By Tiatoshi Jamir

I was born on a land declared an ‘Excluded Area’: a previously colonized region. A geographic landmass formerly carved out of Assam: lodged between Myanmar to its east, Manipur to its south, bounded by the plains of Assam to the west and snow clad mountains of the sub-Himalayan region of Arunachal Pradesh to the north. Now tagged for tourism purposes as ‘The Land of Festivals,’ it is the very same homeland where Naga ancestors were once branded ‘wild’, ‘savage’, ‘primitive’ ‘uncivilized’ ‘barbaric’ and ‘head hunters’ by the colonial powers. This colonial stereotype of the Nagas continues and is reiterated in the neighboring states and Mainland India. A case in point is Manpreet Singh’s article The Soul Hunters of Central Asia (2006) published in Christianity Today that describes the Naga homeland as “once notorious worldwide for its savagery”, now “the most Baptist state in the world.”

Abraham Lotha (2007), a noted Naga anthropologist, maintains that British colonialism in the Naga Hills is a story of double domination: political and scientific. This is evident in the production of mass ethnographic materials, topographical survey reports and monographs that aided colonial administration in their attempt to control the colonized. The museum collections that began in the early 19th century conveyed a certain awareness of the Nagas to the rest of India and the West by putting them in ethnographic museums, on geographical/ethnographic maps, and in weighty books (Schäffler 2006b: 292, cited in Stockhausen 2008: 64). For a visiting European, the Naga Hills were a ‘museum-piece’ and the objects (both archaeological and ethnographic) were collected from the colonies and displayed in the West as a way to authenticate the primitive stages of human development. The region was perceived as a cultural backwater. This part of India, that was once a portion of the Hill District of Assam, later came to be recognized, after much political unrest, as the 16th State of India called ‘Nagaland’ on 1st of December, 1963.

Although I was born in a small suburban town in eastern Nagaland, I grew up experiencing a typical Naga life. As a teen, I learnt how to swing a dao (a local iron machete), how to sharpen the blade most effectively, and how to shoot a target with a gun. I slashed and burnt thick forest for cultivation, learnt the traditional skill of fire-making, carried loads of paddy on my shoulder after a bumper harvest, built traditional houses with my peers, laid fishing traps and other traditional means of fishing, read animal tracks and hunted, roamed the deep forests foraging and gathering for wild berries, fruits, and edible vegetables. Not only were these moments a part of my leisure time but I took great pride in what I learned for it was a part of my heritage. Inculcating such traditional values was not only key to one’s survival but was also considered gender assigned roles for a Naga man. Little did I realize that it was these early experiences that drew me close to anthropology, a discipline that would allow me to study about myself and our Naga culture.

My fascination for archaeology developed while I was a graduate student of Anthropology in Kohima Science College. On one occasion, one of my professors, now a senior anthropologist, shared his experience as a member of the excavation team (1992) to Chungliyimti. At that time, we were told that Chungliyimti was a ‘Neolithic’ site, with great potential for understanding the beginnings of agriculture in the region. My involvement in archaeology developed, coupled with a strong yearning to visit this ancestral village that held historical ties with the clan with which I identified. I realized then that archaeology could contribute to the rich cultural heritage of our Naga pre-colonial past; a subject that was different from what I studied in the Political and Economic History classes in my high school. Archaeology provided me not only a career, but also an understanding of a deeper sense of identity as a Naga.

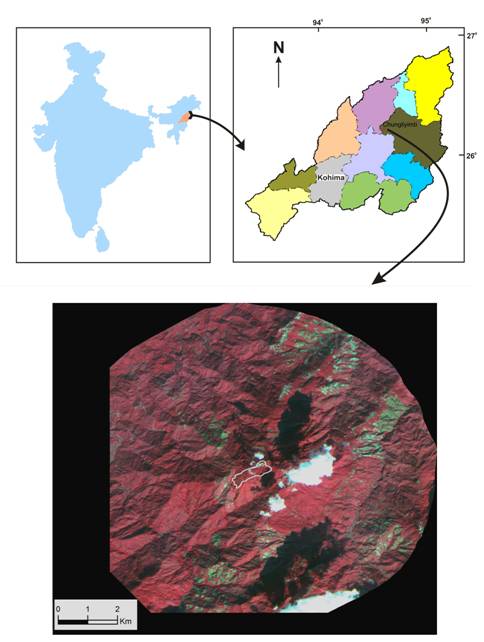

According to legend, our great ancestor Yimsenpirong of the Jamir clan was known to have spotted the first fresh water during early Chungliyimti times. Oral tradition recounts Chungliyimti as the once ancestral village of the Aos, few sections of the Changs, Phoms and Sangtams. These were communities that were labeled as ‘tribes’ in colonial accounts. An Ao origin myth also informs of the emergence of progenitors of the Aos from six stones or Longtrok (Long-stone; trok-six) after which they founded Chungliyimti. The site remained deserted for few centuries until it was re-occupied by some members from Chare and Tonger village (Northern Sangtam Naga) and Longsa village (Ao Naga). Today, the residents of Chungliyimti who partly occupy the ancient site are the descent communities of these later occupants (Figures 1 & 2) and continue to trace their historical link to this ancestral site.

Figure 1: Location map of Chungliyimti

Figure 2: A partial view of Chungliyimti presently occupied

Because of the special provision laid out in Article 371 (A) of the Indian Constitution, traditional land rights and ownership are still closely linked to the local communities. Hence, no Act of Parliament may apply directly to the State of Nagaland unless such Acts are passed in the Legislative Assembly of Nagaland. It is here that the host of legislation of the ASI remains to come into effect in Nagaland. Realizing this situation, my first visit to the site on October 2006 was mainly to acquire permission from the village authorities. Besides academic concerns, to me, this initial journey to Chungliyimti and Longtrok was considered a pilgrimage to the land of my ancestors.

This visit helped me reformulate methodologies that would best work for this research. Guided by previous works of Vikuosa Nienu (1974) and T.C.Sharma, I embarked on investigating this site further, fundamentally for few reasons: i) the lack of stratigraphic and historical context of the site and other site details ii) adopt alternative methodologies involving local community participation in archaeological research programs, iii) the historical ties that my clan shares with this particular site.

Preliminary excavations began in January 2007 with a research grant from the University Grants Commission, New Delhi. Further excavation continued in subsequent years with the involvement of the Anthropological Society of Nagaland and the Directorate of Art & Culture, Government of Nagaland. Pottery bearing carved paddle and cord-mark designs, wheel made kaolin potteries, a few ground stone tools, iron tools, carnelian and glass beads, spindle whorls etc. were the main materials retrieved. Charred remains of both wild (Oryza sp (cf. nivara); Oryza sp. (cf. rufipogon) and cultivated rice (Oryza sativa), and millet (Setaria sp.) native to the region were reported together with introduced cereals such as wheat (Triticum aestivum) and barley (Hordeum vulgare). Eight radiometric dates obtained assigned the site within cal. AD 980-1647 AD (see Pokharia et al. 2013; Jamir et al. 2014).

Community engagement and archaeology practice

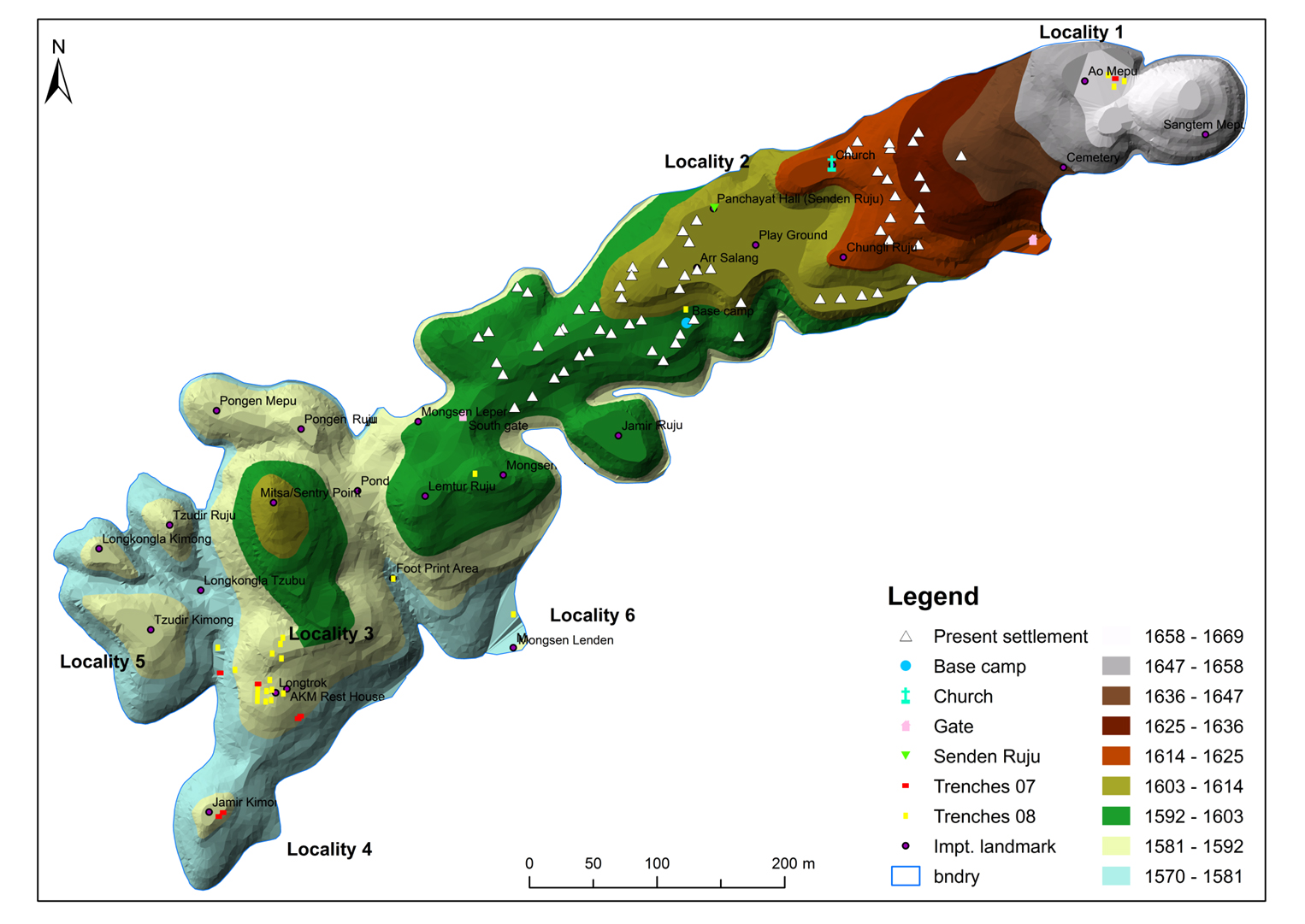

My effort to undertake a community-based archaeology at Chungliyimti stemmed from our past experiences with local communities at few Naga ancestral sites. With the aim of incorporating a more community-inclusive research and ascertain the level of mutual trust, several meetings were called with members of the village council to discuss ideas of the research program. With previous years of the site excavation, the community by now had removed all doubts that we were simply antique collectors, a remnant of the colonial past known in the region. Transparency of process increased the levels of trust among us, as did a collective social memory we shared with this ancestral site. The significance of the research and how the work aims to contribute to understanding the pre-colonial history of the region, corroborating both the ethno-historical accounts of the site and archaeology, the adaptive behavioral pattern within a sub-tropical monsoon environment were some of the key issues highlighted by the team. Community concerns such as measures to protect the excavated area and develop the site for tourism were other active engagements of the meeting. The mutual trust and respect further aided conversations on the myths of origin underlying Longtrok or ‘six-stones’ found standing at Chungliyimti. In trying to encourage multivocality and plurality, we were able to gain multiple perspectives of the past. To a large extent, the origin myth of Longtrok has been a subject of much debate to local scholars, centering on the politics of ‘who owns the past’? While the Ao Chongli ascribes the six stones to the three male patriarch of the Pongen, Longkumer and Jamir clan and their three sisters, the Ao Mongsen identifies the standing stones to six male ancestors (see Aier and Jamir 2009). Historical narratives linking the origin of the clan is also shared by the resident of Chungliyimti who too ascribes the monuments in commemoration of six major clans. What is interesting in the Northern Sangtam oral narrative is the description of the six clans which appears to revolve around the story of a ‘stone’. Few other important sites within 2-3 km radius of Chungliyimti were identified with the help of the community (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Identifying the locality where Yimsenpirong of the Jamir clan, led by a bulbul bird first spotted fresh water

Residents were also forthcoming to share details on their knowledge of edible wild plants, medicinal plants and their frequent hunting grounds which contributed significantly whilst mapping site catchment resources. Because the community had a better understanding of the site’s landscape gained from their seasonal cultivation around the site, their accounts aided in identifying artifact-rich clusters, and the extent of site disturbances in cultivated plots (Figure 4).

Figure 4: An ArcGIS generated Digital Elevation Model of Chungliyimti showing the prominent localities identified as a result of community engagement

Given the time constraints at our disposal, these important details of the site enabled us to effectively plan our digs. Another important initiative is the community’s engagement in experimental archaeology. A traditional hut was set up in one of the trenches following a good understanding of the house plans exposed during excavation (Figure 5) (see Jamir 2014).

Figure 5: View of a traditional hut within one of the excavated trenches, built with the effort of the community following the plan of one of the excavated residential site.

Often after a conference paper or publication, my Mainland colleagues ask how I dub the site. Perhaps to them, the site must conform to mainstream archaeological trajectories–Neolithic, a Bronze Age, Chalcolithic or an Iron Age site or it is utterly nonsense archaeology! In spite of K. Paddayya’s call for Multiple Approaches to the Study of India’s Early Past (2014), it seems that we continue to be obsessed with Universal tags and labels. Besides the problematic of such categories, I am doubtful whether coining Anglophone terms like ‘Neolithic’, ‘Bronze Age’ and ‘Iron Age’ is even applicable to the Naga Hills and its pre-colonial history. I have come to realize that mainstream archaeology is ethnocentric, particular and colonizing in a manner that prevents connecting with an Indigenous present. By creating period boundaries and assuming that Indigenous pasts look like normative presents (see Wobst 2005: 17-24). Rather, I would recommend overriding the technological trajectory cocoon and instead, identify these sites as ‘ancestral sites’ where our clan histories and stories of migrations are still relevant in the lives of descent communities today. Such a label deems fit considering the present descent groups (including my clan history) who relate our own ancestral past to this site, a site where Indigenous views such as the oral tradition, the meanings assigned to particular features of the landscape (toponym), and folk songs have played significant role in the interpretation of Chungliyimti. Like any other research, the present one is not without its problems. However, as pointed out by Shoocongdej (2009; also see Rizvi 2006, 2008; Selvakumar 2006), there is no single way of practicing community archaeology and is bound to inherently differ depending on the historical and cultural context of the community under study. It is, therefore, the collaborative practice of involving indigenous and other worldviews into archaeology that signals a positive process of decolonization of the discipline (Atalay 2007).

References

Aier, A. and T. Jamir. 2009. Re-interpreting the Myth of Longterok, Indian Folklife 33 (July): 5-9.

Atalay, S. 2007. Global Application of Indigenous Archaeology: Community Based Participatory Research in Turkey, Archaeologies: Journal of World Archaeological Congress 3 (3): 249-270. DOI: 10.1007/s11759-007-9026-8.

Jamir, T. 2014. Ancestral Sites, Local Communities and Archaeology in Nagaland: A Community Archaeology Approach at Chungliyimti, in 50 Years After Daojali-Hading: Emerging perspectives in the Archaeology of Northeast India (Essays in Honour of T. C. Sharma) (Tiatoshi Jamir and Manjil Hazarika Eds.), pp. 473-487. New Delhi: Research India Press.

Jamir, T. et al. 2014. Archaeology of Naga Ancestral Sites: Recent Archaeological Investigations at Chungliyimti and Adjoining sites (Vol-1). Department of Art and Culture, Government of Nagaland. Dimapur: Heritage Publishing House.

Lotha, A. 2007. History of Naga Anthropology (1832-1947). Dimapur: Chumpo Museum.

Nienu, V.1974. Recent Prehistoric Discoveries in Nagaland-a survey, Highlanders II (1): 5-7.

Paddayya, K. 2014. Multiple Approaches to the Study of India’s Early Past. New Delhi: Aryan Books International.

Pokharia, A. et al. 2013. Late First millennium BC to Second Millennium A.D. Agriculture in Nagaland: A Reconstruction based on Archaeobotanical Evidence, Current Science 104 (10), 25 May:1341-1353.

Rizvi,U.Z. 2006. Accounting for Multiple Desires: Decolonizing Methodologies, Archaeology and the Public Interest, India Review 5(3-4):394-416. DOI: 10.1080/ 1473 64 80600939223.

Rizvi, U.Z.2008. Decolonizing Methodologies as Strategies of Practice: Operationalizing the Postcolonial Critique in the Archaeology of Rajasthan, in Archaeology and the postcolonial critique (Mathew Liebmann and Uzma Z. Rizvi Eds.), pp.109-127.UK: Altamira Press.

Selvakumar, V. 2006. Public Archaeology in India: Perspectives from Kerala, India Review 5 (3-4): 417-446. DOI: 10.1080/14736480600939256.

Shoocongdej, R. 2009. Public archaeology in Thailand, New Perspectives in Global Public Archaeology (K.Okamura and A.Matsuda Eds.),pp.95-111.New York: Springer.DOI: 10.1007/978-1-4614-0341-8_8.

Singh, M. 2006. The soul hunters of Central Asia, Christianity Today [Online] available at http://www.christianitytoday.com/ct/2006/february/38.51.html.

Stockhausen, A. 2008. Creating Naga: Identity between Colonial Construction, Political Calculation, and Religious Instrumentalisation, in Naga Identities: Changing Local Cultures in the North East of India (Michael Oppitz et al. Eds.), pp. 57-79. Ethnographic Museum of Zürich University: Snoeck Publishers.

Wobst, M.H. 2005. Power to the (indigenous) past and present! Or: The theory and method behind archaeological theory and method, in Indigenous Archaeologies: Decolonizing Theory and Practice (Claire Smith and H. Martin Wobst Eds.), pp. 17-32. London and New York: Routledge.

Biography

Tiatoshi Jamir is an Associate Professor in the Department of History and Archaeology, Nagaland University, Kohima Campus, Nagaland, India, where he teaches prehistory and ethnoarchaeology. His broad professional interest also extends to the field of ethnomusicology and is front man of the folk-jazz band Blue Print. He is lead editor and author of the books 50 Years After Daojali-Hading: Emerging Perspectives in the Archaeology of Northeast India and Archaeology of Naga Ancestral Sites (Vol-1 & 2). He currently directs a research program on the Archaeology of Mimi Caves on the Naga Ophiolite belt adjoining Myanmar in collaboration with the Department of Art and Culture, Government of Nagaland. He is Vice-Chairman of the Anthropological Society of Nagaland, and is a member of the Indian Society for Prehistoric and Quaternary Studies, Indian Archaeological Society, and Society of South Asian Archaeology. Follow Tiatoshi on facebook and academia.edu.

For more of Tiatoshi’s scholarship, please see his Academia Account: https://nagauniv.academia.edu/TiatoshiJamir