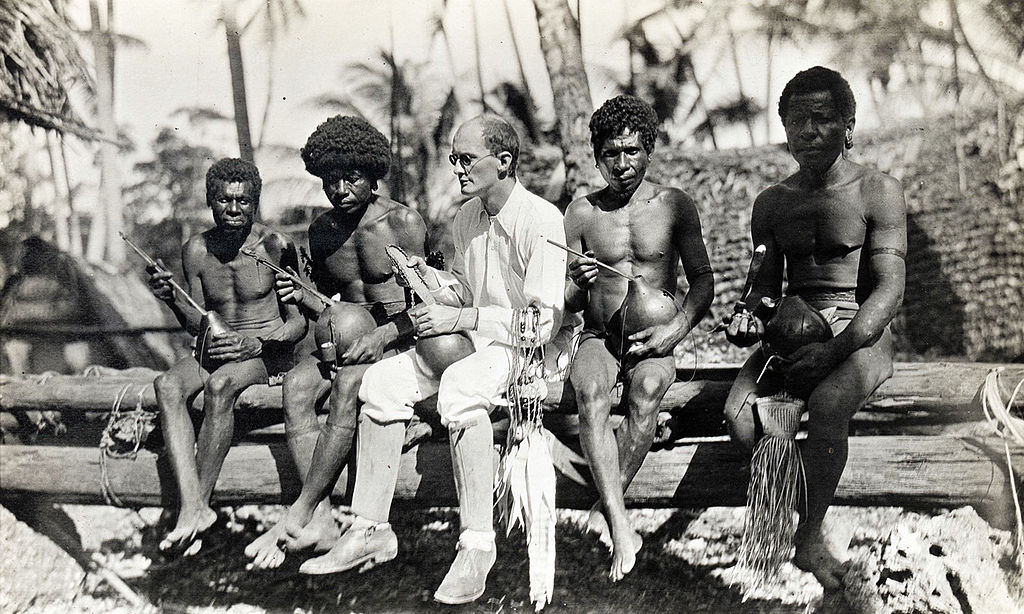

If there’s one picture that epitomizes White Guys Doing Research, it’s this one:

The canonical author of the canonical book, naked black people, white guy in white clothes being White — for a lot of people, it’s totally crazy-making. But in many ways, Malinowski was far more more complicated than we given him credit for. There are many people who deserve more criticism for their role in colonialism than Malinowski (just wait for my blog post on Julian Steward). This is not to absolve Malinowski of whatever sins he committed. Rather, it’s just to ask that we remember what he actually did rather than project sins onto him.

The canonical author of the canonical book, naked black people, white guy in white clothes being White — for a lot of people, it’s totally crazy-making. But in many ways, Malinowski was far more more complicated than we given him credit for. There are many people who deserve more criticism for their role in colonialism than Malinowski (just wait for my blog post on Julian Steward). This is not to absolve Malinowski of whatever sins he committed. Rather, it’s just to ask that we remember what he actually did rather than project sins onto him.

For instance, it’s true that Malinowski did dress like this in the field. He was terrified of the heat and carefully followed ‘expert’ advice about how Whitemen should dress in the tropics. And yes, he was carried around on a chair in order to conduct a census although, as George Stocking sniffily notes, “in a stratified society like the Trobriands (where the chief sat upon a platform so that commoners ends not crawl on the ground in passing), “social parity”… is itself a rather problematic notion.”

The thing that most people don’t get about this picture is that at least 30% of it is cosplay. What surprises me about this image is that many people view it without any sense of irony — as if it had not been posed, as if Malinowski didn’t notice the difference between himself and ‘the natives’, as if Malinowski was unaware of what his lime spatula looked like.

The microsummary of Malinowski that I learned in graduate school was: “Good fieldwork methods, embarassing theory of functionalism”. The longer version added “Annette Weiner proved Malinowski was wrong because: gender” and “his diary proves he was a perv and shouldn’t be taken seriously.”

There is a lot of truth to this micro summary, including the critiques. But it also seriously underestimates Malinowski as a person and as a thinker. He was far more complicated.

Consider the following quotes:

“The science which claims to understand culture and to have the clue to racial problems must not remain silent on the the drama of culture conflict and of racial clash”

or

“There is no doubt that the destiny of indigenous races has been tragic in the process of contact with European invastion… The historian of the future will have to register that Europeans in the past sometimes exterminated whole island peoples; that they expropriated most of the patrimony of savage races; that they introduced slavery in a specially cruel and pernicious form; and that even if they abolished it later, they treated the expatriated Negroes as outcasts and paraiahs… The anthropologist who is unable to perceive this, unable to register the tragic errors committed at times with the best intentions, at times under the stress of dire necessity, remains an antiquarian covered with academic dust and in fool’s paradise.”

Or

“The whole concept of European culture as a cornucopia from which things are freely given is misleading. It does not take a specialist in anthropology to see that the European “give” is always highly selective. We never give any native people under our control – and we never shall, for it would be sheer folly as long as we stand on the basis of our present Realpolitik – the following elements of culture:

1. The instruments of physical power: fire-arms, bombing planes, poison gas, and all that makes an effective defence or aggression possible

2. We do not give out instruments of political mastery [i.e. sovereignty or voting rights]

3. We do not share with them the substance of economic wealth and advantages…. Even when under indirect economic exploitation… we allow the native a share of the profits, the full control of the economic organization remains in the hands of Western enterprise.

4. We do not admit them as equals to Church, Assembly, school, or drawing room… Full political, social and even religious equality is nowhere granted”

To be sure, Malinowski was a reformer, not a radical. And he was interested largely in colonial power in Africa, and he was interested in it because the Rockefeller Foundation was interested in it. But Malinowski was also Polish, and knew what it mean to have one’s country invaded by foreign powers. During his time in the Trobriands, he was technically a detained enemy combatant.

We should also not underestimate just what a freak Malinowski was. Consider, for instance, this exchange between John Comaroff and Isaac Schapera:

Schapera: I was his [Malinowski’s] research assistant… Malinowski was working on a book that he never published on the psychology of kinship, and used to lie naked, except for a modest piece of cloth covering his genitals. I had to scrub him down with medicine. There was a pail in which were various medicines, and I had a brush. It was something to do with his supposed sickness. But that is how he did his work.

Comaroff: So the relationships was more intimate with him, shall we say, than that with Radcliffe-Brown.

Schapera: Indeed.

Or consider this letter to Radcliffe-Brown himself:

We supermen need not stick to any conventions. My towering spirit and yours touch above the highest levels of microcosmic nebulas and there gaze in silence at one another.

This is how Malinowski apologized for not replying to letters promptly.

Over time our sense of the lives of famous anthropologists get flattened our and distorted. Its natural — arguing about their legacy is part of a political process, and over the decades details drop out. But sometimes I wish we could remember just how human and complex and — in Malinowski’s case — weird they were. Not in order to absolve them, but in order to see them how they really were. Anthropology is a discipline created by a person who had his RA’s rub him down with a brush. That means something. I’m not sure what. But something. A move vivid sense of history would be the first step, I think, in figuring out what.

Nice read. Looking forward to the Steward blog!

Be sure to check out this work on Steward.

https://muse.jhu.edu/article/252376/summary

Hear! Hear! Just yesterday I had a Chinese graduate student ask on Facebook why she was being trained to criticize early anthropologists before appreciating their positive achievements.

I would look into grammarly

Interesting article but I wonder if you thought about the following while writing:

I would start by carefully defining what you mean by ‘White Guys Doing Research’ – the phenomenon is valid but if you don’t tell us what you mean it seems like you are taking umbridge with the very fact.

You say about the picture that “at least 30% of it is cosplay” but again you don’t explain – what do you mean by cosplay, and why is that relevant? Who is conducting the cosplay?

I think the argument about Malinowski being weird is valid but unexplored. And to be honest, many of us ethnographers find ourselves doing ‘weird’ things in the field – I have been known to cover myself and help my friends cover themselves in sulphuric mud for up to 4 hours, a common practice among my interlocutors. I would probably avoid using that as evidence that I am in fact not racist. I would also argue that eccentricism is a privilege afforded more often to men and women, especially academics, and does not serve as a caveat for racist or discriminatory practices.

Additionally, and as an Eastern European myself, the argument that Malinowski was Polish and therefore could not be racist is not particularly impressive. I remind you of elements of Polish media and government’s involvement in creating anti-Islamic rhetoric both in their country and among their neighbours at present. Though the Poles do like many of us have a history of occupation, that does not necessarily extend to empathising on occupations of other races.

Finally – you argue that we need a better sense of our discipline’s history and I agree. However many anthropology departments do teach this history in order to educate contemporary students about anthropology’s role in the colonial endeavours of the past and indeed the present. I think retrospectively defining anthropologists as ‘weird’ serves to apologise for anthropology’s collaborations in occupations and oppression, even though I see that that is what you are trying to avoid here. You are right that we need to consider a holistic view of ethnographers and their actions, and documents like Malinowski’s diaries and an increasing amount of work post-reflexive turn, but it is also the ethnographer’s responsibility to provide evidence.

I don’t know about the controversy around Malinowski, and he might very well have been an asshole, but the comment on the picture seems so unfair – people from two cultures sit together, everybody following their own culture’s rules about how one should dress. Should he have engaged in cultural appropiation instead? Plus they didn’t even have good sunscreen then*, and leaving long-term damage aside, not wanting to get a sunburn on a skin not used to this much sun… does not make one a bad person. *according to statistics, skin cancer does vary by race https://www.cdc.gov/cancer/skin/statistics/race.htm

Anna thank you for your comments. You write that “the argument that Malinowski was Polish and therefore could not be racist is not particularly impressive”. This implies that I have argued that Malinowski could not be racist because he was Polish. However, I have made no such claim. Malinowski regularly refers to Papua New Guineans using the N word and Michael Young (his biographer) describes his horror at caste pollution as a major check on his libido in the field (lls). So I’m fine with saying Malinowski was racist while in the Trobes.

What I actually said was that Malinowski “knew what it mean to have one’s country invaded by foreign powers”. I suspect you agree with me that this is a true statement. Not only had Poland been partitioned during Malinowski’s life, but it was previously grievously affected by WWI. Malinowski was briefly arrested as a prisoner of war during his time in Australia. He feared for his mother’s life, and had only intermittent contact with her via post. It is for these reasons that I said that he knew what it mean to have one’s country invaded. It is easy to dismiss people as “the colonizer” but when we do this without explaining exactly what sort of colonizer they were in detail, we fail to do the work of critique and fall back on comfortable truisms that convince no one but ourselves. But critiques of him must actually be critiques of him in his particularity, just as critiques of me must take issue with what I have actually said 😉 Thanks for reading!

Good read!

One note:

Poland was invaded in 1939, Malinowski died in 1942, how exactly did he know “what it mean to have one’s country invaded by foreign powers” and how does that go into his writing and thought?

Francisco: Poland was partitioned by foreign nations in 1772 and for over a century was a nation without a state. Malinowski was born and raised a subject of the Austro-Hungarian empire.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Partitions_of_Poland

His last book, Freedom & Civilization is a justification of Democracy and a critique of fascism and totalitarianism. If you’d like to know more about him, I’d suggest starting with the wikipedia page on him — it’s not bad!

This is a cool article on BM too

https://books.google.ca/books?hl=en&lr=&id=hG5oBAAAQBAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PA69&dq=Lamont+Histories+of+anthropology+annual+malinowski&ots=2Meqojt6ki&sig=G6egvVZlYaW1PawXbv_Hu1WHNcY#v=onepage&q&f=false