By: Elisa (EJ) Sobo

The US cannabis landscape is shifting quickly, and so is the way we talk about the plant and its uses. The push to end its prohibition has entailed a proliferation of stakeholder groups, each with its own labeling preferences. Interviews with Southern Californian parents using marijuana medically for children with intractable epilepsy (pharmaceutically uncontrolled seizures) taught me that what’s in a name matters—a lot. How it matters differs depending on who is talking, and what he or he seeks to accomplish when it comes to this plant and its products.

Cannabis—marijuana—has many medical applications, including for epilepsy. Parent interest in this rose sharply when CNN profiled its success with a child in Denver. However, little scientific research has been done with the plant (its legal classification makes that tricky), so doctors generally will not assist parents proactively in regard to its use. Word of mouth, online resources, and purveyor promises are often all that parents have to go by as they work out dosage and other aspects of their child’s cannabis regimen. My research explores how they manage this, which has implications for our understanding of how regular citizens contribute to biomedicine’s knowledge base and therapeutic tool kit. Findings also may be used to help improve service provision for these vulnerable families.

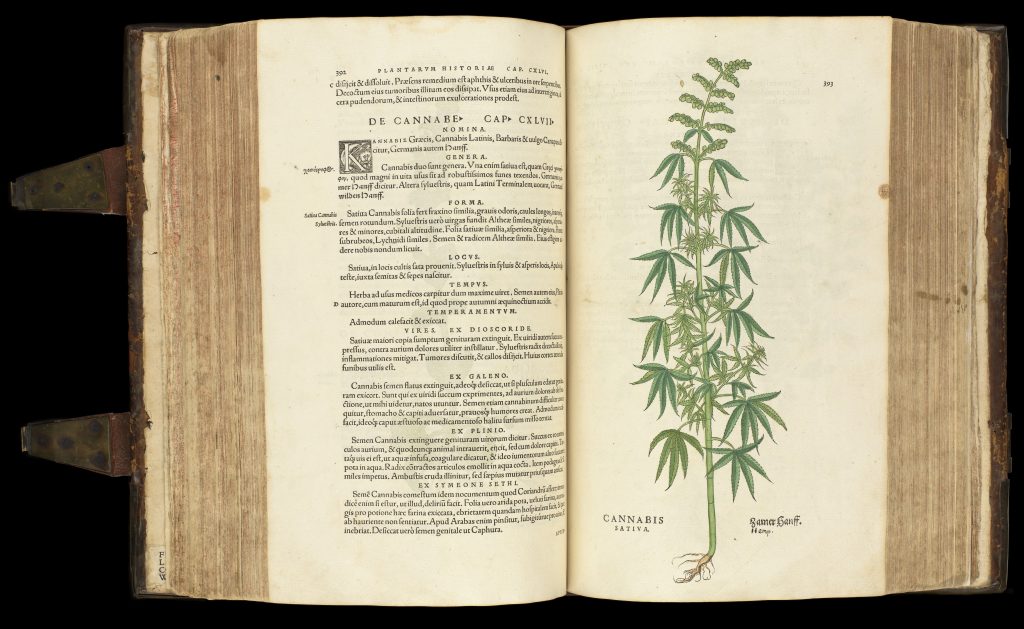

In pressing their case for access, most parents prefer the plant’s scientific name over lay terms. Cannabis, technically the genus label, sometimes is accompanied by species information too (i.e., Cannabis sativa or Cannabis indica). Many refer just to the key phytochemical CBD (cannabidiol); some talk also of other components of the plant (e.g., CBN, THC, THCA, and various terpenes).

Some parents advocate a whole plant approach, seeking to leverage what experts call the ‘entourage effect,’ in which plant chemicals act synergistically with one another. Such parents generally also prefer local or home grown raw materials and homemade or artisanal products. They tend to call the plant by its popular names (e.g., marijuana, pot). CBD, when referenced, is spoken of as part of a whole.

Yet most parents prefer scientific, medicalized rhetoric even when more generic terms would do. Cannabis, for them, is always capitalized and italicized. CBD and so forth are spoken of as isolates or molecules. In this discourse parents praise the regularity and predictability of big pharma’s highly systematized but reductionist production regimes.

Language is power

Through medicalized speech choices, parents proclaim themselves as knowledgeable insiders who belong in conversation with medical experts. It is the case that their children are often medically unique; parents often do know more about their children’s conditions than their doctors; they certainly know more about pot: they have to. But to get doctors to acknowledge this, parents cannot speak in lay terms. By calling pot Cannabis, using chemical names, and so on, parents assert their right to participate in discussions with authorized experts as more than ‘just’ parents.

They also assert their difference from casual or recreational users by refusing terms (e.g., weed, pot) that others associate with, as one mom put it, Cheech and Chong. Not all parents frowned on recreational use automatically. Some saw the medication–recreation binary as clearly prejudicial. But the primary aim of getting children high was not something with which any parent wished to be associated.

It is no coincidence that parents initially prefer low or no-THC formulations; they also prefer cannabis oils, dropped under the tongue or into a feeding tube, rather than inhalation or having the actual herb in the house. Their children’s medicine looks how medicines are ‘supposed’ to look; and it is treated accordingly.

Of course, recreational users also deploy medical language—at least in states where the only legal way to purchase cannabis is with a doctor’s referral. These are notoriously easy to get and people continue the charade in ‘dispensaries,’ which are used not so much by sick individuals (who favor home delivery) as by a young and healthful crowd that talks about ‘medicating’ rather than ‘partying’ or ‘getting high’ (terms that I am told are used where doing so is legal)..

The recreational market has invented new terms too. For instance, ‘dispensary’ sales clerks are ‘budtenders.’ In so obviously equating pot to alcohol, this term’s use may be read as a raspberry blown to law enforcers; or it may be an optimistic and celebratory disavowal of the need for subterfuge given changes in legalization that appear to be on the horizon. It certainly acknowledges the ludic side of leisure use.

It is not that parents are overly sober: laughter and ironic humor infused many an interview. But having a sick child is no game. Having to call one’s provider a ‘budtender’ is degrading to medical customers who deeply desire authentic, recognized legitimacy—not a nod and a wink. This need is one reason some parents were willing to wait up to one year to be seen by one of the region’s few well-reputed cannabis-approving physicians instead of using a fly-by-night referral mill. The need for real medical advice, and concern about cannabis’s interaction with their children’s other medications, also came into play.

Use of cannabis slang also was seen by some as degrading, implying likewise that one’s turn to the drug or drugs that this plant produces is neither medically indicated nor necessary. Take the term ‘weed,’ which suggests that cannabis should not be considered a legitimate cultivar. Silly strain names such as AC/DC and Sour Tsunami connote a kind of playfulness that may be seen as inappropriate when it comes to serious illness. Some terms even are—or at least were, originally—xenophobic or racist. For instance, the word ‘Marijuana’ was promoted purposefully by US anti-drug interests in the 1930s specifically because it sounded Spanish and thus provoked or leveraged, in some Euro-Americans anyhow, anti-Mexican or Hispanic sentiment. Associations of the older argot with criminality also are rife. Indeed, based mostly on this history, some activists have chastised the media for using lay terms and puns (e.g., “high time”) in cannabis-related headlines and reporting.

Using the language of science instead highlights the legitimate medical potential of the cannabis plant. It helps parents gain credibility with (other) experts by giving a ring of legitimacy to their claims. In the short term this may help speed access to pharmaceutically manufactured cannabis medicines by increasing the publicly perceived legitimacy of this need. As an added plus, pharmaceutical manufacturing processes help in the regulation of dosing and they insure consistency across batches, and purity, reducing the necessity that parents send what they buy out for testing to find out what it really contains. For such reasons, using scientific terms and referencing chemicals makes good sense.

Must we choose?

Yet, history suggests that overly-insistent medicalization will have costs. It may support a transfer of all authority over cannabis to the mainstream healthcare system, disenfranchising parents—whose empiricism and perseverance helped open the healthcare industry’s eyes to the plant’s promise to start. Resulting dependence on corporations and expert systems could foreclose the option of growing and preparing treatments oneself despite the relative ease of doing so. Some parents fear loss of access to the entourage effect because isolated compounds like CBD are being favored over whole-plant products in pharmaceutical processes; price hikes also could occur. For reasons such as these some activists say that at least high CBD strains of cannabis (also known a hemp) and CBD-based medicines, which have no psychoactive component, should be left out of the debate; there is a bill making its way through congress right now (H.R.5226) that would reclassify these as non-drugs, making them as legal to possess or prepare as sauerkraut.

Whether or not that happens, whole-plant language reminds us that cannabis-based drugs come from a flowering herb. It also can help consumers retain some authority over their use of that herb for health and healing. Preserving consumer rights is particularly important in regard to conditions such as intractable epilepsy, which by definition mainstream medicine cannot treat.

This is not to say that medicalized rhetoric is wrong and whole-plant language is right. Rather, we must preserve a context-sensitive combination of ways of talking about pot. In parallel with the entourage effect, each mode of expression, taken together, may well be more effective in fostering human health than a single discourse used in isolation.

Elisa (EJ) Sobo is a professor of anthropology at San Diego State University and President of the Society for Medical Anthropology. She is on the editorial boards of Anthropology & Medicine and Medical Anthropology and she is the Book Reviews Editor for Medical Anthropology Quarterly. Dr. Sobo has written numerous peer-reviewed journal articles as well having authored, co-authored, and co-edited twelve books, the most recent of which are: Dynamics of Human Biocultural Diversity: A Unified Approach (2012), The Cultural Context of Health, Illness, and Medicine (2010), and Culture and Meaning in Health Services Research (2009). Her current research includes not only parent use of Cannabis for children with intractable epilepsy or seizures but also cultural models of child development in Waldorf or Steiner education, and parental thinking on pediatric vaccinations and herd immunity. Interviewers for the Cannabis project include MarkJason Cabudol, Tiyana Dorsey, and Gabriella Kueber.