[Savage Minds welcomes guest blogger Sara Perry.]

This is the first in a series of posts, coordinated with Colleen Morgan, on the relations between analog and digital cultures. Over the next month, through the contributions of a variety of archaeologists, we will explore the concept of materiality in an age where the nature of ‘the material’ is rapidly shifting. How do physical materials and digital materials shape one another? How does experimentation with the digital rethink the dimensions of the analog, and vice versa? How, if at all, do we distinguish between one and the other – and is this even necessary (or possible) today? How have our understandings of ‘the real’ – of ‘things’ and ‘facts’ – of presence and the body – of aura and authenticity – been shifted by interactions between physical and digital materials?

As the premiere scholars of materiality, archaeologists are well-versed in the continuities between, and changes to, artifacts. Here, we probe their boundaries through discussion of our engagements at the intersections of the analog and the digital. I begin with some critical comments on mobile apps: oft enrolled in visitor experiences at archaeology and heritage sites, are these digital tools actually valuable?

I’ve been working at the convergence point of analog and digital technologies for many years now. This entails studying how archaeologists deploy them in their professional practices, training others (and myself) in the use of digital tools to facilitate better understanding of the archaeological (physical) world, and creating opportunities to expose crossovers between analog and digital environments (for example, developing virtual exhibitions displayed in physical spaces).

Most recently, I’ve become concerned with mobile apps. In archaeology – and in the museums world – these kinds of hand-held technologies have a long history of use, particularly for delivering interpretation of artefacts, exhibits, and full sites to visitors (e.g., see Jeater’s review). A project or an institution may develop an app that you download on-location or beforehand, which then typically acts as a form of guide around the place and its collections.

My interest is in the link between these mobile technologies and the material world. In the best case (e.g., see the work of Eve, Hoffman, Morgan, Pantos and Kinchin-Smith, produced as part of the Heritage Jam), they are means to full multi-sensory experiences of ancient landscapes.

But in the worst case, they have little or no physical relevance, in the sense that they could just as easily (or more easily) be used in the home, while still in bed, rather than out in a mobile landscape.

If you’ve tested out a few apps for heritage sites, you’ll likely identify with this predicament. Their real possibilities are often not being exploited (e.g., the opportunity to physically move around different locations), and when they are (e.g., in the case of augmented reality apps), it’s unclear who’s using them, how meaningful they really are for visitors’ appreciation of the archaeological record, and what bigger impact they are having on relevant fields of practice (e.g., how they are really altering heritage interpretation? Is it worth it?). If sound is deployed on the app, it regularly works as little more than a surrogate tour guide.

When using heritage apps, you often spend much your time staring at the screen of your mobile device, reading text or viewing visual materials on the device itself to the detriment of the site you’ve come to see. Some recent testing we’ve done in York has even suggested that apps falsely lead users to feel that they’ve visited ‘everything’, when in fact they’ve visited only a fraction of what non-users experienced.

Many people also seem inclined to develop apps that reinforce these problems: they are standard, unexperimental, grounded in the typical hand-held audio guides that were the ‘mobile apps’ of 50+ years ago (e.g., in museums).

Developers often talk about the positive aspects of mobile apps, especially their potential to attract new and younger audiences, their promise of immersion or embodied experience, their entertainment value and heightened relevance in the modern world. Others have highlighted their negatives, which as I’ve noted above, can seemingly be infinite, e.g.:

- distracting visitors from the actual site itself

- isolating visitors from their companions

- isolating artifacts from one another

- can be expensive to develop

- memory limits on mobile device may make downloading or use of the app impossible

- app may have an additional costs for users including expense for connecting to mobile signals

- persistent digital divides might make apps inaccessible to significant demographics, and reinforce structural inequalities

Despite all the negatives (and I can go on, as not only do I teach mobile app development, but a number of my students are studying the efficacy of existing heritage apps), I still find them compelling. I’m drawn to them because I believe they have so many under-exploited possibilities that might have transformative effects on how we interpret the archaeological record and on how we interact with other interested people.

If done well, I believe such technologies can perform a critical role in enabling their users (and makers) to think through the complex relations between space, place, humans & media. Mobile devices are ubiquitous in many parts of the world, and in some of the developing contexts that I’ve been working recently (e.g., Egypt), they are an essential part of all aspects of everyday life, yet are rarely used in the context of heritage. They allow integration of multiple types of rich media (still & moving imagery, sound, etc.). And, as I see it, they are still in their experimental phases, so there is much room for innovation, and – as they have not yet been fully institutionalised – there is still real flexibility to push on their boundaries.

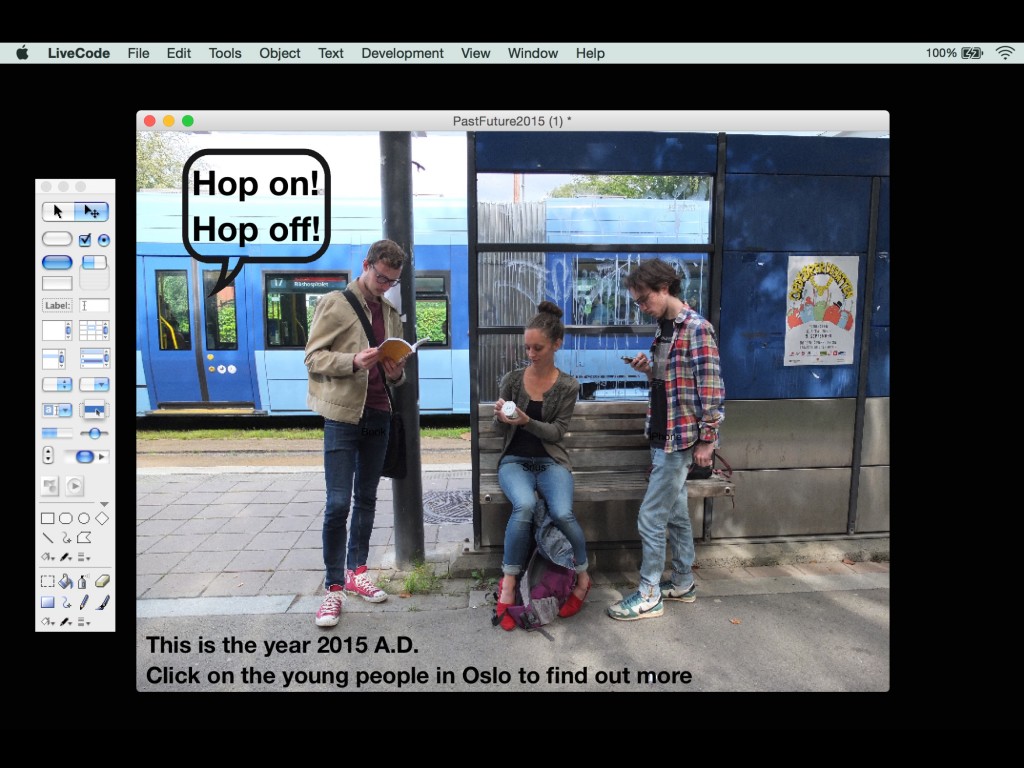

For such reasons, and in collaboration with multiple teams, I’ve been experimenting with mobile app development in various environments. This includes the making of low-tech, open access/open source apps crafted and conceived by students (thanks to Tom Smith for all his support!). It also includes larger scale initiatives, for instance at the world-renowned Neolithic site of Çatalhöyük in Turkey.

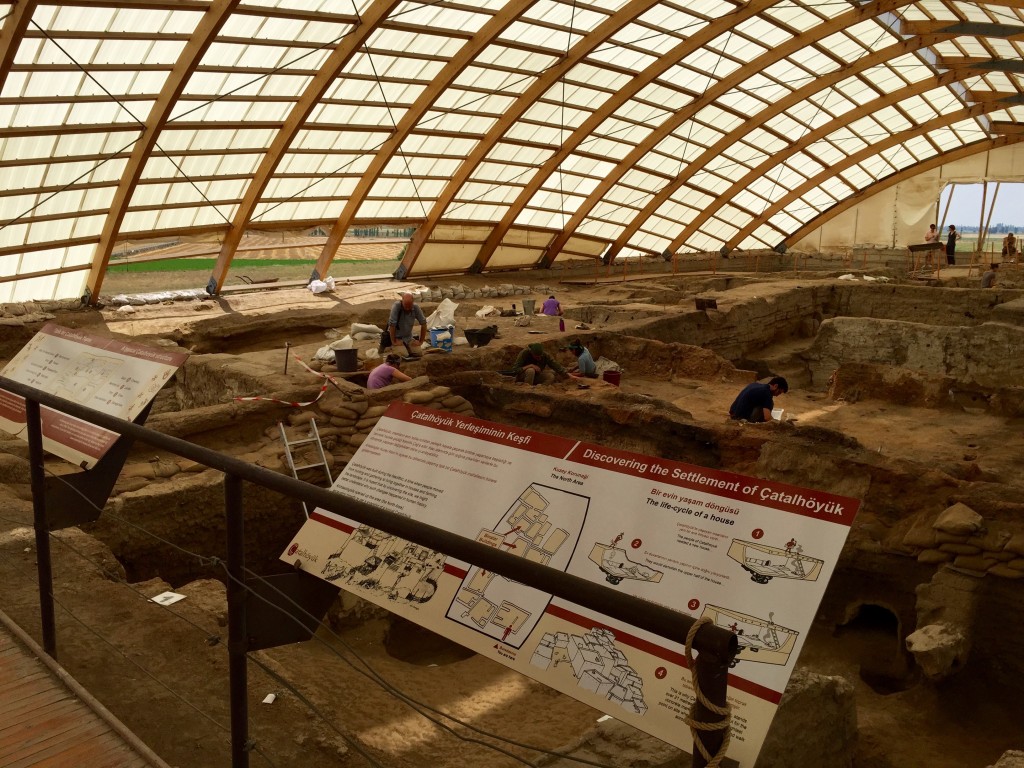

At Çatalhöyük, over the past 7 years and in partnership with students and colleagues from the universities of Ege, York and Southampton), I have led many of the site’s heritage interpretation ventures (e.g., curation of its Visitor Centre, development of on-site signage, production of the site’s guidebook, maps and brochures, etc.), including evaluation of visitor experience. (For more info on our activities, see the “Visualisation Team” section of Çatalhöyük’s Archive Reports).

Here, we have developed a very thorough understanding of tourist expectations (as a relatively remote site, it still sees upwards of 20,000 visitors per year). And we have the opportunity, through the support of the Project Director Prof Ian Hodder, to experiment on a large scale with digital/analog interventions, with great potential to impact not just visitor experience, but also professional practice (given Çatalhöyük’s visibility in academic archaeology).

Çatalhöyük is an important case study for many reasons:

- The nature of its mud-brick architecture combined with the dusty environment make it difficult for non-specialists to perceive the archaeological record.

- Despite our efforts, there are still relatively few interpretative materials on site, and those that do exist are often not maintained.

- Difficult weather (hot in summers, cold in winters) and technological conditions make visiting and presenting the site challenging; and Çatalhöyük is in a remote location with problematic public transport options.

- Only a small number of knowledgeable people are available on site to communicate additional information to visitors on a year-round basis; virtually no archaeologists are present outside of summer months.

- Inflexible touring schedule/approach, often with poor instructions and rigid route, handcuff the visitor experience; indeed, visitors have been observed to actually jump illicitly into excavation units in order to get closer to the archaeology, yet even then they still might leave with limited appreciation of the site.

- Because many visitors do a lot of research about the site before coming to see it, when they arrive they tend to understand more about it. Visitors often also seek out supplementary informational resources, plus they regularly come to site with mobile devices & are willing to use those devices on site. This presents a tremendous opportunity for us, because given that visitors are doing such pre-visit research and are prepared to use their mobiles, it means we can potentially cater to them with technological options delivered in advance of their visit.

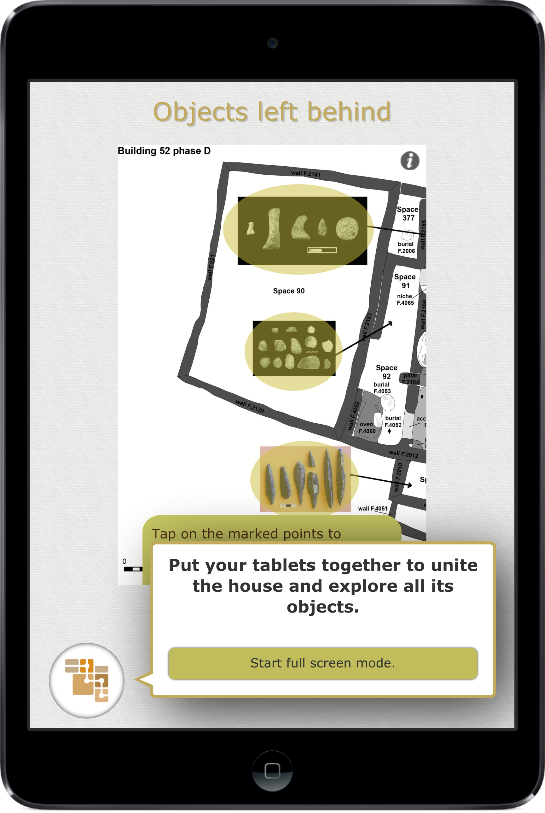

Funded through the the British Institute at Ankara (BIAA), and in partnership with the CHESS team, in 2014 we began to experiment with this opportunity. In the first instance, we constructed a mobile device-based narrative about a particular building at Çatalhöyük (Building 52), written by the site’s own experts, populated with existing visuals and audio recorded by the authors of the story. Our evaluations of the app suggested that its real impact was actually on the archaeologists themselves who crafted the narrative. In other words, their involvement in writing the content of the app affected how they thought about the site and their research at the site (Roussou et al. 2015). Experience of use of the app itself for understanding the archaeological record, however, was mixed.

In Summer 2015, with further funding from the BIAA, and again in partnership with CHESS, we returned to site to elaborate the app. This time, however, we wanted to push back against some of the problematic trends that we’ve observed with these tools, and maximise the capacities of the mobile device – its social functions, its multi-media possibilities, its portability – to create connectivity. Our aim was to use the app not simply to communicate a story about Çatalhöyük, but to:

(1) facilitate engagement between visitors on site (both people in the same tour group and other unknown people touring the site), and

(2) engage users’ bodies and prompt interactivity with the physical world around them at the site

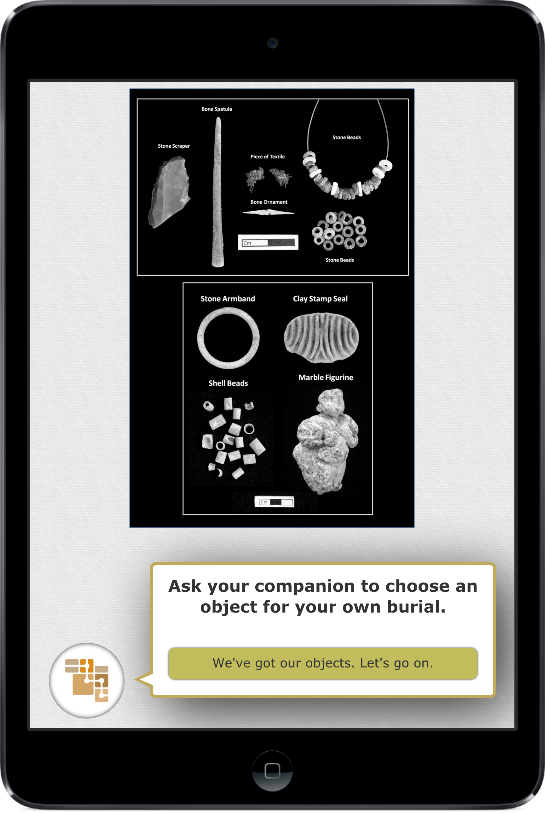

To do this, we split the existing script for the app (created in 2014) into multiple parts so that two members of a visiting group had to work together to understand the storyline. In other words, each person would only hear/see a fragment of the story, and it would only be via (prompted) conversation between the two of them that the full narrative would become evident. We added even more prompts to various parts of the story in an effort to compel discussion, reflection and collaborative decision-making about past inhabitants and activities in Building 52. We worked to augment the haptic nature of the experience of holding/looking at the mobile device by asking users to touch and align their devices. This created a kind of ‘shared screen’ for visitors, pulling the content on their individual devices into a larger whole – something which they could subsequently explore together. We also attempted to add playfulness to the experience, for instance, prompting users to choose particular items excavated from the house to virtually ‘give’ to their partners.

Our efforts were rolled out through a multi-stranded approach.

Firstly, we conducted a ‘body storming’ session at Çatalhöyük with researchers at the site, specifically aimed at thinking through how we might better engage the body in the interpretative experience at Çatalhöyük. Participants in the session were asked to articulate, then act out (without words), concepts associated with being a ‘Çatalhöyükian’ – and what ‘Çatalhöyükness’ meant to them. The idea was to be able to use the embodied results of this session to inform new content and experiences for the app. However, while full analysis of the session is forthcoming, initial interview results provided mixed feedback on its utility.

Secondly, we tested a prototype of the app on site in July with an audience of researchers and students. Evaluated through interview and video capture (see Katifori et al. 2016), the results again were mixed, but with more sense of promise: some users liked the interactivity we’d added, some did not; some felt they were being ‘cheated’ by having to ask their visiting companion for information (rather than learning direct from their own device), others felt clearly more engaged with the site. Everyone, however, appeared to enjoy the playful elements added to the app. A full description of our work will be presented at the next Museums and the Web conference in Los Angeles this April.

Thirdly, with my team of students from Ege University and the University of York, we installed on site a separate, physical display – meant as a point of comparison to the digital display of the app. In this case, we used Çatalhöyük’s replica house as a hiding place for a number of printed plexi signs. Each sign provided a clue to locating the next sign, with the aim of encouraging visitors to actually engage with the physical parts of the house – its oven, baskets, storage rooms, etc. Initial assessment suggests that these signs have been successful in encouraging touch, movement, material and bodily interactivity – more than I’ve typically seen with mobile apps.

Possibly the most interesting component of all of this work for me has been its evaluation, and the passionate reactions expressed by many – particularly to the mobile app. We’ve only just begun to review the interview data collected from users of the app, but my impression is that it’s generated a polarised set of replies. These range from true advocates who felt genuinely influenced by the experience, to those who perceived it as a waste of time, or as something too radical, or gimmicky, or distracting from the experience of ‘being there’.

Personally, I continue to feel conflicted about mobile technologies for heritage interpretation. I’m not convinced that we’ve yet untangled the means to blend the physical and the (handheld) digital into a complementary visitor experience. But ‘being there’ at a place like Çatalhöyük is very complicated (for reasons that include everything from transport and infrastructure to the fragmentary nature of the archaeological record), and these technologies do have affordances that could ease – perhaps even eliminate – such complications. I’d like to think that one day this will be possible.

So I’ll sign off now with a series of questions that I continue to grapple with, and that will present themselves in different forms in some of our other posts over the course of this month:

What are digital technologies actually enabling, if anything? Does the traditional analog equivalent (in my case, a printed sign) still offer more to users?

How can we deploy digital technologies (for example, mobile apps for cultural sites) in more productive, bodily- and thought-provoking fashion?

And from the archaeological perspective,

How can we improve people’s experience and understanding of the archaeological record? For instance, if developing a mobile app, how can that app create a more impactful tour of a site for visitors, more human-to-human interaction on the tour, and a richer sense of one’s own presence there at the site – in the moment – and in the past (as a Çatalhöyükian)?

Sara, thanks for putting this series together. Great stuff. I am looking forward to reading the posts.

You have undoubtedly thought of this already. The first thing that popped into my mind would be an app that combines images captured with the device’s camera with overlays that enhance the experience of seeing what is on the ground. I think of my wife’s fascination with Google maps that enable here to superimpose old maps on current topography to trace changes in the landscape of the city and neighborhood in which we live. Having seen the terra cotta warriors in China, I can imagine an overlay whose perspective would change as I moved around and highlight items of particular interest.

Just brainstorming.

Yes, thanks so much John! Like many, we’ve been looking at these kinds of options, which depend on a variety of factors, including available imagery, access to graphic designers or visual specialists, cost, etc. There are some incredible projects, for example, by folks like Stuart Eve, which have aimed not only to integrate imagery but smell too! (e.g., see http://www.augmentedrealitytrends.com/augmented-reality/dead-mens-nose.html) In the end, I still have a lot of doubts about the utility, accessibility and sustainability of these tools (my own included). But I do think it’s still relatively early days in terms of their development for general audiences, so we’ll see… So many thanks again for your comment & ideas!

Imagine an app that, when you turn it on, presents the message, “First, stop for a moment. Put down your device, and look around you. Overlays will become available five minutes from now.” (Experimentation will be needed to see how much delay people are willing to tolerate.)

I would say that the benefit of digital over analog is that there is the potential for an unlimited supply of information, even with limited space, however challenges of engagement with physical subjects would be no different than they have been with analog information sources. For example, the nose to the screen is the same as the nose to a paper map, wherein both might lead to walking past an ‘important’ marker. Ultimately it seems as though perception control is what one would be after for an exhibit—control how the participant views subject and observes info about subject to convey decided meaning of subject—or in your case, following a narrative and going on a journey through that narrative. If that is the case, it might be beneficial to talk to some advertising and marketing people about how best to design an app in conjunction with the exhibit for maximum engagement through perception control. Someone who develops brands would be equipped to figure out how to get people to widely accept a particular message or meaning.

Thanks so much for your thoughts, Glenn. In many ways, we want to cultivate freedom of perception, but control of expectations around the delivery of the overall experience. This is perhaps the most challenging part, because one might argue that people tend to visit these sites already anticipating not just what they’ll perceive but how they’re meant to perceive (and otherwise physically engage eiyh) them. Like you say, any medium (analog or digital) impacts this experience. Some of the testing we’ve done suggests digital tools are narrowing the experience even further, when one might have anticipated – or hoped! – the opposite would happen. We work very closely with a range of designers (graphic designers, interaction designers, etc.). I do like the idea, though, of expanding that team to include branding experts. I think this offers food for thought on multiple levels.

Map overlays allow visitors to switch back and forth between modern and 9th century Kyoto. Just stumbled across this and thought it might be interesting.

http://en.rocketnews24.com/2016/01/08/interactive-online-map-of-kyoto-lets-you-toggle-between-modern-day-and-the-9th-century/