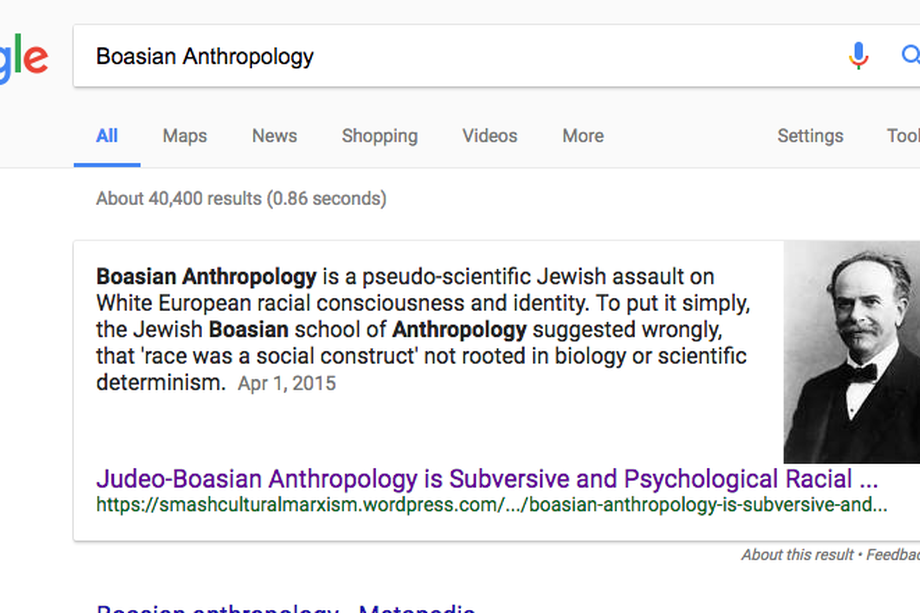

Various bits of social media began vibrating rapidly recently when it was discovered that white supremacists had fooled Google into providing inaccurate information about Boas and cultural relativism. The situation is now apparently resolved, but it isn’t a new problem. Old-timey internet veterans will remember that martinlutherking.org has been run by Stormfront for, like, decades. But this latest kerfuffle should give us the opportunity to think about our priorities as anthropologists writing for the general public today. In a previous post, I argued that there is a difference between the older ‘heroic’ public anthropology and ‘new’, more important public anthropology. Today I want to expand on this point and emphasize that we need shift our conception of public anthropology away from older, moribund genres and to newer, more important, but less familiar ways of reaching the public.

Let’s start with the old school approach. This older, more ‘heroic’ anthropology feels glamorous to the people who do it. It feels like you’re Margaret Mead (a good thing, apparently). You feel personally responsibility for changing the world. It consists of writing in established genres that feel important to you. But it actually does not matter very much. For instance: Letters to the New York Times. How many times have I heard anthropologists moot how to get a letter published in the New York Times so as to correct or refute something they had read online? Too many. Too. Many.

I’d argue that these letters to the editor do almost nothing to educate or persuade. I honestly think few people read them. Also, they are short (<200 words afaik). Not only do you not have enough space to say thing, but you are preaching to the converted. Honestly: did the affluent liberal readership of the times not already know that race was skin deep or Donald Trump needed to be stopped? No one is learning anything or having their minds changed. But hey: YOU GOT A LETTER IN THE NEW TORK TIMES GO TELL TEH OTHER PROFESSORZ.

I have tremendous respect for the Times and the original reporting it does. My issue isn’t with that paper, or really any paper. Rather, my issue is that anthropologists are doing public anthropology in the wrong places and in the wrong way because they don’t understand how social media works today and are seduced by an out-moded model of cultural capital that makes them feels heroic, but it isn’t actually efficacious.

The new public anthropology, on the other hand, is not glamorous, will not make you famous, can be emotionally uncomfortable, involves working in new and unfamiliar genres, and can change the world. A good example of this sort of public anthropology is editing Wikipedia

Wikipedia is ground zero for knowledge in the world today. Everyone uses it to look stuff up quickly. Everyone. Some people may take it more seriously than others, but because its content can be reused on other sites, what wikipedia says spreads everywhere. For better or for worse — I’d say for better — it’s the public record of the state of human knowledge at the moment. Unlike letters to the New York Times, Wikipedia gets read. Constantly. When you contribute to Wikipedia, you are concretely and immediately altering what the world knows about your topic of expertise.

As long time editors of Wikipedia know, editing pages on Boas, race, and other topics is like trench warfare. Years of battles to defend inches of territory have seen wikipedians engage deeply with a body of work which is both racist, theoretically shoddy, and empirically inadequate. But if we do not keep contributing to wikipedia, then we cannot complain when google search results for Boas start showing up with this sort of twaddle in it.

Professors today are disconcerted to learn that Twitter is a place where professors are disconcerted to learn that no one automatically takes them seriously because they are the Endowed Chair of This and That at the University of Thus and Such. Editing wikipedia is equally unglamorous. Its a place where your authority and expertise are questioned. It will not reaffirm your sense of yourself as an expert. In fact, this is a genre that many academics will find unfamiliar. Not only do you have to learn the mechanics of editing, but Wikipedia’s emerging common law of editorial standards will be unfamiliar. But in the end it is worth it, because what you write will be read. You will reach new audiences and spread your scholarly expertise far and wide.

Wikipedia is just one site where new public anthropology can happen. It could happen on Twitter, or Medium, or Facebook, or Quora, or in a review for Amazon. This new, important, efficacious public anthropology has the power to inform, convince, and persuade. But its not what we’re used to. Anthropologists need to stop leaning on their titles and claims to expertise. Instead, they need to start making expert claims. Moving from a heroic, ineffective public anthropology to new and unfamiliar genres will be key to making sure that everyone, everywhere, has access to the factual and accurate information they need in this troubling new time.

I am a fan of your ultimate message, but I have some misgivings about your confrontational and dismissive tone. I’m curious… Why can’t public anthropology be BOTH writing letters to the NYT and other “traditional” publications AND working in digital venues with a far broader and quicker readership? What ever happened to “all of the above” solutions? Or are we going to limit ourselves like much of the 21st-century American public has, asking “what thing should I care about to the exclusion of all others this week?” If we are really concerned about public anthropology, we need to reach as much of that public as possible, and that’s likely to mean walking and chewing gum at the same time (and not assuming that everyone is using or able to access social media).

Thanks Will. It’s a fair point.

Thanks for this — I think it is so very important to get more Public Anthropologists into the Wiki-world and have them climb the ladder of authority within that framework.

Another great wiki idea is to set up edit-a-thons or meetups for wikipedia to enter into the archive people/events/things that fall out of the algorithm of notability.

So for example, last year, for a course, I joined my collaborator and class to develop an Edit-a-Thon/Meet-up Project – and it was used again this year to continue the project called ART + COMMUNITY.

“ART + COMMUNITY is an edit-a-thon project developed in the Art, Culture, and Community Development Course (SS-512) in the Social Science and Cultural Studies Department at Pratt Institute in Brooklyn, New York. During this edit-a-thon we will be submitting pages for artists, activists, and organizers with a sustained involvement in cultural production, community building, and intersectional dialogs.”

To those interested, you can check out:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wikipedia:Meetup/ArtAndCommunity

Thanks so much for bringing this up – so very important to talk about new and diverse ways to engage with the contemporary world. And I have to say, when academics claim they have made a public intervention by writing a letter in the NYT, I do roll my eyes. Sure – public anthro can walk and chew gum – but if the goal is to get out of a burning building, I would concentrate on ambulation rather than mastication. Also – just a quick HT to my fave line in this “The new public anthropology, on the other hand, is not glamorous, will not make you famous, can be emotionally uncomfortable, involves working in new and unfamiliar genres, and can change the world.”

Thank you.

For last years’ MeetUp Info, see: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wikipedia:Meetup/ArtAndCommunity/Brooklyn2015

I had a history and women’s studies prof in undergrad who, for the final paper, would assign each student to pick a Wikipedia entry on a topic of historical significance and edit it, focusing esp on adding information, sources, and critical readings that reinserted women and people of color into historical narratives that privileged the words and experiences of white men. I always thought that was an awesome assignment, and a good way to combine public scholarship and pedagogy.

I made this same point in AA a couple of months ago. http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/aman.12598/full

Also, a demonstraiton is the fact that I was able to cause the White Supremacist definition of “Boasian Anthropology” to drop down in the google results simply by creating an article on Wikipedia about “Boasian Anthropoloyg” – the thing is that google privileges wikipedia, but in this case Wikipedia didn’t have an article on the topic!

For those who seriously consider Rex’s call to action, I recommend this ethnography of Wikipedia editing:

Jemielniak, D., 2014. Common Knowledge?: An Ethnography of Wikipedia. Stanford University Press, Stanford, California.

There’s useful stuff on edit wars, dispute resolution mechanisms, and the model of procedural objectivity that is favored in its “edit culture”.