[Savage Minds is pleased to run this essay by guest author Yarimar Bonilla as part of our Writer’s Workshop Series. Yarimar is Assistant Professor of Anthropology and Caribbean Studies at Rutgers University. She is the author of Non-Sovereign Futures: French Caribbean Politics in the Wake of Disenchantment (University of Chicago Press, forthcoming Fall 2015) and has written broadly about social movements, historical imaginaries, and questions of sovereignty in the Caribbean. She is currently a fellow in the History Design Studio at Harvard University where she is working on a digital project entitled “Visualizing Sovereignty.”]

In a recent contribution to this writers’ series, Michael Lambek offered some reflections on the virtues of “slow reading.” In an era of rapid-fire online communication, when images increasingly substitute for text, Lambek argues we would be well served to revel in the quiet interiority and reflective subjectivity made possible by long-form reading.

In this post I would like to think more carefully about this claim and to consider whether we might want to make a similar argument regarding the shifting pace of academic writing. If, as Lambek and others suggest, the temporality of reading has been altered by the digital age, can the same be said for research and writing? How have new digital tools, platforms, and shifts in technological access transformed the temporality of ethnographic writing, and is this something we necessarily wish to slow down?

I recently had occasion to experiment with sped-up academic pacing when offered the opportunity to contribute a piece to American Ethnologist about the protests surrounding the killing of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri. In brainstorming our article, my co-author Jonathan Rosa and I asked ourselves hard questions about what we could contribute to the unfolding discussion about Ferguson. Both of us had produced academic “slow writing”— the product of years of careful research, analysis, drafting and editing. We had also engaged in some forms of “fast writing.” For example, I had published journalistic pieces on social movements in Puerto Rico and Guadeloupe. But these pieces focused on events not being covered in the mainstream media and for which informed journalism was necessary. The same could not be said of Ferguson. Despite an initial lag in journalistic coverage, by the time we were drafting our article, Ferguson had reached a point of media saturation, indeed it had become a challenge to keep apace with the numerous thought pieces and editorial columns emerging at a feverish pace during this time.

Image from the Ferguson newsletter

In plotting our article we thus asked ourselves: how can we contribute to this fast moving conversation while still producing a piece that might hold up over time? That is, how could we produce something fast but not ephemeral?

The result was an exercise in mid-tempo research and writing. It was not the product of long-sustained fieldwork, and was very much written “in the heat of the moment,” but it nonetheless tried to anticipate how anthropologists might look back on Ferguson over time—how they might use this event to teach and write about broader issues of racialization, longer histories of race-based violence, the racial politics of social media, and the shifting terrain of contemporary activism.

This process forced us to think about the challenges of being not just fast writers but fast ethnographers. How can we speak to fast moving stories while still retaining the contextualization, historical perspective, and attention to individual experiences characteristic of a fieldworker? Also, how can we engage with emerging digital platforms like Twitter with the comparative and ethnographic perspective characteristic of our discipline?

The latter requires us to take seriously the narrative genres and political possibilities afforded by new forms of digital communication without assuming that their speed robs them of their social complexity. For example, while some might see the prevalence of “memes” and the seeming dominance of image over text on the internet as an inherently negative development, as anthropologists we are well poised to recognize that shifts in communicative practices are neither inherently virtuous nor corrosive. Rather, they speak to, and are themselves generative of, a new set of social and political possibilities.

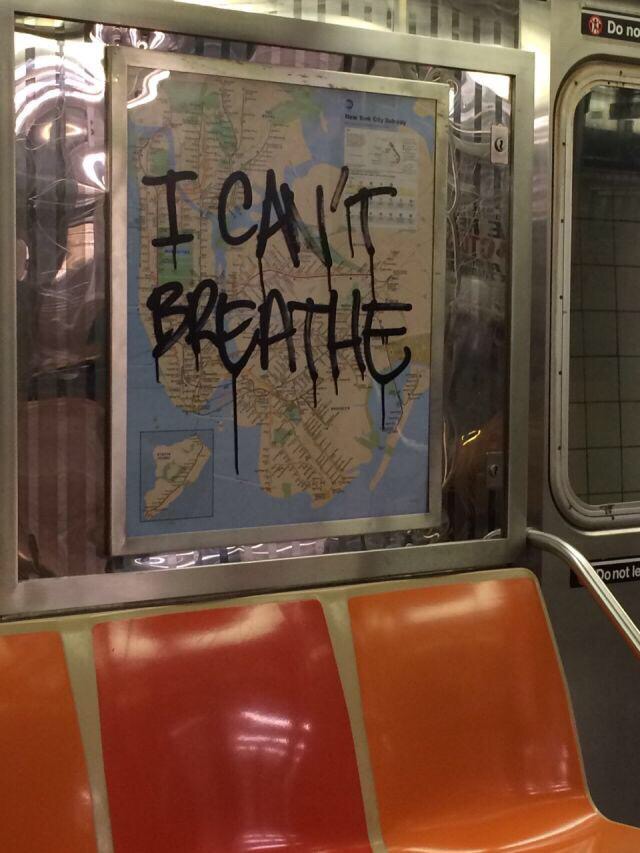

Photograph from the Ferguson newsletter

In the case of Ferguson, the fast-moving pace and ease-of-access afforded by Twitter helped activists and supporters bring heightened awareness to what would have otherwise been an under-reported story. Moreover, it allowed many individual users for whom slow writing is not a possibility or a desired practice, to engage in forms of creative expression and reflective activity that could challenge, contest, and contextualize mainstream print narratives in which they rarely see themselves adequately represented. The tweets, images, memes, and hashtags that circulated during this time (and which continue to circulate) should thus not be seen as cheap and fast substitutes for artisanally crafted modes of personal reflection. Instead, they need to be understood as complex texts, worthy of the same kind of close-reading and critical analysis scholars usually devote to long-form prose.

Ethnography in the digital age requires us to avoid conflating the fast with the ephemeral or the vacuous. The aggregative and cumulative dimensions of social media, as well as their far-reaching scope, force us to re-think what constitutes an enduring or transformative social action. Moreover, attention to these practices also requires us to think more carefully about how we, as academic writers, can contribute to fast moving conversations without giving short shrift to the historical and analytical contextualization that is often absent in quick moving public debate. These challenges require us to move quickly when we feel something is worth attending to while still rallying in those quick moments the kind of critical perspectives that can only be honed slowly, accumulatively, over time.

Clearly it is not a case of either/0r: we need slow and fast reading, fast and slow writing. I have long thought that the New Journalism movement of the ’60s and ’70s, in which an ethnographic approach had to be directed more proximally and achieved more rapidly because of deadlines contributed a a great deal to ethnography way before the somewhat retarded and strangely named ‘Crisis of Representation’.

Thanks for your comment! I agree, the challenge is precisely to think about the different temporal possibilities. Thus, it is less about speeding up or slowing down than about figuring out the appropriate pace for the conversation at hand…