How do planetary scientists understand distant places like Mars or planets orbiting another star? A conversation with Lisa Messeri about “resonance” and the anthropology of space.

By Michael P. Oman-Reagan

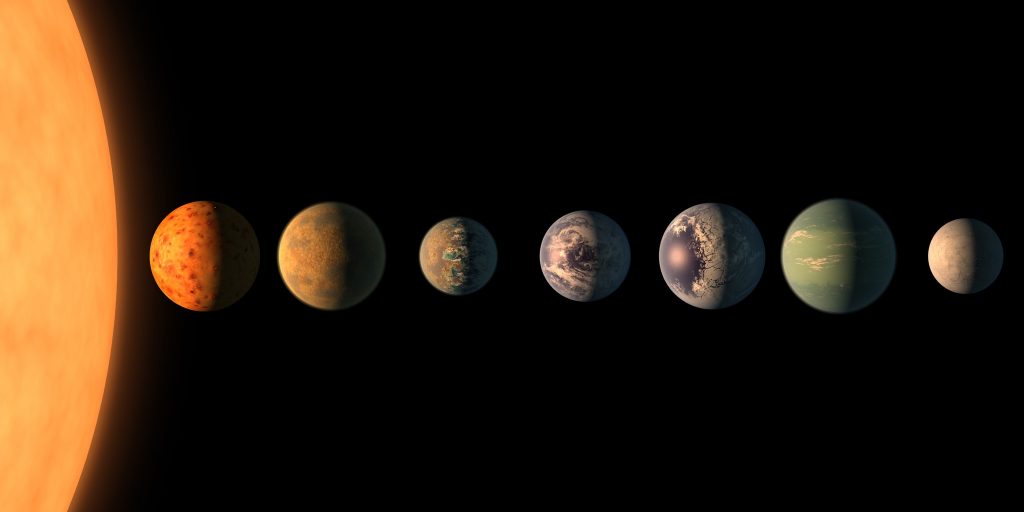

Yesterday, NASA announced the discovery of seven Earth-sized exoplanets (planets outside of our solar system) orbiting the star TRAPPIST-1. This is the most known rocky planets around a single star and, as planetary scientist Sara Seager noted in yesterday’s press conference, that makes this system an ideal laboratory for understanding if any of these planets host truly Earth-like conditions. Last May, scientists using the Transiting Planets and Planetesimals Small Telescope (TRAPPIST) in Chile announced they had found three planets in this system. Yesterday’s letter, published in Nature, confirmed the historic discovery of seven planets in the TRAPPIST-1 planetary system.

In an article out this month in American Ethnologist, “Resonant Worlds: Cultivating Proximal Encounters in Planetary Science,” anthropologist Lisa Messeri draws on her fieldwork with planetary scientists to propose new ways of thinking about how they “recognize the alien in the familiar” as they study planets in our solar system like Mars and as they search for exoplanets. In this post, Messeri and I discuss her findings and insights about human engagements with space, science, and anthropological ways of finding a connection to seemingly distant other worlds.

“It is a rare occurrence when researchers experience complete resonance—a profound connection to what they have encountered, one that facilitates a deeper understanding of something that might not actually be present.” -Lisa Messeri

Michael Oman-Reagan: In your new article you describe how anthropologists have looked at the ways scientists use visualization and embodiment to make the seemingly invisible more visible, whether they’re dealing with the molecular scale as in Natasha Myers’ work or like Stefan Helmreich’s work on waves as scientific things. Now, you’ve suggested another way scientists engage with distant objects of study, resonance, a concept you note has been used in acoustics, physics, and in ethnography. But you have a specific and fascinating insight here about the ways resonance works for planetary scientists, and how it’s different from the kind of thinking and imagination involved in basic analog research (where scientists study locations on Earth because they approximate the conditions of sites on other planets). How is it that you found planetary scientists are “making Earth alien” as you say, and achieving resonance with such distant places like Mars, and planets around other stars?

Lisa Messeri: The inspiration for this paper came from encounters with planetary scientists when I could just feel their desire to connect with worlds that are beyond human experience. This desire to connect with the inaccessible is not unusual in scientific work (as you point out), but planetary science provides us with a unique edge case because Earth is of course also a planet. Whereas Mars and exoplanets are impossibly far away, planetary scientists have long recognized that Earth is an interesting object to think with when pondering what other worlds are like. As Apollo astronauts prepared to go to the moon, they underwent geology training in the American West so that they would be prepared for what they might encounter. The desert and canyon landscapes of Arizona or Utah continue to invite feelings of the extraterrestrial. In the article, I discuss my own experience of going to the Mars Desert Research Station (MDRS) in Utah where, along with a group of NASA scientists, I spent two weeks engaged in an imaginative exercise of what an early expedition to Mars might be like. The uninhabited stretch of desert surrounding the MDRS habitat had sparse vegetation and a red tinted soil. One might easily imagine it as “Mars-like.” And yet, during most of our time at MDRS my crew, as we called ourselves, was very aware that we remained on Earth. Confusing our planet for another was done with a joking tone, maintaining the distance between Earth and Mars. Except for one moment. We were testing soil at the base of a butte one afternoon and as we were preparing to leave the site, the scientists I was with transformed in an instant from diligent, dispassionate workers to excited explorers. They became so excited because here, in the Utah desert, they discovered a rock formation known to exist on Mars. They had smiles on their faces, holding the formations and discussing them excitedly. As I was unaware of the connection, I observed with confusion the scene playing out in front of me. When the excitement died down, one scientist explained to me the connection between here and Mars. In those moments of flurry and discovery, what I describe as resonance, Earth had been made alien and these scientists were able to walk on Mars.

MOR: I was especially struck by your descriptions of resonance in planetary science as not only about a relationship between near and far objects but also based on the “excitement of transcendence” and “finding new harmonies.” This idea feels both scientific and also supernatural and in that way reminds me of quantum entanglement, what Einstein dismissively called “spooky action at a distance,” where particles separated by great distance continue to act on each other. What’s happening through these transcendent connections with far off places?

LM: Yes! What a great connection. We anthropologists of science love drawing attention to the rather unscientific practices that matter deeply for knowledge production. These are not practices that make this knowledge any less authoritative or trustworthy, but rather show that science is a human endeavor. Proving quantum entanglement required physicists to think beyond common sense and allow for the possibility not of similarity between two particles, but of sameness. There is an uncanniness to sameness, and the question you raise asks us to ponder this uncanniness and its meaning. Entanglement’s supernatural/transcendent/uncanny connections are resilient – once this sameness is established it is hard to be undone. Resonant connections, however, are fleeting. Sameness quickly slips back to similarity. But in that moment of resonance, for example when the scientist in the Utah desert suddenly sees Mars, the question arises: does knowing Earth become the same as knowing Mars? Does distance collapse? In other words, what is the power of sameness as a way to know, even experience, somewhere else?

MOR: So, in contrast to the resonance of different places, this idea of sameness in entanglement could also be thought of as wholeness. It’s not only that separated particles are continuing to act on one another, but that they’re continuing to be part of an original unity. This makes me wonder if you think some of the appeal for scientists in achieving resonance may also come from the way it almost works like sameness, by linking seemingly distant and different places to an original unity. Specifically, I’m thinking of the idea of a scientific universe in which everything has a shared origin which is all explainable using scientific theories. It also reminds me of theories about the origin of life on Earth that invoke a transfer from ancient life on Mars, for example, or the idea that ancient fossils on Mars could help us understand the emergence or origins of life on Earth. In my research I’ve been looking at how the objects of interstellar exploration and beyond (from distant galaxies to extraterrestrial intelligence) become intimate through science, imagination, and even science fiction. So, thinking about this through your concept of resonance, a planet circling a distant star may seem to be, metaphorically, “in another universe” to some people but maybe resonance works for scientists as a reminder that it’s still this universe, the same universe. I’m not sure whether “reminder” is the right word here, because you also write that it’s part of a future professional aspiration (of actually going there someday) which is being brought into the present.

LM: When the first exoplanets were discovered, they were nothing like our solar system. In the 1990s, the few known exoplanets were large gas giants circling their host star closer than Mercury orbits our sun. This upended scientific theories of how planetary systems formed and raised the question of whether our solar system was unique. Now, with thousands of exoplanets detected, scientists believe that there are indeed solar systems like ours (as well as those more alien). There is a trajectory here of being confronted with the alien and moving back toward the (comfort of the) familiar. I think you are right that this is a “reminder” or at least a return to a desire to find ourselves/ourplanets elsewhere in the universe. As cosmologies, the big bang and the notion that we are all star stuff push thinking toward a sense of unity. However, the excitement of experiencing Earth as another planet comes from knowing that moments of sameness are possible but not permanent. This punctures the idea of unity, and I wonder if your interstellar objects offer a similar puncturing.

MOR: I’m struck by the way these tensions between sameness and difference you find in planetary science, which are about our ability to know something across great distance, also speak to ongoing debates within anthropology about ways to know something about people across difference. Anthropologists continue to debate whether there are more cultural similarities among humans than differences, or whether people who seem to have different worldviews from others may truly be living in radically different worlds. From the perspective of the planetary scale, as Carl Sagan said, we may seem “scarcely distinguishable” from the other inhabitants of Earth. And yet, sometimes it feels as though we struggle to know or understand what’s going on in other people’s worlds. You write that resonance is not only a way to overcome physical distance, but also a way for social scientists to overcome another kind of distance, social distance, and a tool for approaching the challenge of understanding what the people we study are up to and what it means. I’m reminded of anthropologist Martin Holbraad, who writes about responding to people’s seemingly outlandish claims not by trying to explain them away, but by expanding our repertoire of concepts we use to describe difference, an approach that he says “gets us out of the absurd position of thinking that what makes ethnographic subjects most interesting is that they get stuff wrong.” Does resonance also help you as a scientist who studies other scientists? How does it help make sense out of what you describe as a seemingly “outlandish claim” of “being on Mars”?

LM: I absolutely rely on the strategy of identifying similarities between myself and those I study to both make them feel comfortable with my presence and to reflect on similarities in our practices. I’m often very quick to let my interlocutors know that I have a bachelor’s degree in aerospace engineering so that I go from being seen as “one of them” to “one of us.” This is a step of establishing similarity, and creates the possibility for resonance without guaranteeing it. Additionally, by framing the work of Mars simulation as “fieldwork,” I render a mystifying (to me) practice in an interpretable context related to my own research method. But, it’s that tension between similarity and difference that I think is really crucial in studies of sameness and resonance. Early readers of this article pushed me to define resonance as specifically as possible and this article argues that it is a moment of sameness that abolishes distance and difference. But for resonance to have the excitement I claim it does requires difference to have been previously present. So perhaps what this suggests is that similarity and difference are not static but dynamic. This challenges us to creatively track such changes and to consider the implications of these changes for both those we study and our analyses.

Michael P. Oman-Reagan is a Vanier Scholar in the Department of Anthropology at Memorial University of Newfoundland. His research is supported by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada.

Lisa Messeri is an Assistant Professor of Science, Technology, and Society at the University of Virginia. Her book “Placing Outer Space: An Earthly Ethnography of Other Worlds” based on her fieldwork with planetary scientists was published in 2016 by Duke University Press. You can follow her on Twitter at @lmesseri.

Wonderful piece! Great work as always Michael and Lisa.

Superb discussion. Thank you for sharing this.