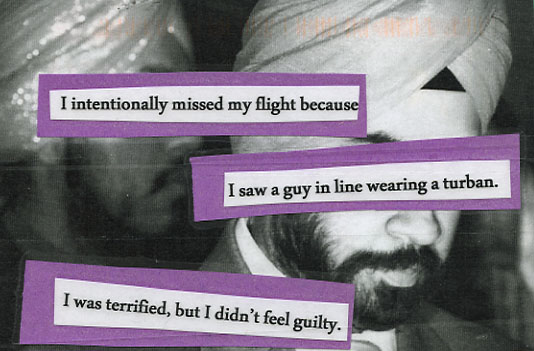

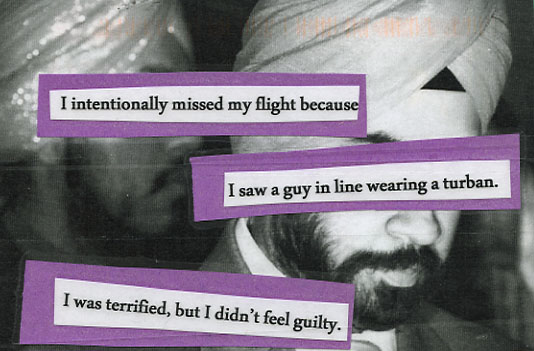

Via the PostSecret website, it is unclear whether the poster intentionally picked a photo of Sikhs or if this was unintentional irony. Not that the sentiment would have been any less offensive if the person wearing a turban was actually a Muslim. It certainly didn’t matter to the families of victims of post 9-11 hate crimes whether the victim was Muslim or not. I bring this up because William Dalrymple has an op-ed in the NY Times about the proposed Islamic center planned for lower Manhattan (for those living under a rock, see William Saletan’s piece in Slate for a good roundup of the issues surrounding the center):

The problem with such claims goes far beyond the fate of a mosque in downtown Manhattan. They show a dangerously inadequate understanding of the many divisions, complexities and nuances within the Islamic world — a failure that hugely hampers Western efforts to fight violent Islamic extremism and to reconcile Americans with peaceful adherents of the world’s second-largest religion. Most of us are perfectly capable of making distinctions within the Christian world. The fact that someone is a Boston Roman Catholic doesn’t mean he’s in league with Irish Republican Army bomb makers, just as not all Orthodox Christians have ties to Serbian war criminals or Southern Baptists to the murderers of abortion doctors. Yet many of our leaders have a tendency to see the Islamic world as a single, terrifying monolith.

Dalrymple’s main point is that the Sufis behind the Cordoba Initiative are themselves “infidel-loving, grave-worshiping apostate[s]” in the eyes of the Taliban and Osama bin Laden. We’ve been here before:

In 2006, the investigative reporter Jeff Stein concluded a series of interviews with senior US counterterrorism officials by asking the same simple question: “Do you know the difference between a Sunni and a Shia?” He was startled by the responses. “One’s in one location, another’s in another location,” said Congressman Terry Everett, a member of the House intelligence committee, before conceding: “No, to be honest with you, I don’t know.” When Stein asked Congressman Silvestre Reyes, chair of the House intelligence committee, whether al-Qaeda was Sunni or Shia, he answered: “Predominantly – probably Shia.”

Clearly the United States would be better off if our leaders, journalists, and citizens knew a little more about Islam. But there are also some lessons here about the semiotics of racism which I would like to think offer some insights beyond the 24 hour news cycle.

A Liverpool working-class accent will strike a Chicagoan primarily as being British, a Glaswegian as being English, an English southerner as being northern, an English northerner as being Liverpudlian, and a Liverpudlian as being working class. The closer we get to home, the more refined are our perceptions.

The above quote is taken from a discussion in Asif Agha’s masterful book Language and Social Relations. Agha’s focus here is on the limits of of performativity. By pointing out that the hearer’s own prior socialization provides an important context for the successful performance of identity, Agha sets the stage for one of the book’s central themes: that identity is not only mediated by discourse, but also requires a process of negotiation between speaker and hearer—and that this process of negotiation can be transformative, changing the possible range of identity positions available to both parties as well as society at large.

I quite like Agha’s argument, and in chapter after chapter he makes a convincing case for it. Particularly interesting is his discussion of kinship terms, in which he shows how a mother might refer to her in-laws using terms which, taken literally, would place her in the role of her own child vis-a-vis her relatives, but are nonetheless lexically differentiated from the terms a child might use. In doing so she claims her rights as the mother of the child without reducing herself to the status of a child.

While the discussion of a Liverpool working-class accent shows that Agha is aware of the limits to such performativity, I would have liked to see more discussion about situations where one party refuses to negotiate. Agha’s approach to limits implies that performativity might fail because of one party’s lack of socialization, but what about if one party has a will to ignorance? I think such willful ignorance is behind much American confusion with regard to Muslims, and so I’m not sure how much use historical, ethnographic, or journalistic accounts of the various divisions within Islam can help.

It seems to me that part of the problem derives from the very idea of a “just war.” As Judith Butler argues, such a concept requires the “division of the globe into grievable and ungrievable lives from the perspective of those who wage war.” For some section of humanity to remain “ungrievable” requires a willful ignorance which refuses to engage in the kind of dialog which would allow for negotiated meanings to emerge. Thus, Islamophobia is in some ways a prerequisite for waging a global war on Terror, even as our leaders insist otherwise.