In the waning moments of 2016, one man, armed with an AR-15 and “information” about a conspiracy related to Hilary Clinton, walked into a DC pizza parlor hell bent on finding truth. After a quick look around and a shot or two fired, what he got was arrested. This is surely an extreme example of the perils of “dangerous nonsense” that Neil Postman warned us about decades ago.

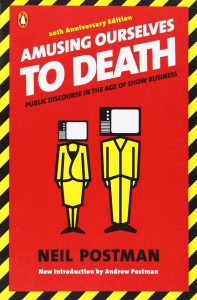

Back in 1985 Postman wrote a little book called “Amusing Ourselves to Death,” which I happened to use for a class on culture and film I was teaching last year. It turned out to be a prescient book to be reading during the 2016 campaign season (and then some). Postman’s book focuses on the erosion of public discourse in the US, and he faults TV as one of the primary corrosive forces. While there are admittedly some holes in his argument, especially from an anthropological perspective,[1] the book is definitely worth a read.

Back in 1985 Postman wrote a little book called “Amusing Ourselves to Death,” which I happened to use for a class on culture and film I was teaching last year. It turned out to be a prescient book to be reading during the 2016 campaign season (and then some). Postman’s book focuses on the erosion of public discourse in the US, and he faults TV as one of the primary corrosive forces. While there are admittedly some holes in his argument, especially from an anthropological perspective,[1] the book is definitely worth a read.

In essence, Postman’s book is about the fate of liberal democracy. He begins the book with a simple suggestion: If we want to understand what has happened to our democratic institutions, we should look to Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World rather than George Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four (the latter, of course, is selling like crazy in these post-election times). Postman writes,

Contrary to common belief even among the educated, Huxley and Orwell did not prophesy the same thing. Orwell warns that we will be overcome by an externally imposed oppression. But in Huxley’s vision, no Big Brother is required to deprive people of their autonomy, maturity and history. As he saw it, people will come to love their oppression, to adore the technologies that undo their capacities to think.

Arguably, Postman may lean a bit toward the deterministic side when it comes to technology’s effects on human behavior. Some of my students in the culture and film class expressed this criticism, and to an extent they may be right. Several commented that it sounded like Postman felt that TV and other technologies simply brainwashed people into doing and thinking in certain ways–as if there is no choice or agency. It’s a good critique to keep in mind. At the same time, I think it’s important to note that Postman may be a bit hyperbolic in his argumentation in order to drive his point–or warning–across to readers.

Much of what he argues is meant to get us thinking about things we may or may not want to think about on a day to day basis. Do technologies that undo our capacity to think? What kind of nonsense is that? How could any technology do such a thing? By the way, if you need to check your mobile phone because it’s been more than 30 seconds, now would be a good time. It’s ok, I won’t judge. In fact, I checked my email 47 times while writing this post.

Are you still with me? Good. It’s hard not to let all of this media get in the way of what we’re trying to do here. And I think that’s part of Postman’s point, which is less about the brainwashing power of TV and more about the broader effects of media and how it shapes our understandings of and engagements with the world around us. The problem, back in the 1980s, wasn’t that TV shows like Dallas or even Sesame Street were turning American brains into mush, but that people en masse became used to receiving information and ideas in that passive format. He was particularly concerned with the idea that the medium of television would ultimately displace other forms of truth, or even the desire to seek truth at all:

What Orwell feared were those who would ban books. What Huxley feared was that there would be no reason to ban a book, for there would be no one who wanted to read one. Orwell feared those who would deprive us of information. Huxley feared those who would give us so much that we would be reduced to passivity and egoism. Orwell feared that the truth would be concealed from us. Huxley feared the truth would be drowned in a sea of irrelevance.

A sea of irrelevance. Imagine that.

Postman’s bet is that Huxley, rather than Orwell, was right. His primary argument is that the content of public discourse has become so flooded, so degraded, and so trivialized that it is little more than “dangerous nonsense.” Now, it would be easy to see Postman as some neo-Luddite who abhors technology and blames it for everything that is wrong with society. More than a few of my students read him in this light. But I reminded them—and now you—that there was more to his argument. Without getting into too many details, one of the key points that Postman makes, clearly borrowing from and building off of the work of Marshal McLuhan, is that real issue we need to pay close attention to is how any particular medium—in this case TV—affects human discourse, learning, and communication. In other words, The Medium is the Message.

What does this mean? Postman’s argument is that it’s not content per se that concerns him, but rather the process through which content is produced, shared, and ultimately digested by audiences. What matters is how a given medium shapes, limits, and transforms the very possibilities of knowledge production. For Postman, the TV commercial is a perfect symbol of what has happened to public discourse. Compared to the long, drawn out public debates of the 19th century, Postman argues, contemporary political debate has basically been reconfigured to fit the norms of TV commercials: brief, simple, appealing, and, most importantly, entertaining. Political campaigns and TV news, Postman says, have for the most part become little more than a bunch of entertaining, attention-grabbing, context-free TV commercials, and the worrisome issue is that viewers seem to have lost the capacity to notice the difference (keep in mind that this was written in the mid-1980s).

Postman quotes the late Ronald Reagan, who back in 1966 said “Politics is just like show business.” In this new media saturated game, Postman explains, what matters above all is appearance. Truth matters less than appearing truthful, he says. A TV commercial, Postman tells us, isn’t about the product as much it’s about the audience, the viewers. As we sit there on our couches, tuned into CNN or MSNBC or Fox News, it’s all about us. As we browse through the onslaught of bad GIFs, news stories, gossip, personalized Twitter and Facebook feeds, emails, texts…it’s about us, the viewers. As Postman writes,

This is the lesson of all great television commercials: They provide a slogan, a symbol or a focus that creates for viewers a comprehensive and compelling image of themselves. In the shift from party politics to television politics, the same goal is sought. We are not permitted to know who is best at being President or Governor or Senator, but whose image is best in touching and soothing the deep reaches of our discontent.

How does this relate to the media-saturated environment many of us live in today? We watch continuously. We tune in all day long. We’re connected at all hours, constantly checking to see what we’ve missed. This barrage, tailored for us, made to sooth and appeal to all of us as a unique mass of individual consumers, comes to us in various entertaining, amusing forms. We like things on Facebook, we share pleasant, funny stories on Facebook. Postman argues that amusement, above all, reigns…and this is no accident:

Tyrants of all varieties have always known about the value of providing the masses with amusements as a means of pacifying discontent. But most of them could not have even hoped for a situation in which the masses would ignore that which does not amuse. That is why tyrants have always relied, and still do, on censorship. Censorship, after all, is the tribute tyrants pay to the assumption that a public knows the difference between serious discourse and entertainment—and cares. How delighted would be all the kings, czars and führers of the past (and commissars of the present) to know that censorship is not a necessity when all political discourse takes the form of a jest.

The real problem is when audiences can’t discern the different between the “jest” and reality, and when one effectively becomes the other. Or, perhaps worse, when people are willing to do and say anything to get attention, and audiences just lap it up (especially if it confirms what they already believe). Remember when Trump said he was “just joking” when he called for Russia to find Hillary’s emails? Or when Richard Spencer said his threats of an armed neo-nazi march were just a joke? They’re all just joking. Much of the political rhetoric these days gets written off as a joke, satire, or “just being ironic”. Even Alex Jones is now arguing that people can’t take what he says too seriously because he’s just a “performance artist.”

Isn’t is all so amusing? No, actually, it’s not. Especially when media is increasingly used as a tool for fomenting hate, division, and violence not only in the US, but around the world.

So what does anthropology have to do with all of this? Find out soon in Part 2.

To be continued…

[1] Postman’s use of the “culture” concept is particularly problematic from an anthropological perspective, as is reliance on the idea that the written word expresses the highest form of human thinking and achievement. His argument is pretty hostile to visual culture in a broad sense, and also dismisses the importance of the ways in which ideas and history were maintained and disseminated long, long before writing was invented. Postman’s argument would benefit from a broader, more historical and anthropological approach to knowledge and media production, one that includes the oral, the written, and the visual all at once. Still, despite its flaws, his analysis is thought-provoking and valuable.

Aye… Indeed… etc… But was there ever an age without its dangerous nonsense? Perhaps the ages before humans arrived? Our wisdom and our nonsense seems to have developed hand in hand.

Ya Andrew, you’re probably right that there never was an age without dangerous nonsense. The title is just pulling from Postman’s terms, but you’re right that this isn’t necessarily a novel problem. Perhaps it’s the particulars of the problem that are the issue–the role of TV in Postman’s time and, these days, the unwieldy wonders of the internetz.

Two things might be worth looking at together: (1) the similarity between current and previous, e.g., 19th century, moral panic in the face of accelerating, technology-driven change, and (2) the possibility that the panic is now less paranoid and the critical concerns more apt since the pace of change is, indeed, accelerating.