[The post below was contributed by guest blogger Ali Kenner, and is part of a series on the relationship between academic precarity and the production of ethnography, introduced here. Read Ali’s prior posts: post 1 & post 2]

In this post I’m going to diverge a bit, writing not about my work for Cultural Anthropology, but about that other project of mine: an ethnography of breathing, and how the breath registers embodied signs of late capitalism (in the contemporary asthma epidemic and U.S. yoga industry). It’s a project grounded in my own yoga practice, a risky set-up, I think, for someone already working on the margins.

Deepa’s weekly prompt asks us about the relationship between form and content in our work. This prompt called to mind the way I position myself to my project, leveraging embodied practice for ethnography. Rereading Carole McGranahan’s post on teaching ethnography, I keep coming back to Ortner’s understanding of ethnography as “the attempt to understand another life world using the self—as much of it as possible—as the instrument of knowing.” Tomie Hahn’s ethnography of dance transmission, Sensational Knowledge (2007), is a powerful example of how body and self become instruments of knowing. Working in the Japanese tradition of nihon buyo, Hahn shows how cultural knowledge is embodied through her own experience and practice of nihon buyo, a practice sustained over three decades. What I find most interesting about Hahn’s work is the way she translates movement and sensation into graspable material for analysis. The argument that culture flows through dance transmission is performed back to readers through Hahn’s own transmission; thick descriptions of sight, sound, and touch.

Hahn also speaks to the challenges and drawbacks of embodied ethnography – studying her own culture, wearing various hats, and negotiating multiple identities. Although my project, and my relationship to it, is quite different from Hahn’s, Sensational Knowledge is an enduring touchstone that inspires my work. It’s important to have one or a few of those in reach.

In the sections that follow I put yoga in conversation with ethnography. In the first section, breathing becomes an instrument of knowing; in the second, I consider how my yoga practice situates me as ethnographer.

BREATHING ALTITUDE

Just about every morning, at about the same time, I start the day with a series of meditations that involve pranayama, a yogic breathing practice. There are dozens of breathing exercises to choose from, perhaps even hundreds. In the Kundalini tradition, breath is measured by mantra, a rhythmic repetition of sounds. Practice a particular meditation every day for three months (or for three years, as the case may be) and you will begin to notice things – how far you can pull your belly button back towards your spine, where you overworked your body the day before, the difference between sleepy and exhausted, and of course, the quality of your breath. You will also notice your surroundings, like the early morning smell of businesses down the hill and what time your neighbors leave for work and school. With a consistent daily practice you may begin to associate disparate observations, drawing tentative causal relationships between body and environment. On nights when I eat ice cream before bed, for example, I find I’m more congested in the morning, my breath shallow.

Daily pranayama will make you more attuned to air quality. The difference between the high desert of Northern New Mexico and the guest bedroom of a Woods Hole cottage is striking, as I discovered in my travels last month. The New Mexico air dries you out to the extent that your breath stops short, an involuntary visceral measure to protect the nasal passages. On the coast of Massachusetts, on the other hand, the air is so thick with matter you can’t get the oxygen you need. Although the length and depth of my inhale was the same, the air felt like mud, sticking to my air passages, reducing the flow of breath. It’s one thing to know this from looking at EPA generated maps or by talking with environmental engineers. It’s another to know air quality in your body.

The high desert of New Mexico and the Southern coast of Massachusetts make for a fascinating climate contrast. Experiencing these two extremes back to back gave me embodied insight into how air quality matters for those with breathing disorders, like asthma. Most asthmatics I talk to reference their environment a lot – dust, mold, humidity, pollen, temperature. That’s a good sign since asthma care today is as much about avoiding environmental triggers as it is using an inhaler. Attuning to sensation in environmental context is critical for asthmatics. It’s also knowledge gained over time, by living in the body and paying close attention when the body is talking at you, or screaming, as the case may be. This is a tall order when you’re fighting to breath.

Most of us are not fighting to breathe. Most of us are not even conscious we’re breathing. How many times a day do you say to yourself, “Hey, look at me! I’m breathing!” But there are many people (asthmatics and yoga practitioners are two prominent, contrasted, examples) who are very aware of their breath, albeit for different reasons, in different contexts. Analysis of breathing in the U.S. today reveals a lot about class, race, and gender; health assemblages and environmental imaginaries; late industrial culture, and its hoped for cure. This analysis is made using my breath – as a vehicle that provides access to sensations and situations; as a space for reflection and analysis; and as a constant medium that gives firm ground to stand on. Asthmatics do not get this kind of stability from the breath – for asthmatics, breathing can be the ultimate form of precarity.

As described above, sadhana, a daily yoga practice grounded in the breath, provides the kind of long-term relationship I’d like to have as an ethnographer. Exactly the kind of relationship that is so difficult to maintain in the contemporary academy.

FIGURING OUT ALIGNMENT

The first time I found myself noticing alignment I was standing in line waiting to board a flight home from New Mexico. When the man in front of me set his bag down, rolled his neck, and then stood at attention, I noticed his shoulders – his right shoulder rose about two inches above his left, the scapula bulging to a degree unmatched on the other side. Moving my gaze down to his hips, I could not detect further asymmetry (ultimately due to my lack of training and the man’s clothing), but it would undoubtedly be there – misalignment in one sector of the body indicates misalignment in other areas. The hips and shoulders are like roommates in a dorm, proximity matters; the state of one will impact the state of the other. Of course, surface analysis is never sufficient. If you’ve got shoulder problems, it’s probably effect that should be read as sign. Referent is a bit trickier to track down. This I learned from my own misaligned, pained, body, and the bodyworkers and yoga teachers who I’ve studied with over the past four years. Time spent with my dear friend and teacher Tanya Zayhowski, for example, taught me volumes about structure, freeplay, and history. Our lessons always took place around a yoga mat.

In the Albuquerque airport, I found myself wanting to strike up a conversation with the man in front of me, hoping that I could somehow tell him his alignment was off. I remember being at once horrified and curious – amused by my observation of a stranger’s structure (clearly, my yoga practice and training was cultivating a new kind of sensibility), and concerned by my desire to do something with that observation. Here is a moment where “critical distance” would be most useful (see Deepa’s reflection on Kelty’s quote). Although this whole experience was unsettling – witnessing myself seeing the world in a different way, or perhaps just a different slice of the world (shoulders?) – that’s part of the job, right? Wait, which job – yoga instructor or ethnographer?

While the Albuquerque airport scene offers an acute example of how my yoga practice provides perspective – and the inclination to intervene – it also speaks to the flip side of being an instrument of knowing. Teaching vinyasa (a flow of physical postures that constitute asana, the third limb of yoga) means looking at student alignment and providing corrections. It also means that when a student comes to you with tight hamstrings, a bad back, or after recovering from wrist surgery, it’s your responsibility to provide that student with postures that will be safe and can address their needs. “Distance” may be long gone, but in front of a yoga class, it’s best to carry that “critical” stripe in your back pocket.

For me, “joining in and becoming part of the field” has been productive and rewarding. Admittedly, its not becoming part of the field that makes me nervous – it’s turning my yoga practice into ethnography that gives me pause. But the play between these pairs, ethnography and asana, writing and breathing, has been too interesting and rich not to engage.

I wonder how my situatedness will translate into writing, as it must. Kerim’s post on dissemination has me wondering if my position today will produce a sunflower or bougainvillea in the future.

Ali Kenner is managing editor and program director at Cultural Anthropology, and Adjunct Assistant Professor of Science and Technology Studies at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute. She also teaches Vinyasa and Kundalini yoga in Upstate New York.

“It’s another to know air quality in your body.” Ali, thank you for this sentence alone (if nothing else, although there is much more here to be grateful for). If we are using the self as an instrument of knowing, and sinking into the embodied, experiential as part of ethnography as a daily practice in both the doing of research and the writing of fieldnotes, then this sort of attentiveness to the self (as mind, body, etc.) makes real sense to me. What resonates for me is the idea of being more reflective than reflexive, of an attentiveness to what the self knows and how, rather than the now-passe (but persistent) stereotype of reflexive practice as navel-gazing narcissism; this is something different, a call for a deeper familiarity with our instruments and methods of research, and for a constant tending to and correcting our ethnographic alignments which I often describe to my students as the need and difficulty of “trying to stay aware of what you already know and don’t know” and which is shifting and growing but also receding each day in the field.

A(nother) beautiful post, Ali; one which resonates deeply–both as someone who’s practiced yogasanas since childhood, and as an anthropologist. The emphasis on the attentive-reflective (as opposed to the reflexive, as Carole notes) mode is indeed invaluable, but I’m moved also by your remark that joining the field gives you less pause than the prospect of turning that experience into ethnography. Indeed. While I can fully see the richness of engaging “writing and breathing” practices, I’m also tempted to ask, perhaps quite heretically: why must you write? This question is on my mind particularly because, in my examples, writing has actually not been possible–or has been a too-risky prospect that would involve treading too-fine balances. It’s that reality, given my position now mostly outside the academy, has me wondering about whether one needs to say anything at all, whether ethnography happens even sans the traditional forms of writing [a question on my mind in my moments-ago comment on Nate’s post], and what the products of our work as ethnographers could be, if freed from the usual career-building imperatives to disseminate–wholly or partially. Of course, we all always made ethical and strategic choices about what to write about, and how much. But now I’m wondering about the form ethnographic praxis might take in the absence of its most conventional final products–which ultimately protect our critical stripes, and foster escapes from our chosen fields. Or do they?

That’s a map showing concentrations of ozone, isn’t it? How does that illustrate your point about dry desert air vs. clogged up Massachusetts air?

And, of course, your intuitions can be wrong. It’s a lot easier for your “embodied” thoughts to be incorrect about the world than for scientific studies to be. A lot of people who practice qigong claim to feel “qi” flowing through their hands and head (as in, they seriously believe in a physical substance called “qi”), and another large group of people claim that mobile phones and communications masts cause cancer based on their feeling bad when using those things. But both groups are wrong; there’s no such thing as “qi”, and mobile phones physically cannot cause cancer – and they only cause headaches when people speak too loudly when using them.

Breathing and “embodied” studies are just poor, intuitive methods for finding things out when put up against powerful methods for finding things out – like scientific studies of air pollution.

I’m not sure what your point is, except that air quality reflects some sort of socio-political situation. Which, of course, it can. But the idea that you know this because of yoga or anything like that seems spurious at best.

Well, without breathing there are going to be precious few scientific studies of anything, but I digress. What she wrote was

The ICG expert understands famine; the person who hasn’t eaten for three days understands hunger. Each is privy to distinct but not unrelated knowledge.

As to the concept validity of qi, yes, there are a lot of New Ager loons who know a lot about nothing throwing the term around. That doesn’t change the fact that if you—by which I mean Al West—ever have serious long term back problems you will at some point start asking around about acupuncturists.

As to cell phones and cancer risk, the National Institutes of Health says that the jury is still out. Are you saying the NIH is unscientific, Al?

The ICG expert understands famine; the person who hasn’t eaten for three days understands hunger. Each is privy to distinct but not unrelated knowledge.

Deserved repeating.

The jury is always out in science – but as no studies show a link between cancer and mobile phone use (and no meta-analyses do), and as it is physically impossible for the microwave radiation employed in mobile phones to disrupt your DNA and cause cancer, it seems like we’re safe. There’s also the fact that something like two-thirds of earth’s population uses mobile phones regularly, and there hasn’t been a corresponding spike in cancer. It seems settled, but it could all turn out to be wrong. That would involve overturning the entire standard model of physics, but I suppose it could happen. It’s just that an individual experiencing headaches now and then isn’t sufficient evidence to do this.

As for qi, it doesn’t exist. I feel as comfortable saying that as saying that unicorns do not exist. It’s not just newagers who claim that it does, either. And the possible therapeutic effects of acupuncture aren’t evidence of qi – especially when studies have shown that the needles could be placed pretty much anywhere. Traditional acupuncture theory is seemingly unrelated to the possible pain-relieving effect.

In any case, Ali also wrote things like this:

Actually, it’s not. What is critical for asthmatics is carrying an inhaler and regularly checking forecasts of air pollution, pollen count, and other variables – not going out and experiencing them themselves. That can kill an asthmatic. The claim that experiential studies are equivalent in any way to scientific studies is just straight up wrong. Ali Kenner isn’t just saying, “sometimes I find it hard to breathe and have to pay attention to air quality, so I can understand a little of what it’s like to be asthmatic” – which might be a reasonable point.

No, she says:

That may indeed be so, but I see no way in which Ali’s method can reveal it. To use your metaphor, MTBradley, part of Ali’s claim seems to be that the hungry man can understand famine just like the ICG expert, just by examining his own hunger.

There are many gems in this piece, Ali. First, the whole theme of embodied knowing is very relevant to my ethnographic practice with dancers. Capturing in language the quality and “look” of bodies in motion is always a challenge, but your descriptions of breath and alignment are so vivid. Second, I am so excited to read Hahn’s ethnography. Third, I love the Ortner sentence–so simple, so apt. And finally, your description of the dailyness of your pranayama practice and how it can cause a continual unfolding of knowledge or insight is quite profound, and, I believe, has implications for how we understand the long-haul aspects of ethnographic work.

@Carole, thanks so much. I think calling for “a deeper familiarity with our instruments and methods of research” is spot on. And I think this is especially important when you sit down to write too, attending to how your own situatedness shapes the project — what you’ve seen and heard, and what you’re going to say about it. You get a nice grasp of the relevance of situatedness when you’re conducting collaborative research too — doing participant observation and qualitative interviews in pairs or groups. I’ve found that collaborative research is another practice that cultivates awareness, and asks you to tend to your instruments.

@Deepa, I absolutely love your question: why must you write? And also your “wondering about whether one needs to say anything at all, whether ethnography happens even sans the traditional forms of writing, and what the products of our work as ethnographers could be, if freed from the usual career-building imperatives to disseminate.” I ask myself that question A LOT in relation to my position at CA — if I want to ever get a tenure track position, I should probably try to publish on the work I do there, right? How will the work I’ve done at CA count when I apply for tenure track jobs in the future? So I am interested in thinking about the outcomes or “products” of ethnography.

When I step over to my ethnography of breathing, however, that question, “why must you write?” rings different. Part of the answer is that I love writing. But why write about breathing or ethnography or yoga and not something else? Why write for an academic audience, or for publications that have a relatively small audience? The plan, I think, is to take up this question in my final post.

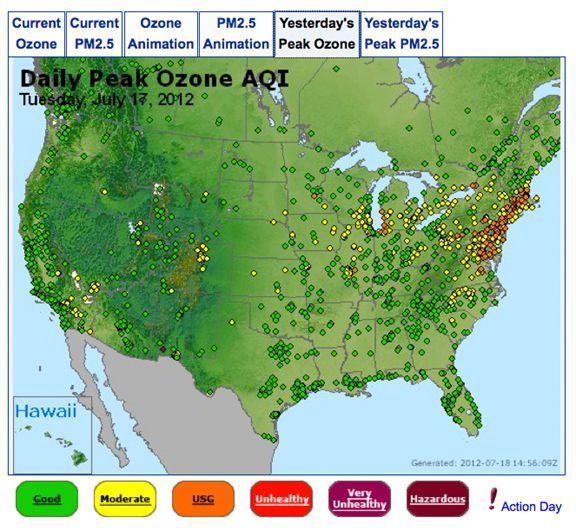

@Al West — thanks for your comments. The map that I used in my post comes from AirNow, which is an EPA run site that pulls data from municipalities across the country. The map shows peak ozone over a 24-hour period (July 17th) and the color coded tabs at the bottom indicate ranges that are harmful (orange means the air quality is unhealthy for sensitive groups, which includes children, pregnant women, the elderly, and people with breathing disorders). Anyone can go to the AirNow website and register to get daily air quality forecasts.

As for my point (or one of them anyway), I think MTBradley said it nicely:

“The ICG expert understands famine; the person who hasn’t eaten for three days understands hunger. Each is privy to distinct but not unrelated knowledge.”

So my emphasis here is on exploring different kinds of knowing, and the style or aesthetics of that knowing. The map and charts provided by the EPA are a very different epistemological register than a regular practice of breathing exercises.

The hungry man can absolutely understand famine. But I don’t think I would say “just like the ICG expert” and this man would need more than his own hunger to understand the complexities of famine. What I would say is that the man’s hunger offers a window into famine, a window that he could look into or crawl through. Something as large and complex as famine has many many windows that can be used, not just one. But all of this is potential, not a given. It’s what you do with these different registers, that’s what interests me as an ethnographer.

@Laurel George — thank you for your comments! I highly recommend Hahn’s book, which also provides a DVD that complements the text (dance instruction segments from the studio where she did her fieldwork).

Ali,

Thank you for your reply.

Or, die from. It seems to me that the best way to understand famine for any purpose at all is not to starve yourself, but to collect data on agriculture, social structure, climate, and international trade in affected regions over a number of years. It’s also arguable whether being hungry gives you any insight into famine at all. How does being hungry constitute knowledge? It’s like saying that being shot gives you an insight into ballistics. It’s only “knowledge” or “knowing” if you construe those words incredibly broadly, so as to include any possible sensation that you later have a memory of.

It’s the idea of “other ways/kinds of knowing” that I find untenable. People know things in only one way: by making observations and extracting some sort of general principle from them. When you find something out by breathing – like the fact that the ice cream you ate last night is still in your gut – you are finding it out in exactly the same way you find anything out: by using your broader nervous system to derive inferences from observations. Some methods of observation are superior to others, however, and I don’t think “embodied knowledge” is one of the superior kinds. To put it mildly.

That phrase seems a bit wrong, too. It’s an old humanist claim that you learn with your body – but you don’t learn or know using your body, per se. All of your knowledge is in your nervous system. Your muscles and bones cannot learn things. Learning or knowing anything is a cognitive process.

Comparing air quality and maybe even posture with all of the things you mentioned – race, class, etc – in the US might be an interesting sociological project. I don’t think breathing exercises give much more insight into this than sheer baseless speculation, however.

You’re playing with semantics now, Al. I ‘know’ how to touch type, something I ‘learned’ in high school. Basketball players ‘learn’ how to do a drop step and musicians ‘learn’ how to play scales. To be sure, ‘knowing’ how to play basketball and make music involve cognitive processes (by which I am assuming you mean something along the lines of ‘thinking’) but one does not play basketball or the piano with thought alone.

It’s not a semantic point. You can’t learn to do anything by thought alone, and that is not what is meant by “cognitive”. What’s important is that your ability to play basketball is not in your arms – it’s in your brain, and is determined by the ability of your brain to learn such things.

There is no difference between so-called “embodied knowledge” and any other kind; it’s all in the brain. You learn language, mathematics, basketball, origami, and social science by interacting with the world and affecting your (incredibly complex) nervous system. It’s very weird to say that someone is using “their body” as “an instrument of knowing”; either that’s totally incorrect (ie, the view that muscles have memory, etc) or it’s the way all “knowing” works (sense data and abstractions based on it, stored in the brain). Either way, it’s a superfluous phrase and idea.

And this whole idea of investigating social scientific issues using “the body” is predicated on the notion that it is in principle different from other kinds of investigation – when actually it’s the same in principle to, say, EPA studies, but with a narrower scope and more susceptibility to bias and inaccuracy. Instead of lauding it as of a “different epistemological register”, we should ignore it as a relatively useless, intuitive method of finding things out.

I am left wondering what a game of basketball featuring ten wo/men possessing ten apt–for–basketball brains would look like if they all had their hands tied behind their backs.

A better example would be a team of people who used to play basketball, but whose arms had been amputated and replaced with high-tech prosthesis that connected to their nervous systems. The ability to play the game isn’t in the muscles or the bones, or “the body”, just as the thing that makes a car move isn’t in the wheels. It’s in the nervous system. That’s the point, facetious examples aside.

If your interest lies in engines, that’s fine. If your argument is that the most vital part of a car is the engine, that’s supportable. If your contention is that a car is going to self-propel without a transmission system or wheels, that’s ridiculous. If your logic reduces the whole of an automobile to its engine, your thinking is faulty.

That sort of Kurzweilian semi-empirical example may hold water with some interlocutors. I am not one of them.

MTBradley,

The main point is that using “the body” as an “instrument of knowing” is either wrong, or it’s what we do all the time, rendering those phrases and ideas useless. Going by intuitive reasoning on the basis of immediate sensory information is not the best way to find anything out. It is not different in kind to scientific studies, nor is it “another way of knowing”. It’s just a poor method of investigating anything except the contents of your own body, and even then it relies on considerable other knowledge (such as remembering that you ate ice cream last night), all of which is stored in your nervous system.

Yes, you need arms to play basketball and you need wheels for a car to move, but the knowledge of how to play basketball is stored like all other knowledge, in your brain/nervous system. That’s the point I’m trying to make: all the knowledge you know is known through your nervous system, and primarily your brain, and that applies equally to basketball-playing knowledge, yoga asana knowledge, and mathematical physics knowledge.

That’s not reducing the car to its engine. The engine propels the car, and a human brain knows things. The wheels don’t propel the car, and arm muscles don’t know how to play basketball. So the idea of “using the body as an instrument of knowing” either means business as usual – using your senses to find out about some aspect of the world from which you can draw conclusions – or it’s nonsense, predicated on an incorrect view of how humans work.

Well, that’s okay. But could you say why? Would you be happier with a phantom limb example? That would be just as valid. And of course, there are plenty of existing examples of robotic/myoelectric prostheses manipulated by neurons in the same way a person uses their biological limbs. They’re not all that new, and they’ve got nothing to do with Kurzweil.

The assumption that knowledge is “in” the brain and nervous system, itself only a transformation of knowledge is “in” mind and not embodied, may not be a useful guide to understanding the sort of thing that Tomie Hahn writes about in Sensational Knowledge, the ethnography to which Deepa points us. The following sample of the writing in question is copied from the page to which the link that Deepa provides takes us.

I remember my first dance lesson with Iemoto (headmaster) Tachibana Yoshie in Tokyo. She took my elbow and led me across the studio, pointing at the impeccably clean wood floor. Nothing seemed unusual. “See these marks . . .,” she said, kneeling down on the floor and still pointing here and there. As I bent down to sit by her side, minute water marks and nicks on the floor’s surface came into focus. “Those stains are from all of our sweat and tears here together,” she continued, sweeping her arm across the room toward the half-dozen onlooking students. “All these marks are from our hard work together everyday––dancing.” I looked up from the floor to the students and down to the floor again. My eyes, now wide open, saw how speckled the floor was. In conversations “Hatchobori” often becomes a metaphor for our dance lives, relationships, obligations, and the Tachibana dance tradition.

The above story illustrates how this “house” (“ie”) embodies our dance, and how each of us contributes to the physical form of the house. The surface nicks and stains are insignificant in themselves, but they are a tangible result of physical exertion during the process of learning. They are manifestations of the hours we practice there together, generations of marks layered upon each other. Dancing bodies created these marks which are symbolic contributions to the larger representation of the school body and an instantiation of our strong bonds.

Sensational Knowledge: Embodying Culture through Japanese Dance is an ethnography offering a peek into some of the everyday life at the Tachibana school of nihon buyo in order to convey the sensitivities of the culturally constructed process of teaching. Since childhood, nihon buyo has been a part of my life. This led me to question how we learn cultural sensitivities of the body in such a way that they seem second nature, reflecting our sense of self, as well as how we come to understand the world around us. The site of my field work was primarily at Hatchobori, the main Tachibana dance studio in Tokyo where the Tachibana headmasters reside and teach. The themes in my writing rose from my experiences similar to the one related above. Each experience encapsulates the essence of our dance household life at Hatchobori and in the process, reveals the tradition of dance transmission through generations of dancers. The physicality of transmission is stimulating. The art, simply, is learned and passed down through moving bodies. However, this reality unfolds into a deeply complex web of interconnected impressions enacting cultural meanings.

I write as someone who has spent a could deal of time over the last three years as a member of a men’s chorus, each of whose rehearsals begins with physical exercise to loosen up our bodies, followed by voice training, which depends in large part on the director’s attempts to get us to stand properly, chest expanded, stomach and throat relaxed breathing in through our noses, feeling the upward movement as our stomachs contract, and learning to guide the air on a path that feels like it is moving up the back of our spines and following a curved path along the tops of our heads. Anatomically this is nonsense, but it makes a huge difference in the quality of the sounds we produce. And that is precisely the point—no amount of cognition per se achieves the desired result. Only practice and feeling the difference will. The critic may say, “It’s all in your brains and nervous systems,” but if we say, “Show me,” there is nothing to see. The “Show me” that produces a useful outcome is the director demonstrating the correct posture and encouraging us to act and feel in ways that do, in demonstrable fact, affect the sounds we produce.

They are the same thing. Feeling, thinking, practicing – it’s all done using the nervous system, not some extra-nervous sensory apparatus. The view that “feeling” is different to “thinking”/cognition is very odd; they’re basically the same thing in this instance, or at least there is no sharp, meaningful division between them. You have also clearly thought about the singing procedure, as have others; you have observed that adopting a certain posture produces better sounds, and have ensured to continue adopting this posture when singing. It’s not something you know simply by adopting the posture and “feeling” simplistically, without any feedback from other data about the world.

You and others have concluded on the basis of the evidence available to you that singing in a certain way produces a better sound, which is your aim. Clearly cognition, even in the stripped back sense in which you mean it, is present.

In any case, the important thing is the claim that “embodied knowledge” is of a different “epistemological register” to a scientific study, that it is “another way of knowing”. And as you in fact have demonstrated, it isn’t. You are using your senses to acquire data, which is in principle no different to science. It’s just a rubbish version of science, the “trust your gut” position. That would be a fine position if it weren’t demonstrably worse at finding things out than a scientific procedure.

And you saying “show me” is a bit odd. No, knowing that your singing ability is encoded in your nervous system probably won’t be of any use to you in improving your singing, just as a physicist knowing that her knowledge of physics is encoded in her nervous system won’t help her conduct experiments. But that’s not my point; my point is that “using the body” is either the same as using your mind/brain/nervous system, or it’s nonsense, and in either case, the notion is purposeless.

“Embodied knowledge” is not novel or interesting. It’s not “another way of knowing”. It’s just a bad use of the only way of knowing that there is – sense data and inferences made on the basis of it.

Al, you haven’t asked yourself why a lot of very smart people take this notion seriously. All you can do is insist that science is the only true way to know. You could be right. But your argument is no better grounded than that of a Bible-thumping preacher who claims he knows the big capital-T Truth.

Most of the people I know who are interested in embodied knowledge aren’t there because they’ve gone New Age and believe in mystical powers. They are people who observe that abstracted knowledge based largely if not exclusively on visual input and sometimes formulated in mathematical terms is only a subset of what there is to be known. They can be, for example, the designers of the new exhibits at the National Museum of Ethnology in Osaka, Japan, who are now allowing people to pick up and handle some of the materials on exhibit, to give them a feel for the material that no amount of staring at it provides. They can be psychologists who observe that brains and nervous systems detached from other organs don’t learn anything—they die—and wonder what the rest of the body has to do with learning. They can be people who study or teach the arts for whom the statement “The learning is in the brain and nervous system” is pointless when it comes to learning what they want to learn and teach. Ditto for athletes and coaches who train them. The man with the Bible says, “See the glory of God.” The man with a science fetish says, “Behold, it is in the brain.” Who you gonna believe? Let’s give the guy with a science fetish the edge; he can point to pretty MRI scans that show brain activity as people learn stuff. But, hey, the guy who teaches shop or art or football doesn’t need an MRI to see and feel the difference. Neither do his students. The claim “It’s all in the brain and the nervous system” is immaterial to what he’s trying to accomplish. There is more in Heaven and Earth than imagined by your brain.

I like the javelin, and I used to be quite good at it. Quite a visceral sensation, heaving a metal spear down a field and watching it stab into the earth. It’s a complex procedure; you’ve got to keep the javelin at the right angle through the throw, ensuring that it is going straight from the first movement of your arms to the moment that it leaves your fingers. There are so many little adjustments that separate the great javelin throwers from the PE teachers of the world – from the position and angle of the feet to the efficiency of the turn of the hips in adding power. There’s a “feel” to a good throw, and a “feel” to the javelin in the right position in my hand.

But it’s still a cognitive procedure – just a very complicated one. I’m using my senses to gather data, correcting my posture and the tension in my hips on the basis of largely unconscious comparisons between previous throws and current sensations – amongst much else. There’s a “feel” to a throw that I can’t communicate accurately to you, but that’s presumably because motor control is a more primitive and pre-linguistic area of the brain, not because it’s the product of a non-cognitive process.

Take a look at these flying robots (WARNING: TED link) and let me know if you think they’re thinking, feeling, or doing something completely different.

The way I know how to throw a javelin is essentially the way in which I know anything else, and knowing how to throw a javelin doesn’t give me any privileged information about the social aspect of javelin throwing, or about any supposed connection between the strength of the deltoid muscles and class. If I know anything about those things, I know it from other sources, in the same way I know anything else like that.

Except that that’s complete bullsh*t. I’m working from first principles and trying to understand what “embodied cognition” could fundamentally mean. And my argument isn’t that intuition is completely useless. It’s that intuition is just a place to begin, and is often incorrect – much more likely to be so than scientific studies. Finding anything out takes work, not intuitive reasoning on the basis of immediate sense data.

And I assume that lots of smart people believe in “embodied knowledge” because smart people are just like anyone else, and they are capable of believing in stupid and ridiculous things. Lots of smart people find Gilles Deleuze reasonable. Others thought Stalin was just fine. Smart people can believe in rubbish, especially when they have no reason not to, and unquestioning humanists seem to have no problem with believing in unnaturalistic things.

Al, you said it, “I assume.” One of your most annoying assumptions is that the people you are conversing with are the idiots to take them to be. In my experience, a great many of them may, indeed, be idiots. It is always polite, however, to withhold judgment until you have asked yourself and them if there might be something in what they are saying that you haven’t grasped yet. You present yourself as a fundamentalist saying “My way is the only way.”

The fact of the matter is that you haven’t cited any recent research to support your assumption that the brain and nervous system are the only places that learning goes on. You have only stated it as if it were self-evident and anyone who disagrees must be a fool. It is not surprising that our younger members appear to have taken what is likely the wiser course, to simply ignore you.

Personally, I think you have a lot of good stuff to say. I welcome your support for solid science when too often people are being silly. But in this case, I genuinely believe that you are damaging our cause, because by adopting the tone of a strident preacher scolding the sinners in his congregation you are turning people off. You might want to consider that.

It should be self-evident that the nervous system is the only thing that can feel or store information; it’s up to you to provide evidence that the inverse is true. The null hypothesis is that the nervous system and the brain feel and know, and if you have some evidence that muscle cells can feel in absence of neurons or axons, then I advise you to make it public. There’s 8,000,000 Swedish kronor in it for you.

I no more need to cite studies on this than on the fact that your heart pumps blood. An anatomy textbook would do just fine.

I’m not saying that. I’m saying that the idea of embodied knowledge seems like nonsense – and there doesn’t seem to be a single reasonable defense of it. It’s possible that I’m wrong; I certainly haven’t published anything on embodied knowledge or neurons. But no one has defended it. That may be because everyone thinks I’m a crazy fundamentalist who won’t accept any evidence as good evidence, but even so, there has been no reasonable defense. You attacked a strawman (several of them, including the classic humanist strawman of scientism), and no one else has bothered to defend the idea properly despite publishing articles on it. We’re talking about people who have published on the idea, and they can’t even defend it. Or, at least, they haven’t.

Even if a raving lunatic turned up in a thread and started spouting nonsense, I wouldn’t ignore them; I’d point out why they were wrong. Physics bloggers confronted with people claiming to have invented a perpetual motion machine don’t just let them rave on – they challenge their claims and say precisely why we shouldn’t expect there to be any perpetual motion machines in existence. But no one here has provided any good reason why we should accept the idea of embodied knowledge. Naturally, I remain unconvinced, and since nobody can defend the idea to me, I am forced to wonder how they defended the idea to themselves in the first place.

I don’t assume that anyone here is an idiot, just misguided.

I’m not saying anything outlandish here, either. Even if muscles could learn, so what? Would that give sports and stretching the ability to discover facts about social structure? And it would still mean that all learning is of the same kind – using senses, apparently including the muscles somehow, to uncover data about the world, putting all such claims on the same epistemological plane as science.

There is more to the investigation of humanity than discerning facts about social structure, that’s what. (For one!) The Great So What, which always says just as much about the individual posing it as it does about the individual to whom it is posed…

Al, I already provided the evidence. Extract the brain and nervous system from the other organs and they learn nothing. They are dead. The prima face case is that both brain and muscle are necessary for learning (also brain and stomach, liver, heart, lungs, etc.). No learning occurs unless they are all present and functioning. There is evidence that activity associated with certai kinds of learning is localized in certain parts of the brain. There is also evidence that single-celled animals with no brains at all and flatworms that have no brain to speak of learn. They don’t learn languages or calculus, but the critters that do, i.e., us, have a lot of other stuff going on besides specialized brain and nervous tissue, which, as noted above, learn nothing without the other parts present. Experiments that demonstrate that removing certain parts of the brain affect various forms of learning are no more definitive than the observation that shorting a light switch causes the lights in one room to go out. Neither demonstrates that the learning or electricity in question is found only in that particular spot. In sum, what you take to be evident is not evident at all on closer examination. Ball is in your court.

MTBradley,

Undoubtedly. But what exactly do you think “embodied knowledge” could investigate? What is it that sensory muscles would be able to research (the “so what?” was related to the point about muscles learning, not the entirety of the conversation, by the way)? How would it be any different to studying those things using your ordinary senses? How would it be any different from sheer intuition? And would it be removed from the sphere of what science can investigate? And, if so, why?

The reason I asked about social structure was because Ali Kenner in her post discussed a connection between breathing and various social structural aspects – class, etc. I don’t believe it is the only thing we can investigate.

The wheels in a car do not provide propulsion. They allow the car to move, but they don’t move it. The engine propels it. The wheels are necessary for it to function, but they do not themselves propel the car. Likewise, the heart doesn’t learn things. It is necessary for the brain to work (although an artificial heart does just as well), but it is the brain that knows things, not the heart. The heart knows nothing.

And yes, experiments showing that removing parts of the brain removes mental faculties associated with them is evidence that the brain learns and nothing else. But even more compelling are studies of phantom limb patients. When a limb is severed, many patients can still feel the limb present. They feel itches and pains in their phantom limbs, even after many years, because while the limb isn’t present, the relevant part of the brain is. The limb isn’t strictly necessary for a human to feel sensations associated with it.

Furthermore, absence of evidence is evidence of absence, and there is no evidence, besides your very strange conceptual argument, that hearts, livers, and muscles are capable of learning anything. You say that without the heart, we wouldn’t be able to learn anything. So we’d be dead – well, all that means is that the brain needs blood, not that the heart learns.

What you need is for blood to keep getting to the brain, not for the heart to be functioning. While they usually amount to the same thing, it’s not the case that the whole body is necessary for learning. Likewise with the stomach; the brain needs nutrients, and it is the nutrients, not the stomach, that are necessary.

I find your faith in this argument mystifying. It’s also a non-sequitur. If you’re trying to show that embodied knowledge of the kind espoused in the main post above is possible, then the fact that the heart is necessary for learning is only relevant if the heart itself learns, and learns in a way different to ordinary learning through sense data in the nervous system. You haven’t shown that.

Preacher man, you just keep repeating these things as if they were self evident when I have pointed to clear evidence that they are not. That’s blowing smoke, neither fact nor logic. Enough of this.

Al, you’re in a muddle.

Valuing embodment as a method in learning (the body as an instrument of knowledge) does not entail any claims about the locus of knowledge as it is ‘stored’ in the body/nervous system nor does it necessitate a specific stake in mind/body dualism. Thats a non sequitor. Maybe your knowledge of playing basketball is ‘stored’ in your brain, as the computer metaphor would have it. But that’s not the point, which is rather that you can’t learn to play basketball well by simply consuming representations of basketball (which is what science will produce). You need to play it. You ask what ‘could embodied knowledge’ investigate? Well, playing basketball for one. Or dancing. Or driving. Or identifying a good place to build a hut (see Bloch 1991).

“How would it be any different to studying those things using your ordinary senses?”

To study anything, particle physics or medieval Islamic poetry, you have to use your ordinary senses.

“How would it be any different from sheer intuition?”

Depends on what you mean by ‘sheer intuition’. If by intuition, you mean skill developed over a long period, high-speed pattern recognizing cognition, then perhaps it is quite similar. If you mean intuition as random guesses and whims of fancy, then quite different, obviously.

“And would it be removed from the sphere of what science can investigate? And, if so, why?”

Distinct, yes. Because there is a difference between external, linguistic-based representations of things, like the second-order knowledge produced by science, and the first-order knowledge is ‘stored’ in the body/brain. You can have all sorts of scientific studies of basketball: physiological, biological, physical, statistical. Not one of those studies is the same as the skill to play basketball. Again, see the Bloch article.

Finally, somewhere you said that scientific knowledge is more valuable. Returning to basketball, well, let’s just note the salaries…

Bloch, Maurice (1991) LANGUAGE, ANTHROPOLOGY. AND COGNITIVE SCIENCE

If you can provide more justification for your beliefs than your conceptual argument – which doesn’t justify what you appear to believe that it does – then I’ll accept that you are right. But your argument was not very good, and I explained why. Even if it had been correct, it still wouldn’t have justified belief in the kind of “embodied knowledge” we’re talking about. You may believe these are mere assertions, but they aren’t, and I justified them above.

There’s plenty to read if you’d like something more than just my arguments. Try Ramachandran‘s Phantoms in the Brain or something like that. It’s not like the neuroscience literature, even the pop literature, isn’t voluminous.

Oh, and flatworms may not have brains, but they do have nervous systems. They don’t have respiratory systems, IIRC, but they do have a rudimentary nervous system. A brain is, after all, just a centralisation of the nervous system, not something different to it. The fact that flatworms can learn things isn’t evidence in favour of your position at all.

There’s no need to get so frustrated, nor to resort to slurs (“preacher man”).

Maniaku,

So, what happens when you write something down about “embodied knowledge”? Take Ali’s post: isn’t that precisely the same as a scientific study in this sense? It’s a second order linguistic representation of inferences made on the basis of sense data, which is also what a scientific study is.

Science relies on sense data first and foremost. The senses are extended using a variety of tools, but it’s still sense data, just like you use when learning to play basketball. What’s different between writing up a report based on sense data from a scientific experiment, and writing up an article based on sense data from a breathing exercise? It’s still a second order representation based ultimately on sense data. The distinction between them doesn’t seem to exist. They both use the senses to understand the world and communicate that understanding to others. The difference isn’t in this principle, but in the scope and verifiability of the results of the inquiry.

“Using the body as an instrument of knowing” seems to apply just as well to scientific studies as to learning sports, if we take your view. You’ve only distinguished between embodied learning and scientific understanding on the basis that science is second order and embodied knowledge isn’t, and that distinction doesn’t hold up when you remember that so-called embodied knowledge is also written about and scientific inquiries are based on sense data of the same kind as employed when learning to play a sport.

I also think sports like basketball are much more cerebral than the picture presented here. You don’t just learn basketball by playing. You learn it by discussing plays, going over and over in your head how you would react to a pass, watching games on TV, learning the rules from friends or a book. It requires thought, not just instinct or intuitive actions. It relies on second order representations as well as playing it first hand.

Ali,

Fantastic contribution. Reminds of my experience training in pugilism and the range of imperatives spouted by my trainer such as don’t hold your breath; breathe in deep through your nose exhale through your moth; inhale when your contract your punch, exhale when throwing. Had it not been for the trainer’s watchful eye, I would have been unaware of both my own breathing rhythm and how I should breathe. Such a feat requires consistent practice. Again, good post.

Pretty interesting discussion going on here.

Al wrote:

“But it’s still a cognitive procedure – just a very complicated one. I’m using my senses to gather data, correcting my posture and the tension in my hips on the basis of largely unconscious comparisons between previous throws and current sensations…”

I agree with you about the point that we are still talking about cognitive procedures, basically. But I think when people are talking about “embodied experience” and such, they are trying to get at those “largely unconscious” kinds of actions that you mention. There is something more to learning (basketball, fishing, whatever) than just thinking about a particular activity. But as you say, it’s a complicated process.

“There’s a “feel” to a throw that I can’t communicate accurately to you, but that’s presumably because motor control is a more primitive and pre-linguistic area of the brain, not because it’s the product of a non-cognitive process.”

Do you think motor control is more “primitive” in the sense that it’s less complex, or more primitive in the sense that it simply came before language? I think this particular issue you bring up is interesting. I think this ‘feeling that cannot be communicated’ is party what some folks are trying to get at here. Just a thought. But I think this issue of learning or knowledge that can and cannot be explained or verbalized is really interesting.

Later Al wrote:

“I also think sports like basketball are much more cerebral than the picture presented here. You don’t just learn basketball by playing. You learn it by discussing plays, going over and over in your head how you would react to a pass, watching games on TV, learning the rules from friends or a book. It requires thought, not just instinct or intuitive actions. It relies on second order representations as well as playing it first hand.”

Sure, you learn basketball by thought–but all of that is only going to get you so far. There are people who know all of the theories and rules and regulations of basketball to the nth degree, but when they step on the court they can’t play (they end up as a species called “sportscasters” I think). I agree that a certain amount of “second order representations” are part of the picture, but I think the real learning happens by doing, or at least thinking in a different way while doing at the same time. Maybe what all of you are really arguing about is the difference between calling something “more cerebral” versus calling it “embodied experience” and what that means in cognitive terms.

I remember I read this book about Pistol Pete Maravich. He was a great shooter. He said that every time he took a shot, he would imagine a tiny version of himself shooting and making a basket (something like that). Did he *think* his way to becoming a great shooter? Well, he also said that he spent thousands of hours shooting and shooting and shooting from every part of the court. Hmmm.

I grew up playing baseball, and wanted to be a great hitter like Rod Carew. I played from 5 years old until I graduated high school. I was always good, and had a certain talent for it. I also played a TON of baseball. But things changed when it all got more competitive in high school. The pitchers were better, and my hitting ability went down the drain. I am someone who learns by reading, watching, and thinking…so I watched a lot of Rod Carew hitting videos, talked and talked to coaches, read books, all that, trying to get better and keep up. Now, a great hitting coach and some hitting instruction video can help to an extent, but there’s something more to it. I’m telling you–I would sit there and watch Carew’s hitting videos for hours. The great hitters in baseball put in a lot of time–in batting cages and in actual game situations. Practice matters. Then there’s the question of “skill” or “talent” or whatever. Needless to say, I never became a great hitter, and I’d argue it’s mostly because I didn’t really put in the serious time in the cages that some of the other guys did (the guy on my HS team who spent the most time practicing ended up doing pretty well in MLB). The skill or talent factor is another complex part of the puzzle, along with motivation or drive. If hitting was a matter of just thinking about hitting in an abstract sense, however, I would have been a great hitter. I put in plenty of time trying to hash out what it all meant, but when some insane curve ball came at my head–no matter what I technically knew about the situation–I would often instantly react the wrong way. In order to get really, really good, I probably needed a few thousand more hours of seeing curve balls break until I learned–one way or another–how to deal with them without pulling my lead shoulder. As it turned out, my baseball career was over by high school. In fact, I was a better hitter when I was younger and relied on practice and skill than when I tried to get technical and start theorizing about hitting.

For my last example I’ll use surfing. Technically, I “know” how to surf since I started when I was 11 years old. I learned by being in the water for hours and hours and hours when I was a kid. Day in and day out. Ya, I also learned by watching friends and checking out surf videos–but the real learning came through practice. I could think about doing certain things before I could actually physically do them. Surfing is something where you have to have a certain feel for tons of things at once, and sometimes things are working well and other times you’re off. Also, if you are out of practice–even though you know what you’re supposed to do in a situation–your ability to do certain things can get a lot worse. To me this is really interesting–if you “know” how to do something in a cognitive or intellectual sense, then how can your ability actually decline? Is it because there’s another complex layer to this kind of activity or knowledge? With surfing, the more you are in the water, the more “in tune” things are–for the most part. It’s hard to explain. But when I have not been in the water for a long time, reading a book about surfing isn’t going to help one bit. That’s just not how it works. I have to get back in the water and start getting it all back in order again. When people ask me how they can learn how to surf, I can tell them a,b,c and d about what they should do. But there’s so much to learn, and so many things going on, that the only real way to learn is to go out there and start getting the hang of how it all works. Overall, Al, I agree with you that this is still a very cerebral process, and a complex one at that. I just think that there’s a certain aspect to this kind of activity or learning that some of the other folks are trying to get at, and I think there’s something to what they are trying to highlight.

I tried to make clear earlier on that I thought that there are two possibilities with the idea of “embodied knowledge”. Either it’s the same as other kinds of knowledge – learnt through the senses and stored in the nervous system, and fundamentally amenable and open to the scientific process – or it’s another kind of thing, based on the idea that people learn using their bodies rather than simply their nervous systems, rendering it less naturalistic and not amenable to the scientific process.

If it refers to that sort of “feel” you get for particular activities, then it’s still a cognitive procedure, learnt through the senses. “Cognitive” doesn’t mean “pure thought”. It’s not any different to other kinds of learning. But I think the phrase refers to something else: the idea that the body knows things rather than just the nervous system. That doesn’t appear to be correct, and it seems more like a way to covertly introduce speculation and a heavy dose of intuition into the academy.

Also, much of cognitive science is based on unconscious calculations, only some of which could be described as that sort of “embodied” feeling. Linguistics, for instance, is predicated on the idea that people unconsciously learn rules for using sounds and gestures in communication. So here, there doesn’t seem to be a distinct line between unconscious “feeling” and unconscious “thinking”, especially as language learning – almost the archetypal cognitive procedure – requires an unconscious feeling for correct usage, one that isn’t “embodied”.

“Embodied” is also a misleading term; the knowledge is stored in your brain, not in the limbs, just as your language ability is stored in your brain rather than your vocal cords. It seems like a useless term to me, especially as – on the basis of this thread in particular – it seems like a very ambiguous one. Perhaps that’s part of its appeal.

The latter. It’s incredibly complex, and any AI researcher who has worked on it will tell you that programming robots to achieve a similar level of motor control to humans is almost impossible at the moment. Those robots in the TED video from the Penn lab are fantastic examples of what can be done, though.

You’re right: practice matters. It’s easily the most important thing in sport. But practicing is how humans learn these things – it’s how they take in the incredibly complex combination of principles required to move your body around according to rules both physical and social. That’s a very difficult thing to do, if you’re not programmed to do it.

That’s also one of the things AI tells us. Doing mathematics or playing noughts and crosses – these are really easy activities to programme. They require only that the programme focus on one task, an entirely logical task that requires little or no interaction with the world. Hard for humans, easy to programme in robots. Sports, on the other hand, are difficult for robots. They require keeping count of a huge number of things, including making very fine adjustments in movement, which is tricky on its own. Easy for humans, hard for robots.

When we call this incredible, astounding complexity of thought in action “embodied knowledge”, we do it a real injustice. It’s easily some of the most intricate stuff that people do, and the only reason it seems so easy to, well, walk around is because the bits of your nervous system that take care of it are incredibly ancient and operate unconsciously. It’s still a cognitive procedure – still a learning process reliant on the ability of your brain to coordinate a lot of information. You learn it as you learn anything else, but in this case you’re basically programmed to learn it. You aren’t programmed to tackle higher mathematics. That may be what gives rise to this “feel” to perfecting movement in physical activity.

The ability to perform complex physical movements and do sport is probably the most powerfully intelligent part of humans. But it doesn’t mean that it’s a fundamentally different kind of knowledge to mathematics (at least, in the way it’s learnt and stored), and it doesn’t seem to give rise to any ability to understand anything else – social scientific issues, for instance. What I’m trying to get at is not a relegation to irrelevance of intuitive actions or anything like that. I’m just saying that “using your body as an instrument of knowing” is either commonplace and relatively useless for anthropologists studying sociological questions and problems in human diversity (but worthwhile for psychologists and artificial intelligence researchers), or it’s non-existent and based on an incorrect understanding of how people work, and in either case the phrase itself is pointless and misleading.

Al,

It is a fair point that written accounts of embodied knowledge (or non-linguistic, expert knowledge, if you like) are not the same thing as that knowledge itself. And ‘scientific’ accounts are also written. It follows that both are written…

But then, “What’s different between writing up a report based on sense data from a scientific experiment, and writing up an article based on sense data from a breathing exercise?”

Well, I’m kind of at a loss on how to answer this question. One is based on sense data from a scientific experiment. One is based on embodied knowledge from a breathing exercise. This I think qualifies as a ‘distinction’, despite your claim to the contrary. Since that is obvious, you then concede that the “only difference is their ‘scope’ and their ‘verifiability'” If that is your position, then you are smuggling a lot into the word ‘scope’ including ‘contents’, ‘significance’, ‘meaning’, and ‘methodological basis’.

About verifiability, from the Bloch:

As far as the ‘cerebral’ aspects of basketball, that can be granted. But it is you who is insisting that embodied knowledge has no place. It is not the original poster insisting that scientific, linguistic, or representational knowledge has no place. In fact, its actually an example of those different kinds of knowledge being combined.

It’s rather curious your focus on robots. You do know that it is in robotics that the notion of embodiment has been adopted with the most enthusiasm? Perhaps you are unfamiliar with Rodney Brooks and “Intelligence without Representation?” Or Minoru Asada (on the topic of sports, coincidentally one of the main proponents behind RoboCup, the robot soccer event) and “Cognitive Development Robotics”? The standard AI narrative is that the failure of AI is due to the disembodied concept of cognition that early researchers worked with. You know… the position that is, essentially, the one you have taken in these comments. Embodiment as a theory of cognitive functioning has its critiques: an easy to understand and rather well-thought out one is made by Jerry Fodor in an LRB review (with an equally interesting rebuttal by Andy Clark, which speaks to your “amputee thought experiment,” at the end). It is available here: http://www.lrb.co.uk/v31/n03/jerry-fodor/where-is-my-mind). Your critique is not one of the better or sophisticated ones, however.

Al, I didn’t make a “conceptual argument.” I pointed to indubitable facts. Brains and nervous systems separated from the rest of the organism learn nothing at all. How could they? They are dead. You are the one who is insisting that learning is localized in the brain and nervous system but offering no concrete evidence for the proposition that would separate it from any other bit of folk pseudo-science that sounds right because it fits assumptions that are culturally widespread but, as you yourself would point out in other cases, of no particular merit because they are popular.

We know that it is a long-established prejudice in, what for lack of a better word, I will call the Western tradition that reason is something categorically different from and hierarchically superior to mere animal and vegetative functions—the scheme can be traced directly to Aristotle and endures in medical descriptions of patients in irrecoverable comas as being in a vegetative state. We know that the separation of mind/reason from matter/body was sharpened by the Cartesian turn in philosophy, which set the stage for all sorts of fuss about the mind-body problem (how does one affect the other) and all sorts of epistemological pondering about how information about the material world gets into the mind. I would suggest that the “obviousness” of the proposition that learning is localized in the brain and nervous system but NOT in other organs is rooted in this tradition—whose popularity, I note again, is no more guarantee of its validity than the beliefs of several hundred million Chinese guarantee the validity of the Yin Yang and Five Elements cosmology that underlies Chinese popular religion or the beliefs of tens of millions of Catholics make the Pope infallible.

On the other side of the count, a look at the history of renewed interest in embodiment suggests that it arises from a reaction against the abstractions of sociological theory and, in particular, rational-choice theory derived from economics, which restrict what is important to life and learning to what goes on in the black boxes inside our skulls and assume computational processes that any computer scientist can tell you lead to combinatorial blowup and frozen systems. There is now a good deal of serious work on brain and nervous system interactions with other organ systems (For pointers I’d recommend a look at Greg Downey and Daniel Lende’s Neuroanthropology blog). As far as I can see none of it, zip, zero, none of it supports the simplistic proposition that learning occurs only in the brain and nervous system.

If you no of some evidence to the contrary, please do share it. Your assumption that what is obvious to you is obvious to the rest of the world is demonstrably mistaken.

Hi all, apologies for the delay and not partaking more in this discussion. I’ve really appreciated what I’ve just read this morning and think this discussion thread demonstrates well the difficulties of writing about what we know and how we know it. Important to this thread was how to assess and evaluate knowledge claims, which is critical in the contemporary moment, in so many ways. I don’t have much to add in this regard, except to say that I think there are great examples of how science has been improved by modes of knowledge that don’t fit the dominant paradigm. Evelyn Fox Keller’s book on Barbara McClintock is one example (A Feeling for the Organism).

This thread also shows the great range of topics and relationships that embodied knowledge touches upon, and I think the path discussion takes here is fascinating. Lots of great material came out of it. Many thanks to all who suggested literature, and maniaku in particular. There is also a substantial and rich literature on embodied knowledge in anthropology, a literature that does a great job of introducing and diving into many of the issues raised here.

Part of my interest is in what bodies can tell us about the environment. How we measure the intimate and in-depth knowledge asthmatics have with respiration and their environments is a live area of research. One project I’m watching closely is Asthmapolis (http://asthmapolis.com/), a public health project that uses an inhaler rigged with GPS and a mobile application to gather data about asthma as a chronic condition – when and where the inhaler is used, as well as the trigger that provoked symptoms. It’s a great example of a project that translates embodied knowledge into larger information systems.

@John McCreery, I really appreciated and enjoyed your description of singing and the detailed attention to posture and breath.

@Al West, I think you’d really enjoy the work of Elizabeth A. Wilson. Her most recent book, Affect and Artificial Intelligence is excellent.

Anyway, we shut this thread down since we didn’t feel it was adhering to the comment policy. I’m happy to carry on discussion with anyone via email.

Ali, would love to continue via email but when I check your website I find no email address. If you would like to send it privately, I can be reached at john.mccreery@gmail.com.