This two-part post is a collaborative authorship between Taylor R. Genovese and Martin Pfeiffer, a PhD student in Anthropology at the University of New Mexico. For more on Martin’s work see his blog Deus Ex Atomica and his personal Twitter account @NuclearAnthro.

Introduction

Beginning in 1966, millions of people around the world (including the authors) have settled in front of the warm glow of a television or movie screen to watch an intrepid crew of space explorers venture through the cosmos—not for reasons of invasion or extraction, but for the more virtuous purpose of simply going where no human has ever been. We are of course talking about watching Star Trek. As we grew up and learned more about human “space exploration,” our understandings remained consistent with the dramatic imaginary of Star Trek: that adventuring into the cosmos is an inherently noble goal, pursued by good people, for inherently noble reasons. Space was the “final frontier” and humanity strode out into that glittering darkness as a matter of destiny, not conquest. Formal education during our college years initially added little nuance to our opinions about human space exploration. Sure, the space race was part of the Cold War “competition” with the Soviet Union, but “space exploration” remained pure and good in our minds.

Graduate school, that Eater of Dreams, began to change our conceptualizations as we dug deeper into these subjects. As part of Martin’s coursework at UNM, he has engaged in ethnographic and archival research including collecting nuclear weapon laboratory and defense advertising from Physics Today and Scientific American between the years of 1950-1964. Meanwhile, Taylor spent his MA years ethnographically investigating humanity’s changing perceptions of the cosmos, particularly in how the rapid commercialization of space affairs was shifting our cosmic goals from exploration to exploitation. As we brought our separate research endeavors into conversation with each other, we began to realize the imbricated natures of U.S. projects and discourses of nuclear weapons and space development.

We make three major arguments based on our fieldwork and collaboration. First, “space” was, and remains, a slippery and nebulous term. Rather than “space” it is better, we argue, to instead speak of “spaces” that range from atomic to extra-planetary: nuclear, oceanic, atmospheric, Earthly, and outer spaces.1 Second, spaces “exploration” often was, and still is, explicitly conceptualized and discussed through gendered and colonial vocabularies of military advantage and frontier conquest. Third, spaces technologies and nuclear technologies were, and are, intimately connected through technoutopian imaginaries and discourse. In this two-part post we will focus on the capitalist and militaristic slippages of supposedly separate domains into “spaces” and the connections of nuclear and spaces technology as a technoutopian imaginary.

Space(s) Exploration: Peace through Knowledge!

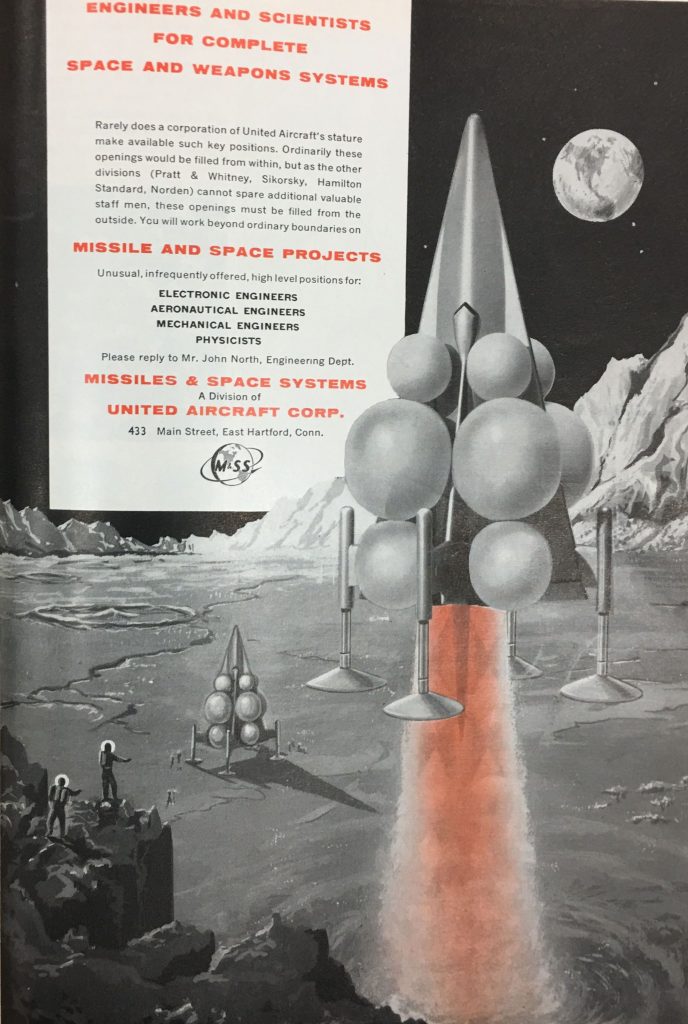

This United Aircraft Corp advertisement, published in 1959, hints at the broad outlines of our arguments and data. It partially demonstrates the practical day-to-day overlap of skill sets involved with spaces and U.S. (nuclear armed) military missile development; the recurring appeals to an unrealized, but better, future brought about through technological conquest of a frontier; and the corporate, profit-driven entanglements of American businesses in military and spaces projects.

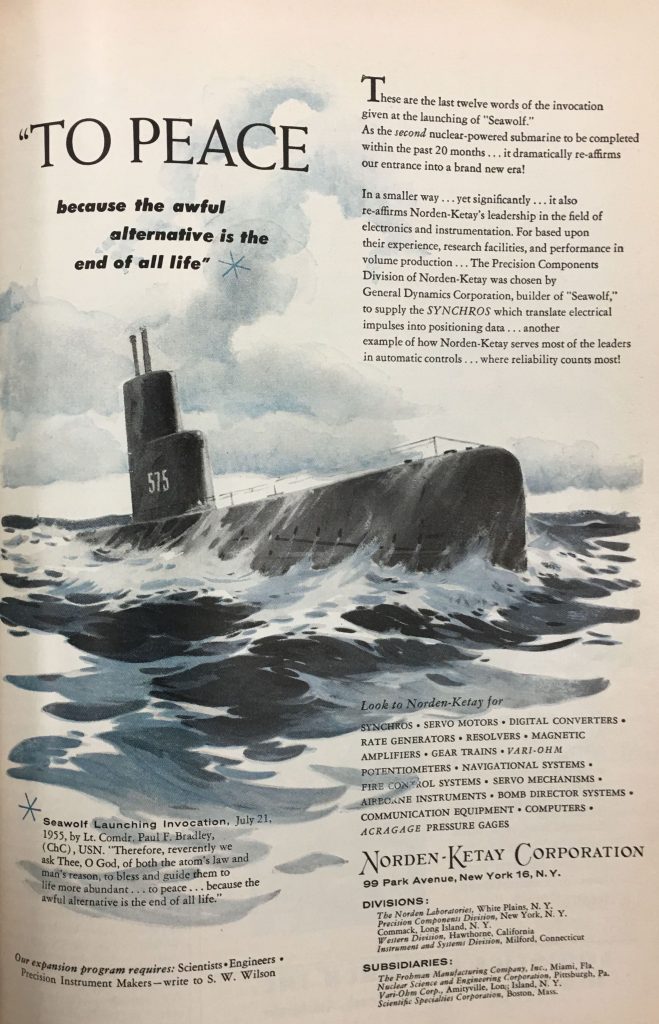

In an expansion on these themes, a 1955 advertisement (below), highlighting Norden-Ketay’s work on the second U.S. nuclear propelled submarine, exemplifies a post-WWII technoutopian restatement of the meliorist & Apocalyptic Enlightenment traditions. Technology, and spaces exploration, becomes salvation from, and by, threat of destruction. The services listed in the ad reveal the overlap of civilian-military technological advancement: “servo motors,” “navigational systems,” “fire control systems,” “communication equipment,” and “computers.”

The post-WWII period was, arguably, an unprecedented period in human history in terms of both the development of technology and the harnessing of those tools—in the names of “science” and “security”—to discover and control human environments. The United States undertook numerous large-scale, high-tech, and expensive projects to generate legible data about the Earth, oceans, atmosphere, and outer spaces. These projects, as the Aerojet-General (1962) advertisement below demonstrates, were often publically imagined as “vitally important to man’s [sic] future—scientific, economic, military” (11).

The Aerojet-General advertisement also offers examples of the conceptual slippage from “space” into “spaces” and the recurrent discourses of technomediated frontier conquest and exploitation. The “world of inner space” is “[a]lmost as unexplored as the regions above the earth’s atmosphere” and Aerojet-General is “a pioneer in undersea technology . . . focused . . . on the sea and its potential” (Aerojet-General 1962). The“[u]nderwater intelligence” referred to by Aerojet-General included hydroacoustic technology and oceanic maps developed in the United States significantly out of military concerns for keeping American submarines hidden while tracking Soviet naval forces.

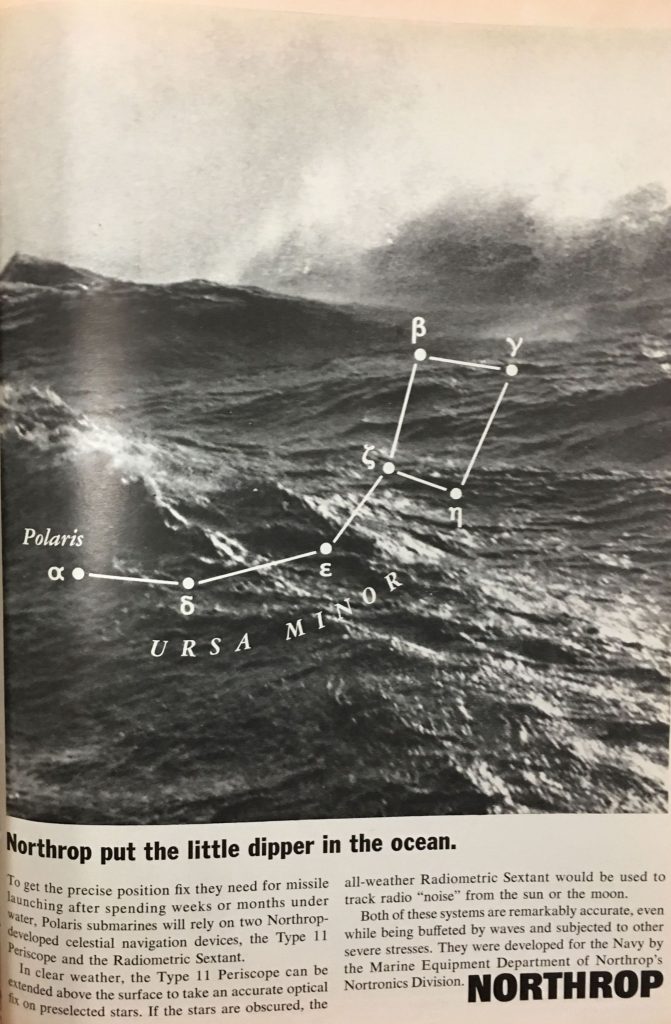

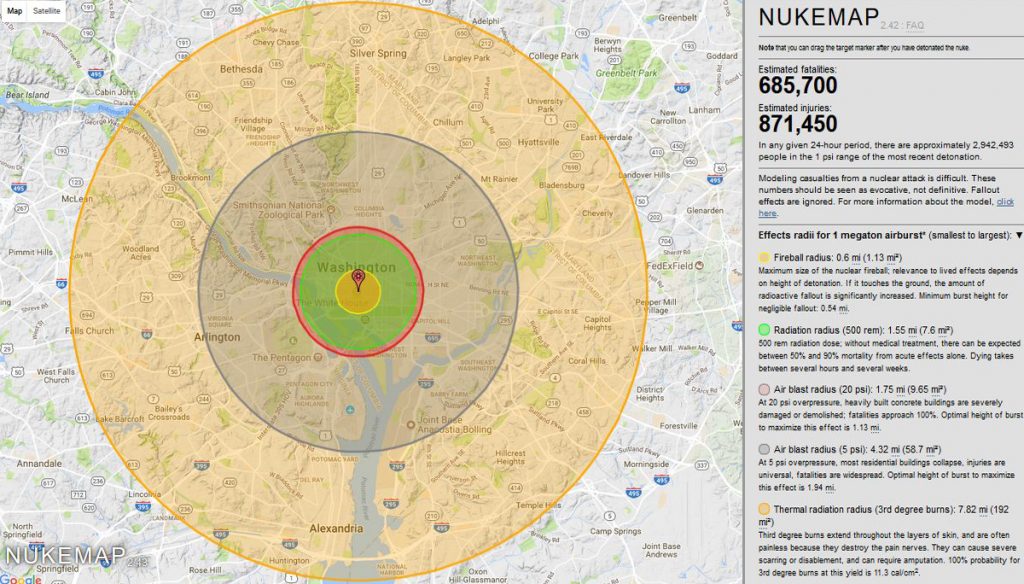

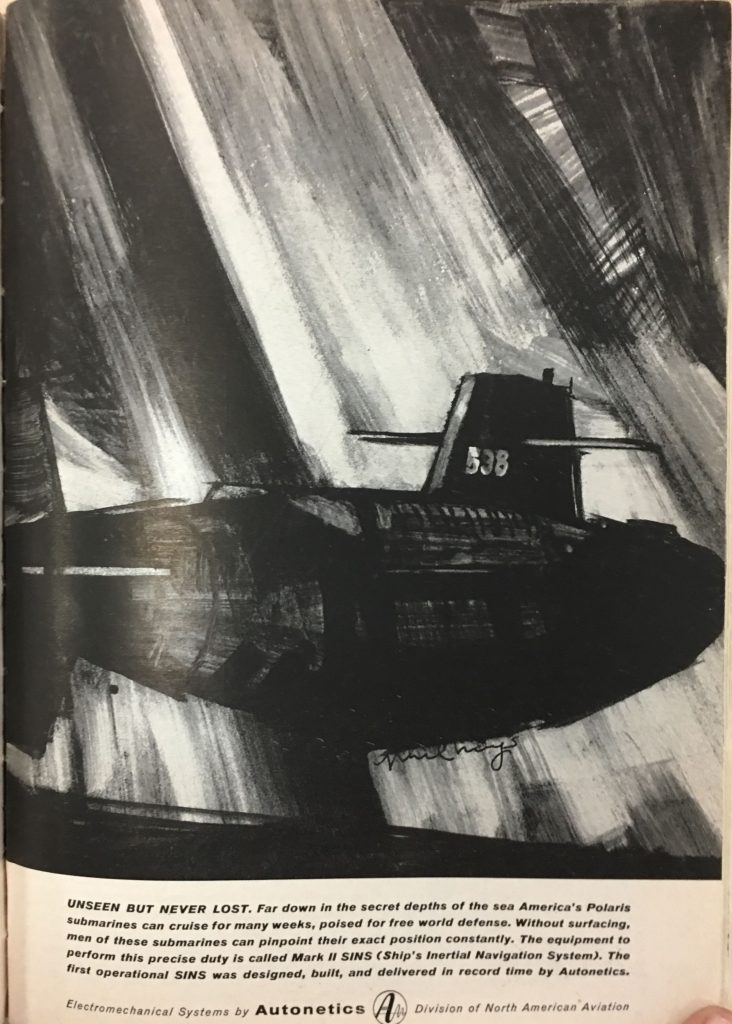

Similarly, a 1962 Northrop ad (above) graphically and textually articulates militarized spaces knowledge across the domains of inner and outer. Nuclear propelled U.S. Polaris missile submarines—to maintain desired levels of both stealth and accuracy—relied on multiple spaces knowledge including atomic, astronomical, oceanic, and Earthly (MacKenzie 1993). The early U.S. ballistic missile submarines each carried sixteen Polaris A-1 missiles armed with W47 nuclear warheads of either 600 kilotons or 1.2 megatons yield (Polmar and Norris 2009, 56). The following map simulates the airburst detonation of a one megaton nuclear weapon on Washington D.C. (Wellerstein 2017).

The ability of each Polaris missile submarine to draw on cross-spaces knowledge to “pinpoint their exact position constantly” allowed each vessel to be “poised for free world defense” by being able to accurately launch their nuclear-tipped missiles against cities and, if we are being charitable, maybe soft-military targets (Autonetics 1961).2

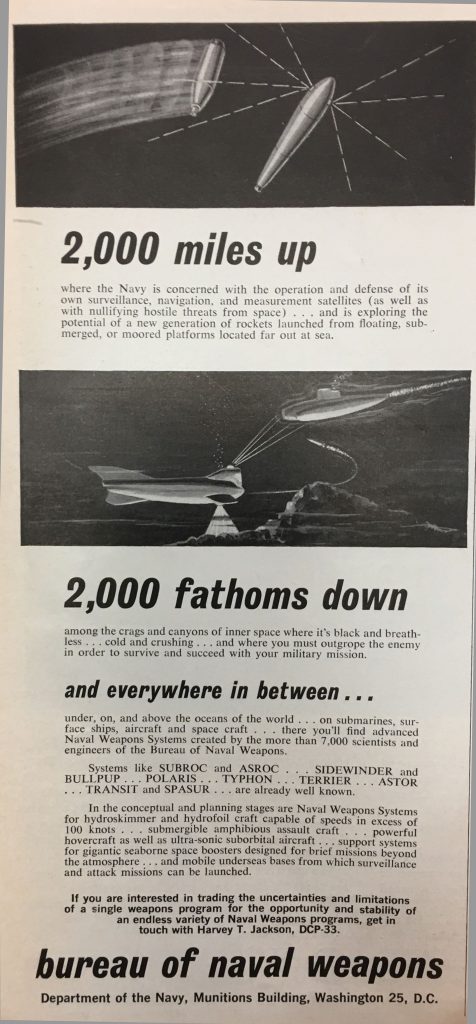

An additional advertising example, from the Bureau of Naval Weapons (1963, below), points to how military actors explicitly and publically theorized cross-spaces knowledge as critical to U.S. supremacy. The title of the advertisement—“2,000 miles up…2,000 fathoms down”—prefigures contemporary U.S. military conceptualizations of integrated and cross-domain deterrence and warfare: from cyberspaces to outer spaces!

Spaces of Nuclear Technoutopianism

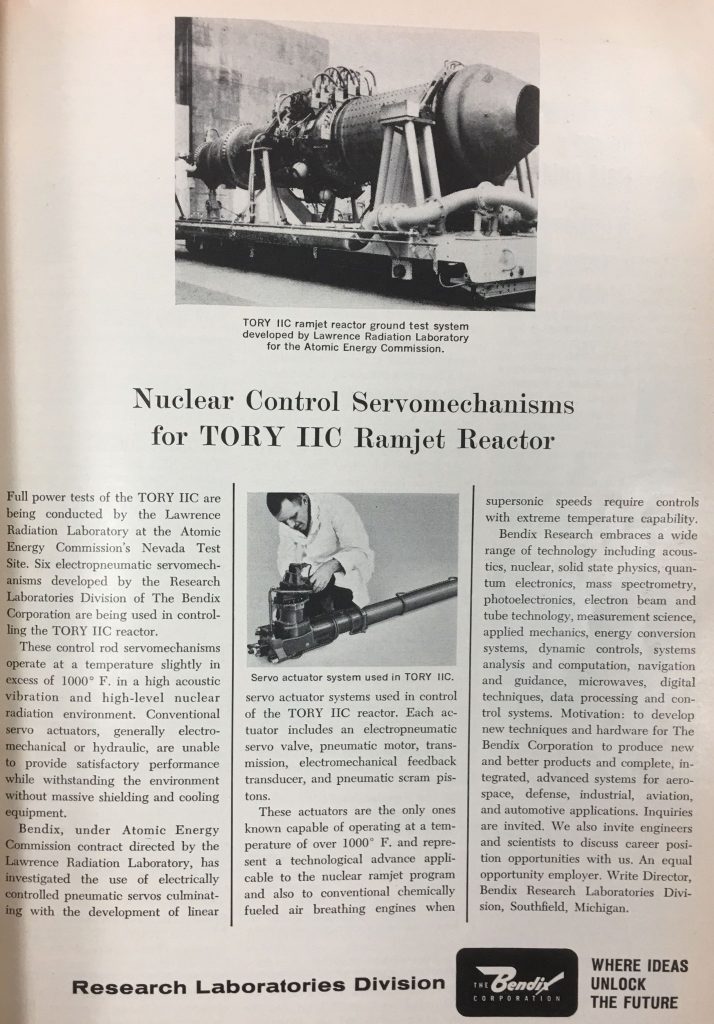

A 1960 Bendix ad (below) provides additional examples of euphemistically cheery slippages from “space” to “spaces” along with expressions of militarized nuclear technoutopianism. Its text reads “[i]n the all-out race for space and air supremacy the United States is developing three mighty nuclear engines—a nuclear aircraft engine, a nuclear ramjet and a nuclear rocket engine” (Bendix 1960). In this imaginary, American military and scientific supremacy springs from the control and regulation of technological knowledge across a scale of spaces, from “the atom-splitting, heat-producing process” to the “tremendously increased range” of the supposedly inevitable nuclear-powered missiles.

Particularly discordant with the glibly stated desire for American “supremacy” in this advertisement is mention of the nuclear ramjet engine that was intended for Project Pluto (see ad below). Project Pluto sought to construct what can be fairly termed a Doomsday Weapon: a supersonic nuclear powered cruise missile loaded with multiple nuclear warheads and spewing lethal radiation along its flight path (Polmar and Norris 2009). Gregg Herken perhaps put it best when he characterized Pluto as “[a] locomotive-size missile that travels at near treetop level at three times the speed of sound, tossing out hydrogen bombs as it roared overhead” (Herken 1990, 28).

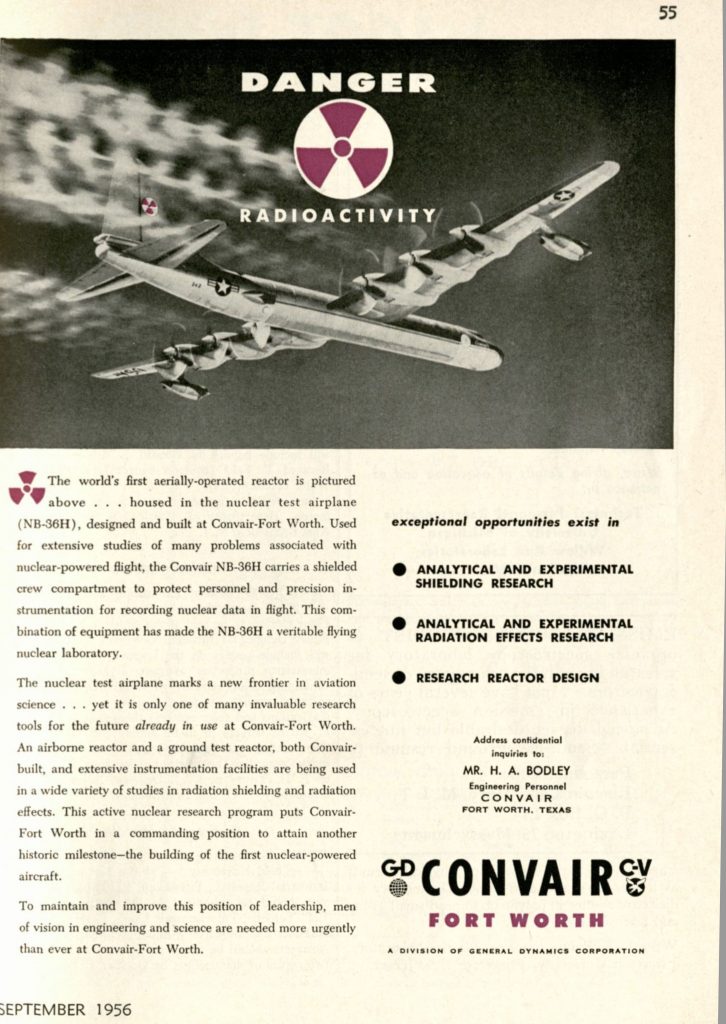

Similarly baroque and militaristic uses were imagined for aircraft nuclear propulsion. The U.S. Aircraft Nuclear Propulsion (ANP) project focused on the development of a nuclear powered bomber of virtually unlimited range and unprecedented payload capability. One John F. Kennedy official, upon discovering the project was still funded, supposedly compared the experience to “coming downstairs in the morning and finding a dead walrus in your living room” (Polmar and Norris 2009, 73). Testing for the ANP program in the 1950s included a modified B36 bomber flying more than 40 missions over the continental United States with an operational—and often running—three megawatt nuclear reactor. Convair, in the ad below, highlighted its ANP work and engaged colonially gendered language to move seamlessly between military and scientific purposes of spaces exploration as it proclaimed a need for “men of vision” to make use of “tools for the future already in use at Convair Forth Worth.”

In Part 2, we continue our discussion with deeper theoretical engagement of spaces exploration and technoutopianism.

References

Aerojet-General Corporation. 1962. “Ocean: Vast Vital Virtually Untapped.” Scientific American 206 (3): 11.

Autonetics. 1961. “Unseen but Never Lost.” Scientific American 205 (3): 95.

Bendix. 1960. “Three Nuclear Engines in Race for Air-Space Supremacy.” Scientific American 202 (3): 6.

———. 1964. “Nuclear Control Servomechanisms for TORY IIC Ramjet Reactor.” Scientific American 211 (1): 137.

Bureau of Naval Weapons. 1963. “2,000 Miles Up…2,000 Fathoms Down.” Scientific American 208 (4): 194.

Convair. 1956. “Danger Radioactivity.” Physics Today 9 (9): 56.

Herken, Gregg. 1990. “The Flying Crowbar.” Air & Space Magazine 5 (1): 28.

MacKenzie, Donald. 1993. Inventing Accuracy: A Historic Sociology of Nuclear Missile Guidance. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Norden-Ketay Corportion. 1955. “To Peace, because the Awful Alternative is the End of All Life.” Scientific American 193 (6): 23.

Northrop. 1962. “Northrop Put the Little Dipper in the Ocean.” Scientific American 206 (5): 145.

Oman-Reagan, Michael P. 2015. “Unfolding the Space Between Stars: Anthropology of the Interstellar.” In 114th Annual Meeting of the American Anthropological Association. Denver, Colorado: American Anthropological Association.

Polmar, Norman and Robert S. Norris. 2009. The U.S. Nuclear Arsenal: A History of Weapons and Delivery Systems since 1945. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press.

United Aircraft Corp. 1959. “Engineers and Scientists for Complete Space and Weapons Systems.” Scientific American 200 (5): 137.

Wellerstein, Alex. 2017. “Nukemap.” Restricted Data: The Nuclear Secrecy Blog. https://nuclearsecrecy.com/nukemap/?&kt=1000&lat=38.8970394&lng=-77.0361841&hob_ft=0&casualties=1&zm=11, accessed 07/11/2017.

- In this way, it is perhaps somewhat similar to the argument—made by Michael Oman-Reagan—that we should begin to think of outer space as a process instead of as a place. Oman-Reagan (2015) has also written about the linkages between outer and oceanic spaces. ↩

- “Hard” and “soft,” “military” and “civilian” or “urban-industrial” targets are imprecise categories. Soft targets can include things like civilian housing and construction, military administrative centers, and often airfields. Hard targets are constructed in such a way as to resist nuclear effects and often include things like underground command bunkers and missile silos. Early deployments of Polaris missiles were relatively inaccurate and probably targeted against comparatively soft targets like cities and/or unhardened military facilities. U.S. deployment of Trident C-4 and Trident II D-5 missiles led to ballistic missile submarines being able to more efficiently target hardened facilities. For an idea of the effects of 600 kilotons, see Alex Wellerstein’s informative simulator, Nukemap. ↩