Weber’s metaphor of the iron cage is one of the most famous in all of sociology. It’s certainly stuck with me: I keep a bookmark in my copy of The Protestant Ethic (Talcott Parsons’ translation) at page 181 so I can always turn to the Iron Cage when I need it. Cos, like, you never know when you need to comment on the relationship between capitalism and the pervasiveness of rationalism.

Let’s pop in for a refresher.

It’s 1905 and Weber’s project is to undermine materialistic explanations for economic change by arguing that Protestant asceticism (self-restraint and the denial of pleasures) and the notion of having a calling (showing devotion to God by attending to worldly matters rather than seeking transcendence) laid the foundations for “modern rational capitalism.”

The Puritan wanted to work in a calling; we are forced to do so. For when asceticism was carried out of monastic cells into everyday life, and began to dominate worldly morality, it did its part in building the tremendous cosmos of the modern economic order. This order is now bound to the technical and economic conditions of machine production which to-day determine the lives of all the individuals who are born into this mechanism, not only those directly concerned with economic acquisition, with irresitible force. Perhaps it will so determine them until the last ton of fossilized coal is burnt. In Baxter’s view the care for external goods should only lie on the shoulders of the “saint like a light cloak, which can be thrown aside at any moment.” But fate decreed that the cloak should become an iron cage.

Since asceticism undertook to remodel the world and to work out its ideals in the world, material goods have gained an increasing and finally an inexorable power over the lives of men as at no previous period in history. To-day the spirit of religious asceticism – whether finally, who knows? – has escaped from the cage. But victorious capitalism, since it rests on mechanical foundations, needs its support no longer. The rosy blush of its laughing heir, the Enlightenment, seems also to be irretrievably fading, and the idea of duty in one’s calling prowls about in our lives like the ghost of dead religious beliefs.

Not ten years after The Protestant Ethic was published, Gregor Samsa awoke to find his soft flesh transformed into the hard carapace of a beetle (see Peter Baehr’s “The Iron Cage and the Shell as Hard as Steel”). Why does rationality behave so irrationally? It is strange when capitalism, which in the contemporary scene so values flexibility and mobility, invents constraints for itself that inhibit the very qualities it thrives on. It can also be more than a little bit funny, if you don’t mind gallows humor.

In the passage above Weber is working with Ideals, but we don’t have to be so abstract to see little iron cages everywhere. In particular I have in mind ideologies setting in motion bureaucratic processes that result in the infrastructural facilities we all use in our everyday lives. Ideals not only hold us in place as if they were iron. Sometimes they really are iron. Or in the story I have to share, concrete.

From 2005-2006 my young family and I lived in a single-wide trailer outside the Qualla Boundary, an Indian reservation in far western North Carolina. I was working for the CHA, a formerly non-Indian organization now run by tribal members that operated two major tourist attractions: a living village and an outdoor theater. The CHA had been hemorrhaging cash for years and this precarious state is what allowed the tribe, its coffers flush with casino cash, to force out the old management. Eventually this would yield significant changes in how the tribe’s culture was represented to outsiders, but that’s another story.

Over decades of benign neglect the old management had thoroughly run the CHA into the ground and as catastrophe loomed there really wasn’t any evidence that they had tried to do anything significant to change course. There was just thirty years of steady decline as attendance dried up, then they ran out of money. Thirty years of each season selling fewer tickets than the year before. You’d think they’d pick up on the pattern! Our mission as the new stewards of the CHA was to shake things up, stage a new drama. And as we endeavored to do our best, along the way we’d discover relics the old regime had left behind.

This story from a CHA employee is about the dormitories backstage that housed the actors who performed in the drama:

The classic example of this is that they built… the four apartments that are just below the director’s A-frame. Whenever those were built, I’m not sure, probably the ’60s I’m thinking… When they put in the cinder block foundation and footers they put in the hot water heaters for the building and then built the building on top of it. And then built a door that was entirely too small to fit a hot water heater in or out of and there was no way from inside the apartments to replace those hot water heaters. And that just seems to sum up a whole lot of the way things were engineered and thought about and planned for. There was no attempt made to plan for replacing a hot water heater, which is a durable good but will always have to be replaced some time… At that point the drama may have only been in existence twenty years, but here we are thirty-seven years later and we have four hot water heaters underneath the house that we can’t remove because (laughs, slaps table) we’ve had to replace them.

The old leadership at CHA had no vision. They failed to anticipate anything. Not only did they fail to realize that thirty years of declining ticket sales would inevitably lead to a thirty-first year of declining sales, they were unable to foresee that a water heater with a twenty year life span will have to be replaced somewhere down the line. Their disposition towards the future, such as it appeared to us, was made manifest in infrastructural choices. And as capitalism heaped change upon more change that infrastructure kept them bound.

This allegory, which I’ve trotted out at numerous conference pub scenes, floated to the top of my memory once again as I’ve tried to make sense of the politics which pervade the museum where I am currently employed.

The museum facility is an odd amalgam of buildings dating from the early twentieth century to the present. The infrastructure presents us with three major problems: first the HVAC, security, and fire suppression in the older parts don’t do a good enough job of supporting our mission of preservation and conservation – its negligence to put rare books in a room with out precise climate control; second, the layout, which we lovingly refer to as the “double square doughnut” inhibits how staff and visitors alike move through space which in turn constrains how exhibits are designed; and third is the scarcity of room to grow, space is ever more at a premium and not just for collections and labs, but everything a large non-profit needs to run like human resources and payroll and conference rooms, etc.

And then, over and on top of this, consider how American culture (particularly how people consume, produce, and express relationships with information) has changed in the last century. Cultural institutions everywhere must contend with how to reach a contemporary public using an antique space that presumes outmoded forms of communication.

I work in the museum library which is currently housed in the special collections department of a nearby university. Now the university library is scheduled to expand and our sensitive materials must be moved to make way for the contractors, at least until the improved building reopens in 2017. We (the museum) don’t have much voice in this, we don’t even pay rent. In the meantime where will the library go? Even though the university’s expansion has been in the works for some time the museum administration is caught flat footed. There’s no plan. But there is plenty of politics as different executives compete to advance their agendas.

Save a few details such infrastructural dilemmas are no different than what many of you see in higher education. Facilities and operations act as material instantiations of political processes. Consequently those politics, ideologies, and cultures directly and indirectly shape the building which houses your office, the classrooms where you teach, and the databases you access online. As anthropologists we are in a unique position to illuminate how such abstract processes result in concrete outcomes (pun intended).

This is why I feel infrastructure studies are such an exciting development (for examples see Cultural Anthropology’s special coverage with The Infrastrucutre Toolbox). There’s power, the distribution of resources, environmental racism, all kinds of classic issues – really there’s a lot of different ways you can slice this pie. I’m particularly interested in how infrastructure plays a role in conflict over futures within institutions. As they grow, adapt, and change they may be predisposed to make certain choices because of the facilities in which they operate.

On the reservation working in the CHA was like running an obstacle course blindfolded. It was up to us to offer up new solutions to how the old regime had solved problems in the past, but without knowing what new problems those old solutions had created. When your problems are made of concrete and rebar they can be very persistent! I wonder if something similar is happening at the museum as we scramble to temporarily displace our entire library?

I wish more educational and cultural institutions had visionary leadership. Will ours bury the metaphorical water heaters behind doors too small to get them out? In the future will our problems, like the bullet in Chris Johnson’s shoulder (“apparently its still there”) be easier to ignore than to solve?

There must be ways to open the lock of the iron cage. Is infrastructure really so rigid?

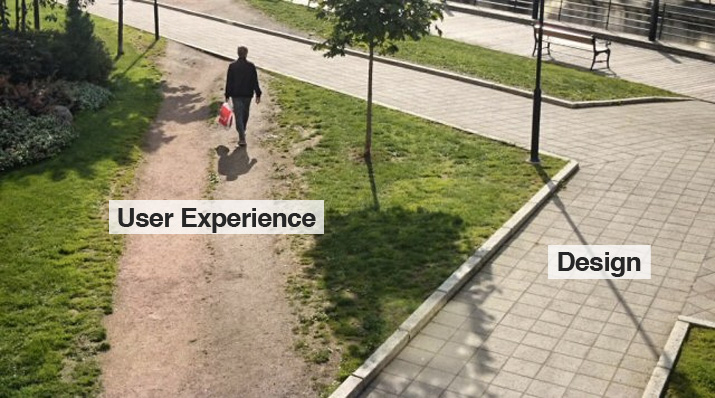

Certainly we can find a little relief through subversion. Like De Certeau’s pedestrian in the city we can all find our ways over, under, and around all manner of obstacles. Even if, like Chris Johnson’s bullet, we get used to it and forget that its there. We take shortcuts. We “know a guy” and make a phone call. We ignore rules and then feign ignorance. We gossip.

Mike Wesch had this online presence a few years back called Ed Parkour (I say “had” because I can’t find the link), which encouraged educators to view whatever obstacles we might encounter in the manner of parkour athletes. There is no parkour without infrastructure and there is no parkour that uses infrastructure in the way that it was intended.

The blog implies that “iron cage” was Weber’s chosen metaphor. It was not; it was an invention of his translator, Talcott Parsons, who in turn was drawing on the puritan John Bunyan’s , where a man in an iron cage is invoked. Weber’s phrase was “shell as hard as steel” (stahlhartes Gehause) and the connotations are quite different from “iron cage”. Iron is elemental; steel is modern. Cages trap people inside them; shells are an organic housing – and offer some protection. Weber’s point is that rational capitalism has produced a very different kind of being from that of previous times. For more detailed information on Weber’s imagery, see , Peter Baehr, History and Theory, Vol. 40, No. 2 (May, 2001), pp. 153-169. If anyone would like a pdf of this article, contact me at: pbaehr@LN.edu.hk

We should remember, too, the Calvinist doctrine of predestination, which divided humanity into the elect, those with callings and promised salvation, and the damned, doomed to Hell regardless.

I just want to highlight Peter’s comment since he is, like, one of the foremost scholars of Weber today. I believe the final chapters of his book “Founders, Classics, Canons” also discusses his choices in translating Weber in his version of PE&SoC.