Savage Minds welcomes guest blogger Vidula G. Khanduri. A STEM major at Wellesley College, Vidula enjoys dabbling in the crossroads of politics, science, technology, and society. She’s an avid reader of graphic novels and mystery books, is a skilled makeup artist, and loves to sing classical music.

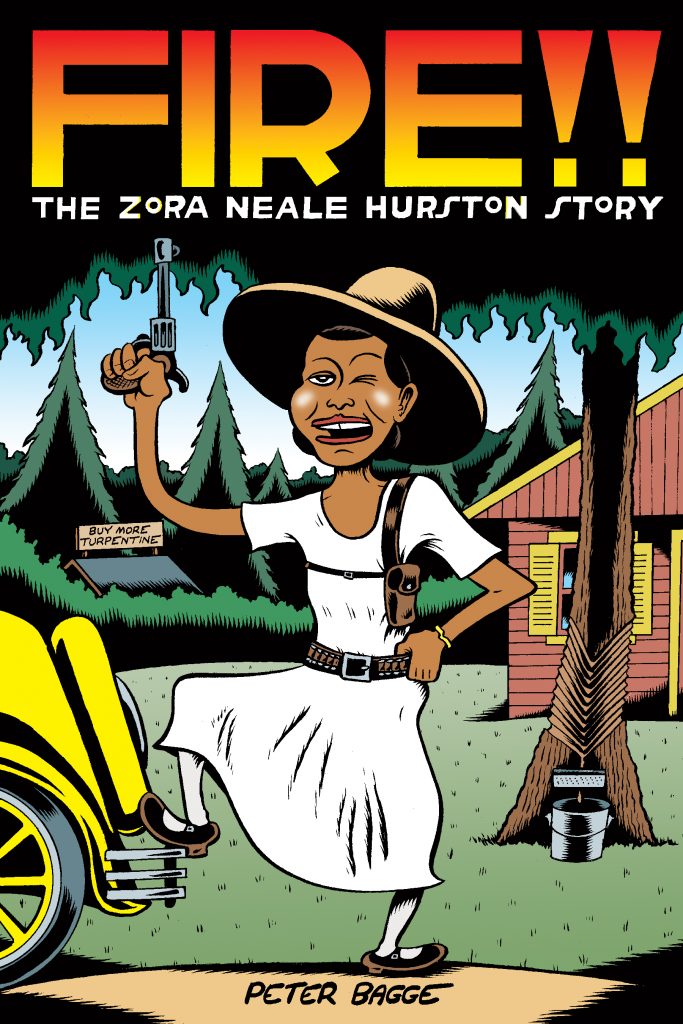

Fire!! The Zora Neale Hurston Story.

By Peter Bagge

72 pp + notes. Drawn and Quarterly. 2017.

Review by Vidula G. Khanduri.

Author, anthropologist, and feminist Zora Neale Hurston (1891-1960) stood out among her peers during the Harlem Renaissance. She bent norms: denouncing communism, wearing unique clothing, and embracing social imperfections. Her books narrate black American life, “warts and all,” unlike the works of Langston Hughes, W.E.B. DuBois and other black literary figures, who accounted for white perceptions of the black community. Hurston’s impact on literature was long forgotten until Alice Walker revived her works in the 1970s. Her grave was left unmarked and untended for years. Since then, Hurston’s novels, especially Their Eyes Were Watching God (1937), have found spots in college syllabi all over the country. Named after an unsuccessful black literary magazine Hurston and her colleagues created in criticism of Harlem politics, Peter Bagge’s Fire!! The Zora Neale Hurston Story narrates her life from start to finish in a graphic form as colorful as Hurston herself.

Bagge’s cover art turns the iconic Hurston – sitting, holding a cigarette between her fingers – on its head. The front cover is a composite picturing Hurston at a turpentine camp where she conducted fieldwork, donning the new Stetson hat, car, and shotgun she was notorious for spending her whole anthropological research grant on. Bagge consistently illustrates Hurston wearing bright yellow – homage to her commanding and bold personality. Episodes of dispute, frustration, excitement, and frenzy stand out as silhouettes in black and white panels.