remembering itself; the ruined place itself remembers and grows lonely.

Louis Armstrong Park, November 2010. Via.

Michael Taussig, My Cocaine Museum

Essential to this montage was the merging of myth with nature that had so appealed to Benjamin in his study of the figure of the storyteller. Here, history as ruin or petrified landscape took center stage, as if the succession of human events we call history had retreated into stiller-than-stiller things entirely evacuated of life – like those monumental things, those great bodies of gravel… millions of cubic yards heaped in the jungle, moved by the hands of slaves and now covered by forest.

Ann Laura Stoler, “Imperial Debris” in Cultural Anthropology, 23(2)

In its common usage, “ruins” are often enchanted, desolate spaces, large-scale monumental structures abandoned and grown over. Ruins provide a quintessential image of what has vanished from the past and has long decayed. What comes most easily to mind is Cambodia’s Angkor Wat, the Acropolis, the Roman Coliseum, icons of romantic loss that inspired the melancholic prose of generations of European poets who devotedly made pilgrimages to them. In thinking about the “ruins of empire” we explicitly work against that melancholic gaze to reposition the present in the wider structures of vulnerability and refusal that imperial formations sustain… to what people are “left with”: to what remains, to the aftershocks of empire, to the material and social afterlife of structures, sensibilities, and things. Such effects reside in the corroded hollows of landscapes, in the gutted infrastructures of segregated cityscapes and in the microecologies of matter and mind. The focus then is not on inert remains but on their vital refiguration. The question is pointed: How do imperial formations persist in their material debris, in ruined landscapes and through the social ruination of people’s lives?

Digital Labor

My colleague Ramesh Srinivasan and I just submitted an article to a journal in which we analyze social entrepreneurs’ digital labor practices. The argument we are making is that one needs to focus on (1) organizational missions, cultures and histories, (2) the nature of the labor (its level of creativity or its invocation of routinized, uncreative time-motion studies!) and the level of agency for workers to choose this labor versus various alternatives, and (3) the level of capitalization of the labor, notably who profits and to what extent from the contributed work. Our case studies, Samasource, a digital labor firm that brings digital work to developing world populations, including refugees and women, and Current TV, a cable network that self describes as “democratizing” documentary production, maintain an interplay between for/non-profit and social empowerment/exploitation. Instead of waiting the 4 months for reviews, or 8 months for publication we’d love some real time feedback on some of the more illustrative examples and concerns that drive this research. (I’ll be presenting this analysis at the American Anthropological Association meeting on Friday at 5 if you prefer embodied engagement).

Jenny Don’t Change Your Number

Who is being marketed to in your neighborhood or in the communities you are studying? Enter a zip code and the Prizm market segmentation system returns five socio-economic types (out of a total of 67 possible types). What’s really fun are reading about all the different categories that the marketers have dreamt up. Here’s a flash video that provides a glimpse into how the data were generated and organized.

Here’s some PRIZM segments from my life’s geographies–

Where I currently live, Newport News, VA:

- Blue Chip Blues — a comfortable lifestyle for ethnically-diverse, young, sprawling families with well-paying blue-collar jobs

- Domestic Duos — a middle-class mix of mainly over-65 singles and married couples living in older suburban homes

- New Beginnings — households tend to have the modest living standards typical of transient apartment dwellers

- Park Bench Seniors — With modest educations and incomes, these residents maintain low-key, sedentary lifestyles. Theirs is one of the top-ranked segments for TV viewing, especially daytime soaps and game shows.

- Suburban Sprawl — they hold decent jobs, own older homes and condos, and pursue conservative versions of the American Dream

The field site for my dissertation, Cherokee, NC:

- Back Country Folks — residents tend to be poor, over 55 years old, and living in older, modest-sized homes and manufactured housing

- Bedrock America — With modest educations, sprawling families, and service jobs, many of these residents struggle to make ends meet. One quarter live in mobile homes. One in three haven’t finished high school.

- Blue Highways — the standout for lower-middle-class residents who live in isolated towns and farmsteads. Here, Boomer men like to hunt and fish; the women enjoy sewing and crafts, and everyone looks forward to going out to a country music concert

- Crossroads Villagers — a classic rural lifestyle. Residents are high school-educated, with downscale incomes and modest housing; one-quarter live in mobile homes.

- Shotguns and Pickups — scores near the top of all lifestyles for owning hunting rifles and pickup trucks. These Americans tend to be young, working-class couples with large families

Where my parents live, in a swanky part of Austin, TX:

- American Dreams — In these multilingual neighborhoods–one in ten speaks a language other than English–middle-aged immigrants and their children live in upper-middle-class comfort.

- Bohemian Mix — ethnically diverse, progressive mix of young singles, couples, and families ranging from students to professionals. In their funky row houses and apartments, Bohemian Mixers are the early adopters who are quick to check out the latest movie, nightclub, laptop, and microbrew.

- Money & Brains — high incomes, advanced degrees, and sophisticated tastes to match their credentials. Many of these city dwellers are married couples with few children who live in fashionable homes on small, manicured lots.

- Urban Achievers — the first stop for up-and-coming immigrants from Asia, South America, and Europe. These young singles, couples, and families are typically college-educated and ethnically diverse

- Young Digerati — Affluent, highly educated, and ethnically mixed, Young Digerati communities are typically filled with trendy apartments and condos, fitness clubs and clothing boutiques, casual restaurants and all types of bars

I read about this first in the librarian blog/ webcomic, Shelf Check, a must read for anyone who harbors a secret crush on librarying. Posey writes that she saw it first in Lifehacker.

Glenn Beck, archaeologist

Celebrity conservative and goldbug, Glenn Beck, made an interesting argument this past Wednesday, August 18, on his Fox News show — since 2009, the most watched news program on television’s most watched news network. Beck contextualized this segment as part one in a three part series on Civil Rights in America.

Here the Hopewell earthworks with their numerological connection to the pyramids of Giza are being deployed as evidence that North America was a site of divine providence. The Bat Creek stone, originally found in Tennessee in 1889, is supposed to be evidence of pre-Columbian Jewish migration west from Phonecia across the Atlantic. Later in the segment a guest offers Tisquantum’s (Squanto) discovery of the Plymouth colonists as another example of divine providence.

The foil to Beck’s argument about divine providence, that America is special in the eyes of God and that the Founding Fathers were doing God’s work on Earth, is what he terms manifest destiny. For Beck manifest destiny is a perversion of divine providence. He states, “Manifest Destiny is, get out of my way, my way or the highway, because I’m on a mission from God. That is Manifest Destiny. That’s Woodrow Wilson. That’s Andrew Jackson. That’s not George Washington. It’s different.”

According to Beck, the purpose of this lecture is to reveal a history that “the Smithsonian, science, government, and commerce colluded to erase.” He continues, “The history that has been erased in our nation and, in particular, with the Native Americans, happened because it didn’t fit the story they created – manifest destiny. It only works if the Indians were savages. And they had to have savages for commerce and government to expand. The ancient artifacts prove otherwise. Why aren’t we looking into those?”

I think its unfortunate that archaeology, perhaps the most popular and most public face of anthropology, is so frequently hijacked by amateurs for nationalist and religious ends. The blog A Hot Cup of Joe just did a noteworthy post on this very topic. With the authority and authenticity that so many cultures ascribe to events in the past a material remainder can, like a fetish, carry great power. An actual physical object from the distant past that is undeniably real to the touch is proof that people were here before and the certainty of that physical reality is conveyed, like Frazer’s principle of magical contagion, onto ideologies making them just as real.

It’s doubly unfortunate that living American Indian people have to put up with this manipulation of the past to suit the ends of non-Indians. On August 13, Indian Country Today reported that the Cherokee Nation was filing suit against the state of Tennessee for extending state recognition to six groups that the Cherokees believe to be fraudulent. Included in this group of six are the “Central Band of Cherokee” which claim to be a Lost Tribe of Isreal.

Meanwhile on Glenn Beck fansites, his viewers did not give the above performance high marks. A common concern expressed on discussion boards was that the history lesson resonated too closely with Beck’s Mormon faith and they feared that the stigma attached to Mormonism would lead some to question their fandom of Beck, possibly leading to less enthusiasm for his general political agenda that they so highly value.

This case is a prime target for the Bad Archaeology blog and I hope they choose to write it up.