By: Faye V. Harrison, Carole McGranahan, Matilda Ostow, Melissa Rosario, Paul Stoller, Gina Athena Ulysse and Maria Vesperi

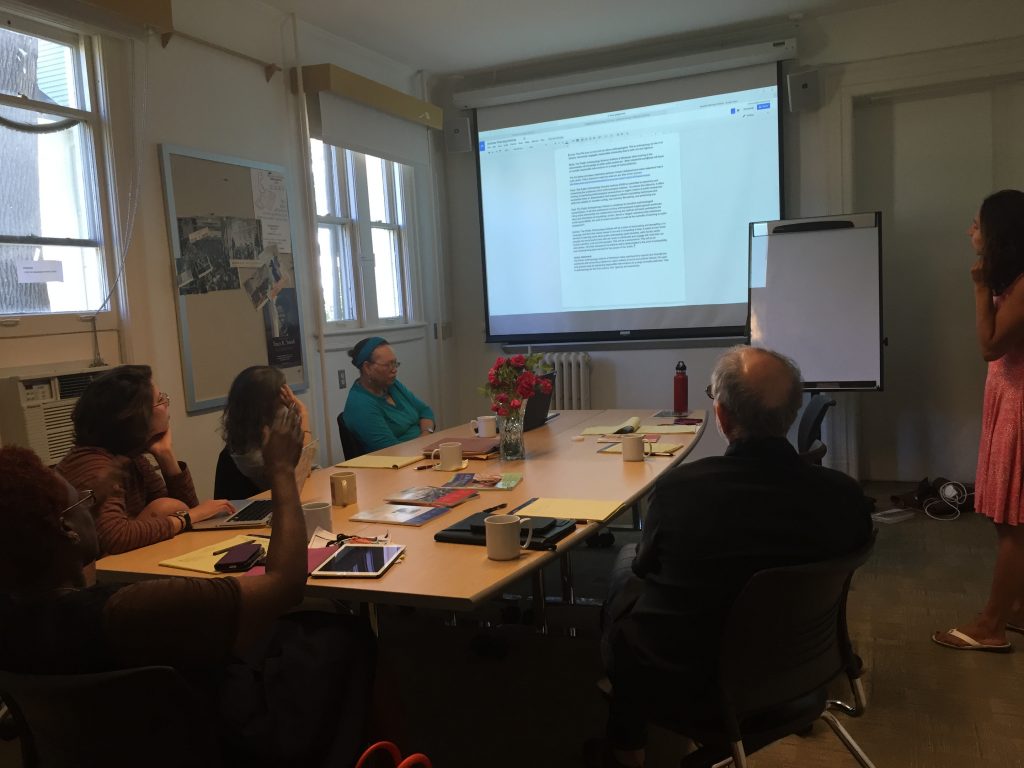

The massacre in Orlando was just two days before we sat together around a seminar table in an idyllic New England college town. A massacre of forty-nine people out dancing, celebrating life in a gay nightclub called Pulse. They were mostly young, queer, and Latinx. Gone. Already stories had turned to focus on the killer’s motivations. Was this primarily homophobic homegrown terrorism or the machinations of the Islamic State? We were meeting at Wesleyan University in Connecticut to discuss the creation of the Public Anthropology Institute (PAI) and contemplate ways to use our scholarly knowledge of cultural difference for greater service globally. Given the disheartening public debate in this moment reminiscent of Dickens’ best and worst of times, we were convinced that this work is necessary in the face of such violence and hate.

For too long anthropologists have retreated into the minutia of arcane disciplinary debate even when our knowledge can make a difference. It can be intellectually stimulating and important to turn inward, but conversations among ourselves cannot be the only ones we have. We also need to create work with a larger impact and a longer reach. As scholars who have studied across the global south and thought deeply about geopolitics, poverty, social and economic inequality, racism, homophobia, sexism and climate change, we believe it is time to reconnect with the obligation to produce knowledge that makes the world a better place. As the stakes get higher, anthropological perspectives can make critical, unexpected connections and offer direction beyond the logic of dominant assumptions. Continue reading