“I elaborate entanglements with their gnarly knots that defy orderly undoing.” (Donald Moore, Suffering for Territory, p. 9)

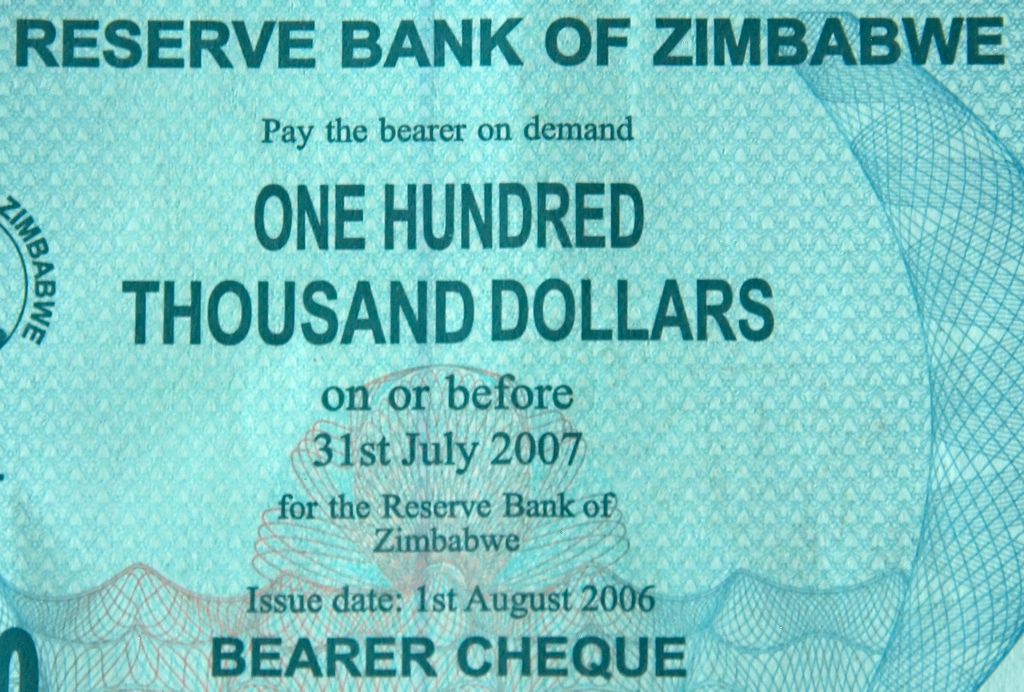

The first thing I noticed about Donald Moore’s Suffering for Territory is that the preface and the flap-copy both describe events in Zimbabwe since 2000– the globally significant displacement of white landowners by the Mugabe government– but the research conducted in the book occurred in the early 1990s. At first sight this looks like a way to sell the book (it’s not out of date, it’s background!), but in reality I think there is something much more complex about this book that isn’t articulated until one gets well into the intro: that this is a book for understanding why the events of the last few years make sense. Whereas the news media and the fast-paced world of journalism are excellent at covering and tracking unfolding events, especially in places with dramatic political conditions like Mugabe’s Zimbabwe, ethnography is after something that journalists (insofar as they are not really participating in what they observe) cannot articulate.

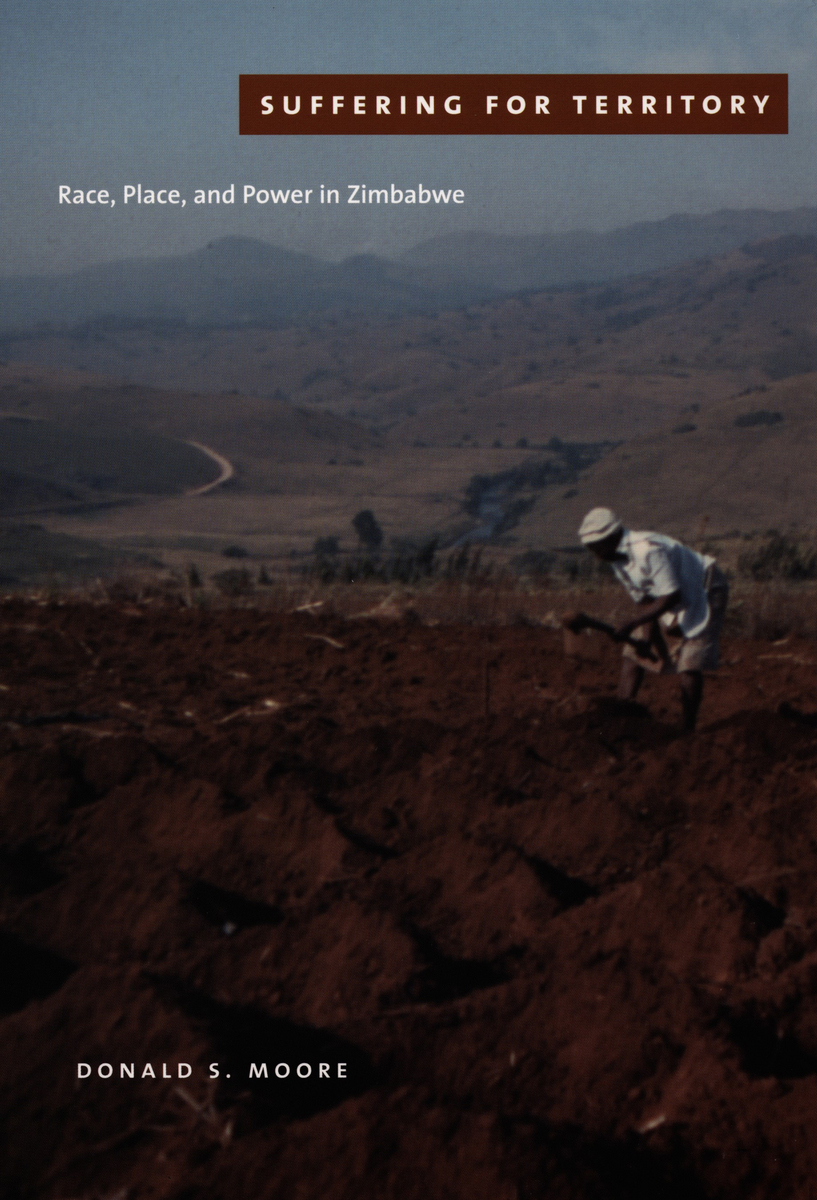

Unfortunately, that same sense-making skill that anthropologists develop is also the reason why it is so often hard for people (including authors themselves) to say what an ethnography is “about.” Certainly Donald Moore’s book is “about” Zimbabwe, and in particular, a little district in the north east called Kaerezi, and in particular a little village in that district. But to relegate the book to being merely about this village would miss the fact that it is actually (also?) about how power, sovereignty and discipline make space and place look, and happen, the way they do. But to say that it is merely a theorization of governmentality would miss the fact that it (also?) is about race, colonialism, African histories of liberation, resistance, genocide and suffering… and so on.

Fortunately for Moore, and for me, one of the perquisites of anthropology is that one can address novice and expert at the same time. I, for instance, had to look at a map to know where Zimbabwe is exactly, so I am very much a novice when it comes to one thing the book is about. But when it comes to the parade of familiar theorists (Foucault, Gramsci, Dolce and Gabanna, Appadurai, Lefbvre, James C. Scott, Chakrabarty, etc), I’m an expert whose own classes, syllabi and work have struggled to makes sense of things like governmentality, sovereignty, assemblages, articulations, situated ethnographies, space and place. The real challenge, for Moore’s book, is to integrate novice and expert– to make sense of something that is inevitably highly specific and particular, in terms that make it make sense at a global and historical level (and not only in terms of “governmentality”, but generally, as an ethnographic explanation of a situation, not just a particular place or set of people).

Of course, if you are looking for that elusive thing called fieldwork or ethnography (you know what I’m talking about, that thing that you can’t name but that when it is missing makes people say “where’s the ethnography”) then Moore’s book promises to be as rich a monograph of a specific locale as one could want: during fieldwork, Moore was detained by government officials at the airport, subjected to ruthless and pointless bureaucracy, had successive meetings with people in power overseeing his ability to work, was the subject of a public meeting deciding his fate, lived in a tent in the village, built his own mud and wattle hut, worked the fields, visited the archives, and spent on the order of ten years thinking through the experience. If this isn’t ethnography, then I’d be hard-pressed to say what is. More important however, might be trying to precisely articulate what this ethnography does that others (or other accounts that do not employ this kind of fieldwork) cannot do.

Continue reading →