A week before historic elections which swept Taiwan’s ruling Nationalist Party (KMT) out of power, KMT candidate Lin Yu-fang (林郁方) asked voters not vote for Freddy Lim (林昶佐, pictured above), asserting that he has “hair that is longer than a woman’s and is mentally abnormal.”1

Short hair for men in Taiwan was heavily regulated during the Martial Law era which ran from shortly after the KMT took over Taiwan after World War II until 1987.

During the martial law period in Taiwan, hair length for males was controlled and long hair could get you in trouble if you walked down the street sporting it. Naturally, control of hair length in the schools was an important component of shaping the students, and disciplining them to accept authoritarian control.

It was only in 2005 that schools finally eased restrictions on hair length for boys.

Barely a month before the Election the Taiwan Police Union had issued a statement in support of a police officer who was fired for having long hair. The union supported the officer’s claim that their firing violated the Gender Equality in Employment Act. The officer said that “although he is biologically male, he does not identify with either gender and firing him for not meeting the male-specific grooming standard is discriminatory.”

Of course, such battles over long hair for men are not unique to Taiwan. When he was 17 David Bowie was interviewed for the BBC about the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Long-Haired Men:

Its possible that the whole thing was a publicity stunt for a young singer, but the musical Hair came out a few years later, reflecting the strong association of long hair with counterculture. Despite some surface similarities, however, the symbolism of long hair on men in Taiwan has to be understood in light of Taiwan’s unique post-war history. (One could perhaps look back even further – to the queue worn by men during the Qing dynasty – but I’m not sure how relevant that is for understanding the present situation.)

During the Martial Law era, the KMT (whose leadership was made up of recent migrants who had arrived in Taiwan from China after the end of the Civil War) sought to legitimate their rule over Taiwan by promoting Chinese nationalism, claiming that the government in Taipei was the true government of all of China. In promoting this nationalist vision the KMT kept Taiwan on war footing, with military advisors in the schools and mandatory military training for male students. As such, military style haircuts were part of maintaining strict military discipline.

We can perhaps also find the importance of maintaining short hair in Confucianism which was promoted by the government as a kind of state religion. The birthday of Confucius is still an important state holiday (also known as Teacher’s Day), during which the president attends ceremonies at the Confucius temple in Taipei. Confucian patriarchy served the KMT by treating the nation as a family unit and each institution within the nation as a synecdoche of the national family. This can still be seen in Taiwanese schools where students refer to classmates as younger or elder brothers and sisters. The state had a vested interest in preserving the national patriarchal family structure and thus sees gender-bending long hair as a threat.

After the lifting of Martial Law in 1987 much of this changed. The state shifted strategy, and many of these practices were no longer essential to the maintenance of legitimacy, which became grounded more in Taiwan’s vision of itself as a multicultural and tolerant democracy. At the same time, as a result of stagnant wages and a increased sense of precarity among Taiwan’s middle classes, there is still a faction of Taiwanese society nostalgic for the law and order of the Martial Law era. These generational differences came to a head in the Sunflower Student Movement two years ago, and Taiwanese campaign ads played up these differences in the run-up to the elections.2

The first, by the KMT, captures the sentiments of those who long for the rapid economic growth and strong Confucian values of the 1960s [Note: turn on CC for English subtitles]:

The second, by the Democratic Progressive Party (民主進步黨 DPP), tries to capture the spirit of the Sunflower Movement.

As the lead singer of Chthonic, “arguably the biggest death metal band in Asia,”3 Freddy embodied many of the generational tensions represented by these videos. Here he is with his stage makeup:

Importantly, Freddy did not run as a DPP candidate. Instead, he helped create the New Power Party (時代力量 NPP). The NPP calls itself a “third force” and aims to attract new political voices, such as those mobilized during the Sunflower Student movement, many of which have felt alienated from traditional party politics.

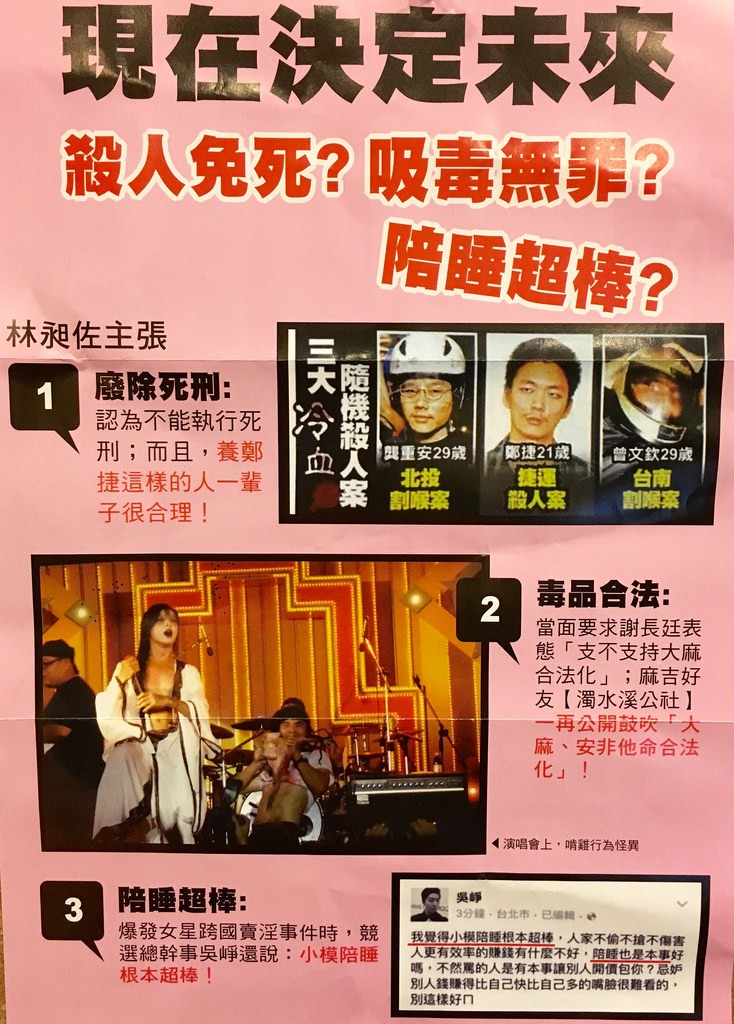

Because Freddy ran in the Taipei district where I live the following anti-Freddy flier was placed in my mailbox the week before the election:

It attempts to link Freddy to ending the death penalty and legalized drugs and prostitution. The evidence for Freddy’s support of these policies presented in the flier is rather tenuous, largely relying on statements from friends and known associates. Nonetheless, the moral panic associated with a long haired rock musician is risible, especially when compared with emerging norms in Northern Europe and parts of North America. But Freddy’s alt-culture identity was a central part of his appeal to younger voters and so it will be interesting to see how the NPP is able to hold on to its renegade status as it assumes its new role as junior member in Taiwan’s new ruling coalition.

- Although he later clarified that Lim’s long hair was not the reason he called him abnormal. ↩

- Thanks to Ben Goren for bringing these two videos to my attention. ↩

- It seems the proper term for this style of music is “black metal” not “death metal.” If you read French, you might want to look at this article about the black metal scene in Taiwan. ↩

It reminds me of long-hair phobia in the US in the 70’s. Non-typical appearance is perceived as a threat. Perhaps it is to the established mores of the day. In the US in loosened up society for progressive changes. Perhaps it is now beginning in Taiwan.

Two things: I’m not sure how relevant it is here, but school girls up to the end of high school also had to maintain short-cropped hair during the martial law era. It had to be cut at ear-lobe level–extremely unattractive. The other thing is, I’m not sure what you mean about the ‘importance of maintaining short hair in Confucianism.’ Cutting the hair (along with tattooing and body piercing), for both men and women, was a sin against the ancestors who had bestowed the individual’s body upon them. Both men and women wore their hair long until the Manchu’s imposed their style on their Chinese subjects. One of the main reasons that Chinese did not happily adopt the Manchu coif was that it involved shaving the hair on the front of the head, which was considered contrary to Confucian teaching.

Thanks Terry. When I discuss Confucianism here I should be clear that I’m talking about how it was promulgated by the patriarchal Taiwanese state, not making reference to any traditional texts. While I’m not ready to dismiss the idea that long hair on men is threatening because of the state’s investment in maintaining gender roles, the fact that girls also had to keep their hair short does imply that perhaps a general focus on authoritarianism and military preparedness was more important. More on girls hair regulations can be found in this Taipei Times article from 2005: http://www.taipeitimes.com/News/taiwan/archives/2005/08/22/2003268711

Japanese musician Kitaro was banned from playing in Singapore because of his long hair: https://singaporearmchaircritic.wordpress.com/2013/11/10/from-harrying-long-haired-men-to-embracing-casinos/

I suppose I’m not so convinced of how important Confucianism was vis a vis long hair. Clearly Confucianism, as an ideology, was fundamental in defining Chinese/Taiwanese patriarchy, but was there anything in Confucianism that made the patriarchy more anti-long hair? Certainly not in traditional terms. I haven’t personally seen it, but I’m sure that the image of Confucius in the Taipei Confucius temple has long hair. And my own father didn’t need a Confucian world view for him to feel that my long hair in the 1960s was a threat to his authority.

Terry, I think what happened in Taiwan and throughout East Asia was a sort of reversal: first, early male modernizers adopted short haircuts as a rejection of Confucian tradition and adoption of “Western” modernity (including its pseudo-science of gender). (In China this overlapped with Han nationalist rejection of the Manchu queue.) Later, modernizers in power began enforcing short haircuts for men, less a rejection of tradition and more as an enforcement of gender norms and, eventually and ironically, also to enforce some idea of national identity in opposition to decadence associated with Western counter-culture in the 1960s-1970s. In countries that had revived Confucianism in modernized forms as part of this national identity, short haircuts thus may have become ironically conflated with Confucian masculinity. (This seems to be the case in Taiwan, Singapore and South Korea. Not sure about elsewhere.) In countries that still officially rejected Confucianism (PRC, DPRK, Vietnam), short haircuts were framed as “socialist” in opposition to “Western bourgeois spiritual pollution” — until, in a double irony, the PRC revived Confucianism as part of the official ideology.

Another thing I’d like to point out, in addition to Terry’s point about Han opposition to the Manchu queue, is that the Confucian rule against cutting hair (身體髮膚,受之父母,不敢毀傷,孝之始也) was one of the points that Confucians in the Han Dynasty highlighted in opposition to the incursion of Buddhist monastic practices at the time.

He also got attacked for burning the ROC flag amongst other things http://translatingtaiwanlit.com/2015/12/23/smearing-political-rivals-in-taipei-freddie-lim-take-down-%e6%9e%97%e6%98%b6%e4%bd%90%e8%a2%ab%e6%9e%97%e9%83%81%e6%96%b9%e3%80%8c%e6%8a%ba%e9%bb%91%e3%80%8d%e4%ba%86/

The hair thing is particularly bizarre though

It would be interesting to see some anthropological perspectives on this case. I’d recommend that Kerim start with Leach’s classic Curl Prize essay “Magical Hair” from 1958, which argued for a space for symbols in an anthropological tradition that tended to focus on what Leach somewhat dismissively called “social structure.”