Since we’ve just entered the 10th year of U.S. military intervention in Afghanistan (well, 10 years this century) it seems a good time to say a few words about Breaking Ranks: Iraq Veterans Speak Out Against The War (University of California Press 2010) co-authored by Matthew Gutmann and Catherine Lutz.

Breaking Ranks recounts, largely through interview excerpts, the stories of six Iraq War veterans who became involved with Iraq Veterans Against the War (IVAW) and other military anti-war organizations and participated in the larger GI Rights Oral History Project. It takes us from their decisions to join the military, through combat, anti-war epiphanies, homecomings, and involvement in anti-war activism.

The patchwork composition of the book reflects the veterans’ attempts to piece together a narrative of their lives defined by the watershed of their experiences in Iraq. While book’s overall structure parses these experiences into a general arc of life—from enlistment, to the shock and fog of war, to political awakening, to struggles with trauma, to activism—it doesn’t smooth over the rough edges of these experiences or impose too clear an order on the muddle of reflexive memories that the soldiers offer.

As the authors note in the introduction, the book is an account of how these six people (five men and one woman; three soldiers, one sailor, one Marine, and one National Guardsman) found their way to a public, anti-war position and of “the striking and original ideas each developed to understand the war and what it meant. Their critiques are not simple matches to those of the civilian antiwar movement or to our own as authors” (8). Thus Breaking Ranks suggest that while it is possible to speak of a single anti-war movement, that singularity subsumes a multiplicity of different meanings and the ones we hear here are not always foregrounded.

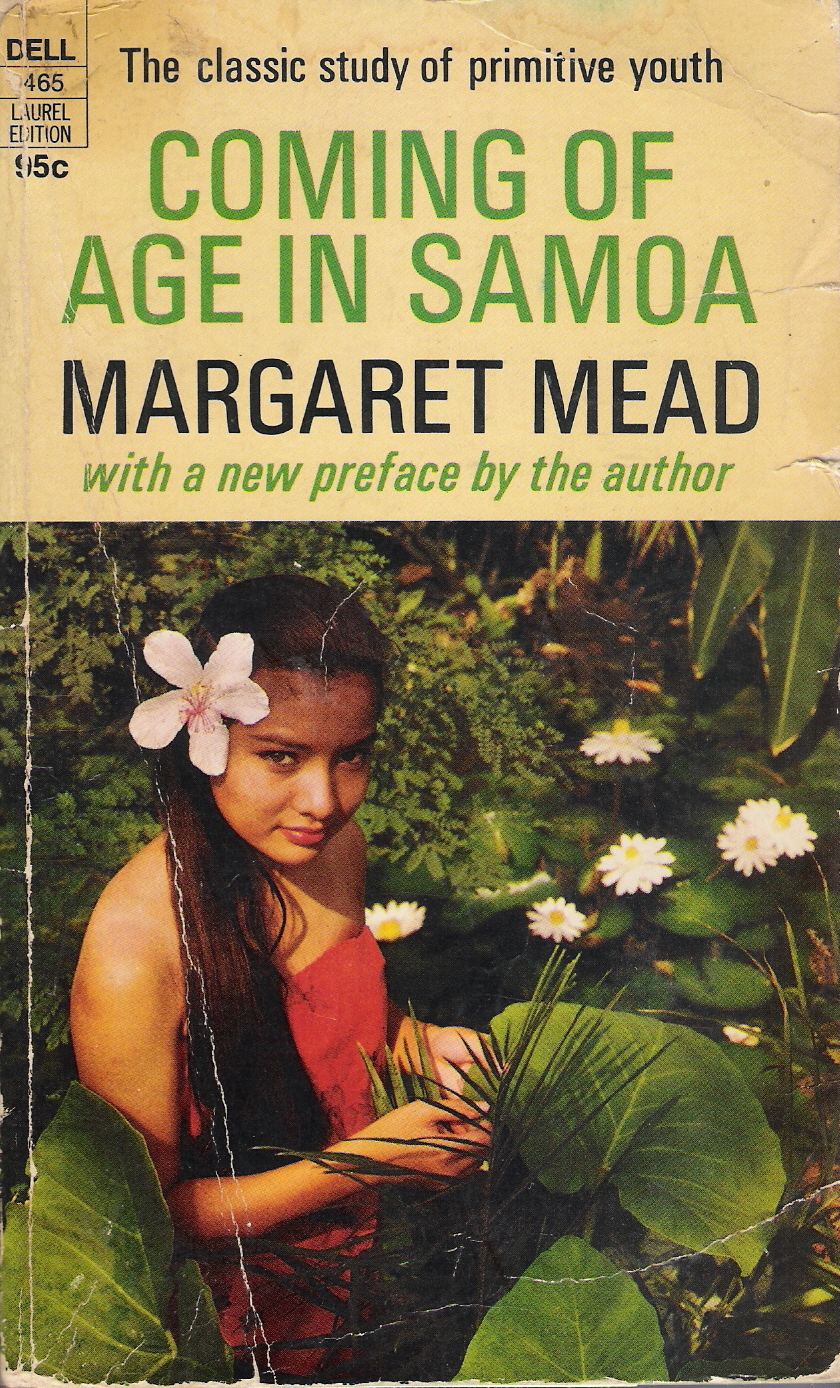

Gutmann and Lutz’ Zinn-ian project of documenting the grassroots critiques so often written out of American History is well complemented by their anthropological attention to the little details of daily life (in the military, at war, and after) that aggregate into feelings of frustration and individual acts of political resistance, suggesting the complex and divergent paths through which soldiers come to, as they say, “speak out”.

Thought the text of the book is devoted to six stories, it is also peppered with facts and events that position these very diverse lives within a single post 9/11 historical moment which is also linked, by both the authors and the subjects, to the American legacies of the Vietnam War and its contemporary anti-war motifs.

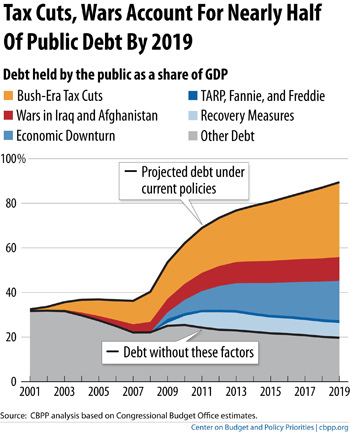

In their curation of the stories, Gutmann and Lutz also demonstrate the ways that war insinuates itself into civilian life in America, making military service seem like the best possible option for many Americans whose lives are made hard or unstable by the exigencies of family expectations, national pride, poverty, and youth. The Introduction and endnotes are also full of data and resources for further reading about the ‘dark side’ (as Alex Gibney might say) of America’s war in Iraq.

Lately, ‘the good war’ in Afghanistan is consuming more and more of America’s attention and resources and, in the months since Breaking Ranks was released this summer, American combat operations in Iraq have been declared over (again) and the ‘draw-down’ of combat troops and ‘civilian surge’ there have begun. In this context, we can read in Breaking Ranks deeper questions about the different justifications for American military interventions in Afghanistan and Iraq at the level of individual experience and public discourse alike, as well as about the fundamental nature of wars in which nation-states confront non-state entities through the sanctioned, violent acts of their citizens. As our attention, and perhaps attitudes, to America’s two main post-9/11 military operations seems to be shifting, Braking Ranks can help readers think about how things have (and haven’t) changed in military life and policy at home and down range.

In addition to being a powerful documentary record and conversation starter about the Iraq War, Breaking Ranks strikes me as an important, accessible, and eminently teachable book that speaks of the conflicted experiences of soldiers in war, the political failings of America’s doctrine of pre-emptive war, and the contingent evolution of personal conflict into political action. It would be well suited to undergraduate classes on war, trauma, social movements, public or activist anthropology, and—given its format—methods courses that discuss life-story interviews and practices of ethnographic writing.

[A bit of full disclosure: Royalties from Breaking Ranks are being donated to IVAW; an organization with which I did some fieldwork in 2008 and which I’ve personally supported]