Conclusion: It’s all fun and games…

As I mentioned in the first post of my series, anthropologists and ethnobiologists have played an outsized role in studying and popularizing ayahuasca and Amazonian shamanism, and more recently, attending to its internationalization. This history affords anthropologists a stake in discussions of drug policy issues pertaining to the subjects; one might even suggest it requires their participation as a matter of ethical concern. One topic of interest among scholars and activists right now is whether and how to regulate ayahuasca practices within a framework of increasing legalization and legitimation in the global north. Some scientists and activists seem to believe that legality alone will bring increased transparency and safety by eliminating the need for practitioners and participants to navigate in what is effectively a criminal underground. However, the assumption of legality among the practitioners and participants of the new ayahuasca churches, particularly Ayahuasca Healings, sheds light on numerous other problems that legalization alone will not solve—in fact, may exacerbate. These include the misappropriation of indigenous culture, the hyper-commodification of spirituality, and a rapid increase in demand for the vine, which is already being overharvested in some areas.

As we saw in post #6, a major issue that arises in the face of legalization is how to ensure the physical and psychological safety of participants and the qualifications of practitioners—an issue which remains problematic even in the Amazon. How would ayahuasca practice be regulated and policed if it were legalized in North America—or should it be? Scholars and researchers are beginning to discuss options for such a scenario (Blainey 2015; Haden et al. 2016). However, given the privileged role of religion in U.S. culture and the lack of regulatory oversight of religious organizations and their leadership, even in the face of some of the nefarious practices associated with religion in our country, it is questionable whether legalization under the rubric of religious freedom will provide for the safety and wellbeing of participants—especially given the rise of these new ayahuasca churches, their often young and inexperienced leaders, and the DEA’s lack of regulatory powers with regard to the level of training and experience of “ministers” or “clergy.”

Contributing to this issue is the lack of discernment engendered by anything-goes New-Age eclecticism and the emotional neediness—and therefore, vulnerability—of a population scarred by the excesses and violence of modernity. Such a population is easy prey for a charismatic leader promising transformation, awakening, and freedom. While such leaders, and the dangers they represent, are not confined to ayahuasca shamanism, it may be that ayahuasca use exacerbates the problem. Despite the common wisdom that ayahuasca “dissolves the ego,” the very opposite may be true. One gringo shaman that I know calls it “the ego explosion.” “We warn people about it when they come to visit our center,” he said. The UDV has systems of accountability in place that help keep a lid on excessive egotism and ensure acceptable behavior from leaders and members. Traditionally, the egalitarian social structure of Amazonian culture has performed the same function. However, with the expropriation of ayahuasca use to new cultural settings, particularly the Western world where personal freedom and individuality are cherished above all, social controls over individual transgressions are in short supply. Thus the privileged position of religious freedom in U.S. culture, along with the premium placed on individual freedom, are a recipe for danger when it comes to the legalization of ayahuasca within the current framework.

Whether or not Ayahuasca Healings succeeds in winning their DEA exemption—and most observers believe that they won’t—the controversy has exposed the ongoing rift between the neo-shamanism community in the United States, which invariably lays claim to romanticized images of Native American and indigenous Amazonian spirituality and worldviews, and various sectors of the Native American community, in this case, the Native American Church. It is a humorless irony that the new ayahuasca churches purportedly idolize and seek to mimic those very Native American peoples who have consistently denounced such misappropriation of Native American spirituality and culture, and who have so consistently and vehemently distanced themselves from James Mooney and ONAC.

The disjuncture is not just between New Age and Native American spirituality, but also between Amazonian and Native North American forms of shamanic and religious practice, colonial histories and socioeconomic settings. Contemporary ayahuasca shamanism evolved in a context of interethnic travel and trade. Shamanic power in the Amazon relies on the ability to live, act, communicate, and negotiate across the boundaries between various groups of humans, between human and non-human, and between material and spiritual worlds. Kinship and personhood among indigenous Amazonians are based more on relations of nurturance and reciprocity than on genetic speciation. Jaguars, for example, may be considered people, even kin, whereas members of other tribes may be considered not fully human. Within the field of genetically human relationships, where the social structure is based on colonial ethnic hierarchies, the use of ayahuasca is used variously to index ethnic distinctions, to subvert them, and to blur them in the process of interethnic alliance building. Ethnicity in the Amazon tends to be fluid. This cosmopolitanism, the cross-boundary exchange and multi-ethnic eclecticism that characterizes Amazonian shamanism has made it a good fit for an international audience. Furthermore, due to the interethnic nature of Amazonian shamanism, services have historically been rendered for a fee. This practice was readily expanded to incorporate the current wave of seekers to the Amazon.

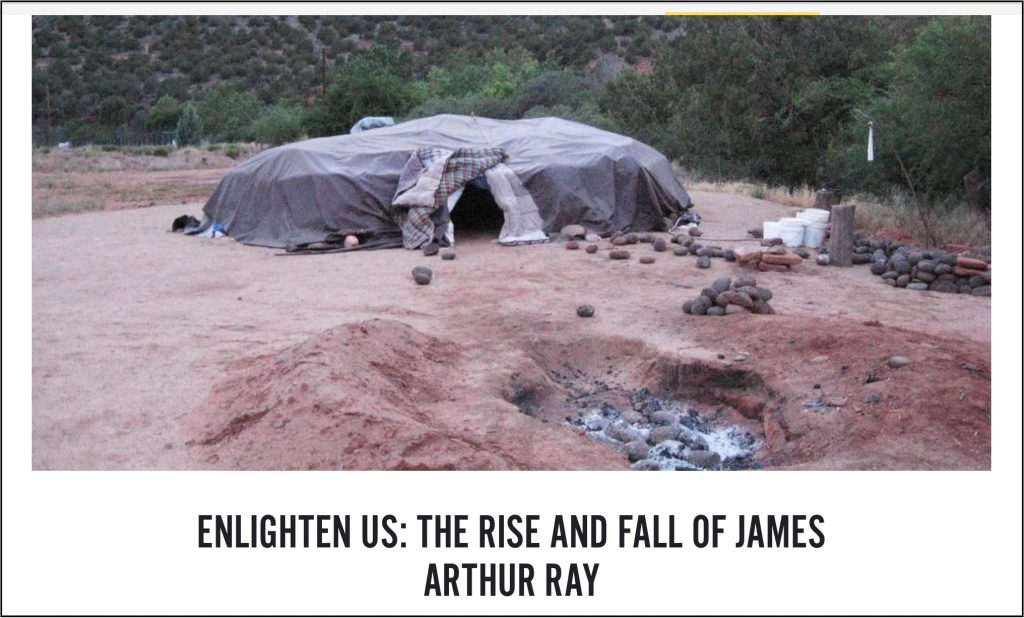

In North America, however, ayahuasca shamanism has been juxtaposed onto an indigenous context that is completely anathema to the commodification of anything spiritual, and in which ethnicity is far from fluid. In Native North America, ethnic identity is measured by blood quotient and by registration in a federally recognized tribe, and identity politics are a serious issue with very real ramifications for tribal membership and access to the benefits that it affords. Furthermore, New Age appropriation of indigenous spirituality has been a sore spot for Native American people for decades, and even inter-tribal appropriation (e.g. the Sun Dance and sweat lodge ceremonies), as well as the sale of native spirituality by indigenous people to outsiders, have led to bitter acrimony within the Native North American community (Churchill 2003).

Equally salient are the different religious and colonial contexts that predate contemporary indigenous spirituality in North and South America. Ayahuasca shamanism developed largely within the socio-cultural and economic context of Jesuit missionization, which was relatively tolerant of shamanic practice, even incorporating it into the Jesuit system of indirect governance. Similarly, Amazonian healers often eagerly adopted the symbols and imagery of their powerful Christian counterparts. Some scholars claim that the ayahuasca ceremony itself is a hybrid form born within the missions that later spread to the hinterlands (Gow 1994). To the contrary, Native North American peoples still remember vividly the missionary boarding schools to which their grandparents were abducted, where they were violently stripped of their families, their languages, and their cultures. They also remember vividly the centuries of persecution that they suffered for the practice of their religions. The passage of the American Indian Religious Freedom Act and the Religious Freedom Restoration Act have only begun to repair this damage, and yet it is these hard-fought and long-suffered victories to which proponents of New-Age indigeneity now lay claim.

One one level, the Ayahuasca Healings story is just one example of many in which non-indigenous people seek to appropriate indigenous culture and in so doing, colonize the territory of the spirit in the same way we have colonized their lands. On another level, the Ayahuasca Healings story is one of youth, idealism, and naiveté, coupled with a millennial culture of narcissism, self-promotion and entrepreneurialism, inflamed by the runaway egotism that appears to be a possible side-effect of frequent ayahuasca use. On all levels, however, the story is a cautionary tale about the practical, ideological, and ethical problems that confront the legalization of ayahuasca, problems that the current framework, based on a religious-freedom exemption, fails to address.

Author’s note: Thanks to Jade Grigori for help with wording. Also thanks to the editors and April guest blogger of Savage Minds for allowing me to overstay my welcome and continue posting until the story was complete.

Works Cited:

Blainey, Marc G. 2015. “Forbidden Therapies: Santo Daime, Ayahuasca, and the Prohibition of Entheogens in Western Society.” Journal of Religion and Health 54(1):287-302.

Churchill, Ward. 2003. “Spiritual Hucksterism: The Rise of the Plastic Medicine Men.” In Shamanism: A Reader, edited by Graham Harvey, 324–333. New York: Psychology Press.

Gow, Peter. 1994. “River People: Shamanism and History in Western Amazonia.” In Shamanism, History and the State, edited by Nicholas Thomas, and Caroline Humphrey, 90–113. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan.

Haden, Mark, Brian Emerson, and Kenneth W Tupper. 2016. “A Public-Health-based Vision for the Management and Regulation of Psychedelics.” Journal of Psychoactive Drugs 48(4):243-252.