For the next installment of the anthropologies issue on climate change, we have a counterpoint essay from Lee Drummond. Drummond is a retired professor of social/cultural anthropology (McGill University). For the past twenty years he has been director of a very modestly staffed think tank, the Center for Peripheral Studies in Palm Springs, CA. As a “real” anthropologist he studied South American myth and Caribbean ethnicity. Later, reincarnated as a “reel” anthropologist he applied his work on myth to blockbuster American movies, treating them as myths of modern culture (see American Dreamtime). –R.A.

The principal “texts” for this little essay are a 2009 lecture, “Heretical Thoughts about Science and Society,” by Freeman Dyson, one of the smartest people on the planet, and an epic performance, “Saving the Planet,” by George Carlin, until his death in 2008 one of the funniest people on the planet. Dyson’s lecture may be found here.

It’s over an hour long, but watch the whole thing–it’s great. Carlin’s performance is on YouTube.

It will take only a few minutes of your day.

Before taking up a few specifics of these pieces, let me provide a background sketch of the phenomenon of global warming that has attracted so much attention over the past couple of decades.

The Big Picture: Greenhouse Earth and Icehouse Earth

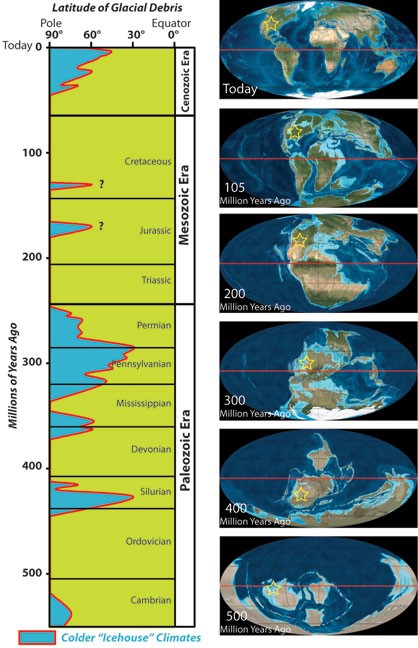

Environmentalists gravely concerned with rising CO2 levels in the atmosphere and rising temperatures in the oceans not uncommonly issue the dire warning that these are runaway processes, that Earth will continue to get cloudier and hotter until it becomes another Venus, where lead can melt on its surface. The entire history of the planet suggests that this is not the case. Earth’s climate has oscillated through periods of unusually hot conditions (Greenhouse Earth) and unusually cold conditions (Icehouse Earth), each period lasting tens or hundreds of millions of years.

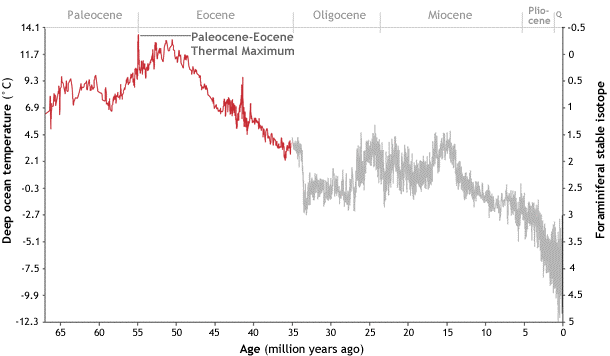

As it happens – though you wouldn’t know it from watching cable news – since the mid-Miocene, around 15 mya, the planet has been in its “Icehouse Earth” phase. Global temperatures have declined precipitously during that period, so that the recent climate is the coldest since the beginning of the Permian Period, around 280 mya (see graph below):

The last “Greenhouse Earth” occurred during the period 45-55 mya, marked by the Paleocene – Eocene Thermal Maximum. From that time global temperatures were on a more or less steady decline, culminating with the sharp drop from mid-Miocene to the present:

The Tropical Arctic

Another stretch of Earth history that scientists count among the planet’s warmest occurred about 55-56 million years ago. The episode is known as the Paleocene-Eocene Thermal Maximum (PETM).

Stretching from about 66-34 million years ago, the Paleocene and Eocene were the first geologic epochs following the end of the Mesozoic Era. (The Mesozoic—the age of dinosaurs—was itself an era punctuated by “hothouse” conditions.) Geologists and paleontologists think that during much of the Paleocene and early Eocene, the poles were free of ice caps, and palm trees and crocodiles lived above the Arctic Circle. The transition between the two epochs around 56 million years ago was marked by a rapid spike in global temperature.

During the PETM, the global mean temperature appears to have risen by as much as 5-8°C (9-14°F) to an average temperature as high as 73°F. (Again, today’s global average is shy of 60°F.) At roughly the same time, paleoclimate data like fossilized phytoplankton and ocean sediments record a massive release of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere, at least doubling or possibly even quadrupling the background concentrations.

The Pleistocene Roller Coaster

The long history of decreasing global temperatures is not constant. Particularly during the Pleistocene, from around 2.5 mya to 12 kya, the Earth’s climate fluctuated dramatically (reference the graph above). Some twenty glaciations occurred during that relatively brief period, with associated changes in the planet’s biota. Why the dramatic climatic changes? It’s complicated:

The causes of the Pleistocene cycle of glacial and interglacial episodes are still being debated. It appears that continental positions, oceanic circulation, solar-energy fluctuations, and Earth’s orbital cycles combined to generate these glacial conditions, so perhaps it is inappropriate to pinpoint any single cause. Some scientists have calculated that changes in the concentration of greenhouse gases were a partial reason for large (5-7° C) global temperature swings between the ice ages and interglacial periods.

Anthropologists (and most environmentalists) are not qualified to weigh in on that debate, but we anthropologists may make two observations on the basis of the known facts. First, primate evolution in Africa during the early to mid-Miocene (15 – 25 mya) was facilitated by the warm, wet conditions there. Plenty of tropical forests, plenty of room for adaptive radiation. Since we wouldn’t be around were it not for those long-ago events, we really should acknowledge the role “Hothouse Earth” played in our appearance on the planet (this lesson will be repeated). Second, as the cooling-down process continued and accelerated into and through the Pleistocene, primate species experienced a great deal of adaptive stress. Tropical forests receded, grasslands took their place, the forests returned in different forms, disappeared again. Genetic change alone could not keep pace with these rapid alterations in the basics of existence. So, enter Homo. The early hominid species possessed something new: the (now rather maligned) faculty of culture. Their novel social arrangements and tool use provided them the leg up that was needed to cope with a world that kept changing around them.

There is a lesson here for anthropologists as they consider – as anthropologists and not as partisans – the strident debate over global warming. Environmentalists – who have crafted an ism of an aspect of the physical world (might we expect gravityists to appear on stage at some future date?) – decry the changes they see happening around them. They want to reverse those changes (more electric cars, solar power, clean coal, etc.) and thus restore the planet to an earlier state. They want to go back. The insurmountable problem, though, is that there is no “back.” The past is a record of endless change, and the future is just such a record, yet to be written. For the past century or so human activity undoubtedly has been a factor contributing to global warming, but that activity must be added to the list of other contributing factors identified above (continental positions, oceanic circulation, solar-energy fluctuations, and Earth’s orbital cycles).

Here it is useful to consider Freeman Dyson’s opening caveat regarding the science behind global warming: science is primarily about experimentation, not prediction. In an experiment, the scientist attempts to contrive a situation whose outcome is as uncertain as possible, then do the experiment and observe the results. If the result is thoroughly predictable beforehand, then it is useless or at least uninteresting to conduct the experiment. And while science does generate predictions (the motion of the planets, the schedule of lunar eclipses, the acceleration of falling bodies), its impressive ability to generate new knowledge rests on experimentation. And Dyson, as one of the foremost contributors to quantum theory (whose Standard Model is the most rigorous scientific achievement in history), is deeply skeptical of the predictive value of existing models of the future climate. Earth’s climate is a classic example of a dynamic system; a host of variables interact in ways impossible to specify exactly, with the result that the outcome of those interactions is unpredictable, always something of a surprise. It’s what is now a cliché: that butterfly flapping its wings in China produces a drought in the American Midwest. Models of climate change are almost exclusively meteorological; they ignore astronomical variables noted above, some of which may produce dramatic consequences. For example:

Some scientists say we could be headed for another “Little Ice Age,” given how eerily calm the sun has been in recent years.

. . . The sun goes through cycles that last roughly 11 years, marked by the ebb and flow of sunspots on its surface. At peak sunspot activity, the so-called solar maximum, the sun sports lots of sunspots and is steadily unleashing solar flares and coronal mass ejections (CMEs). Since our current solar cycle, Number 24, kicked off in 2008, the number of sunspots observed has been half of what heliophysicists expected.

“I’ve never seen anything quite like this,” Dr. Richard Harrison, head of space physics at Rutherford Appleton Laboratory in England, told the BBC. “If you want to go back to see when the sun was this inactive in terms of the minimum we’ve just had and the peak that we have now, you’ve got to go back about 100 years.”

. . . But a relatively quiet sun could cause problems. Some scientists say that this period of weak solar activity may mirror what happened before the so-called Maunder Minimum of 1645 to 1715 — a period named after solar astronomers Annie and E. Walter Maunder, who studied sunspots and helped identify the sun’s strange activity in the latter part of the 17th Century. That time period saw only 30 sunspots (one one-thousandth of what would be expected) and coincided with a “Little Ice Age” in Europe, during which the Thames River and the Baltic Sea froze over.

Mike Lockwood, professor of space environment physics at the University of Reading in the U.K., estimated that we have up to a one-in-five chance of being in Maunder Minimum conditions 40 years from now.

We find ourselves in the midst of a planetary experiment. Rigorous science would affirm that the results are unpredictable. Just about anything could happen.

A Helping Hand from the Holocene

In keeping with his low opinion of prediction in science, Dyson does not argue that global warming will continue unabated. He does, however, suggest that a warmer Earth would be a good thing (his lecture, remember, presents five heresies, the first being the bogus nature of climate science). A warmer Earth, he suggests, would likely return the climate to that of the “Wet Sahara” or “Green Sahara” of some 6 kya, when herds of grazing animals, elephants, and even crocodiles were to be found in what is now barren desert.

Here Dyson refers to a period during the mid-Holocene, beginning around 9 kya and extending several thousand years to around 5 kya, a period known as the “Holocene Climatic Optimum” as well as several other terms. The Holocene began around 12 kya; it was a pronounced warming trend in the global climate that marked the end of Pleistocene glaciations. Anthropologists will note that the beginning of the Holocene also marked the origins of agriculture, with the first farming villages appearing in western Asia. Somewhat later, as the Climatic Optimum established itself, some of those farming villages became the nuclei of civilizations. The enterprise we know as “humanity” was transformed, and thanks (or not?) to global warming. Had the cycle of Pleistocene glaciations continued to the present, it is not unlikely that “we” would still consist of scattered bands of hunters chasing mastodons and foragers digging up roots from the half-frozen ground.

The drama of global warming as it correlates with our social origins is marked with irony in these days of shrill pronouncements of impending catastrophe. Imagine those pronouncements being made some 15 kya ago by pundits of time-warped TV networks housed in Manhattan skyscrapers. Tough to imagine, since Manhattan at the time was buried beneath a half-mile of ice which formed part of the Laurentide glaciation. Things change; nothing stays the same; Humpty Dumpty can never be put back together. The remarkable human career over the past three million years rests precisely on our ancestors responding to dramatic and inherently unpredictable changes in their environment. Today global warming, the rise of sea levels, acidification of the oceans, wholesale extinction of species and other, not yet recognized threats to our present way of life may well provide the sort of impetus to transform human life that Pleistocene glaciations and Holocene warmth did for our ancestors. Or they may not. Who knows?

Continuing Dyson’s Heresies: Keep Burning Coal!

The environmentalist narrative embraces and feeds on stark comparisons that are rarely examined closely. Dyson does just that, and, as is his wont, comes up with some striking observations. The widely touted narrative goes like this:

Industrial development in the U. S. and Europe has relied on burning coal and other fossil fuels, which greatly increased the level of CO2 in the atmosphere and caused an alarming spike in global temperatures. Now we in the Western world have seen the error of our ways and are trying to reduce carbon emissions, trying to slow the onslaught of global disaster represented by global warming. However, other nations, particularly China and India, the giants of the developing world, heedlessly continue to burn coal and pump huge amounts of greenhouse gases into the atmosphere. They are ignorant and selfish; we are enlightened and selfless. Something must be done, in the form of economic sanctions or political pressure, to make them stop.

Dyson throws a huge (and greasy, carbon-laden) monkey wrench into this narrative. He argues that a threat to civilization far greater than global warming is unchecked population growth. Each human body represents a strain on the planet’s resources that far outweighs its contribution to global warming. And how to reign in population growth? Dyson notes that the single most successful way to accomplish that is to increase a population’s standard of living. The greater a family’s economic security, the fewer children it will produce. How is that accomplished? By transforming the population from a mass of impoverished peasants working the land with an ancient technology into an urban, industrial society. A society that burns lots of coal. While the environmentalist narrative casts China in particular as the great villain endangering the well-being of the planet, that nation’s economic policy is, Dyson maintains, “both morally and scientifically correct.” As always, things are complicated – and only become more complicated the more closely they are examined.

The “Anthropocene”–Really??

“Anthropocene,” is a term introduced by physical scientists to mark the period, following the Holocene, when human activity purportedly became the dominant force shaping the planetary ecosystem. Since the term is our discipline’s partial signature, a number of anthropologists seem to have adopted it, with the result that “Anthropocene” now appears in the symposium titles of academic meetings, journal articles, and books.

Following Freeman Dyson and George Carlin, I suggest that the term is terribly misleading, and that it prejudices what could be a genuinely dispassionate anthropology of the future.

Carlin stated the case as only he could:

There is nothing wrong with the planet. The people are fucked. Different, different. The planet is fine. Compared to the people, the planet is doing great. Been here four and a half billion years. Did you ever think about the arithmetic? The planet has been here four and a half billion years. We’ve been here, what? A hundred thousand? Maybe, two hundred thousand. And we’ve only been engaged in heavy industry for a little over two hundred years. Two hundred years versus four and a half billion. And we have the conceit to think that somehow we’re a threat, that somehow we’re gonna put in jeopardy this beautiful little blue-green ball that’s just a floatin’ around the sun? The planet’s been through a lot worse than us. Been through all kinds of things worse than us. Been through earthquakes, volcanoes, plate tectonics, continental drift, solar flares, sunspots, the magnetic reversal of the poles, hundreds of thousands of years of bombardment by comets and asteroids and meteors, worldwide floods, worldwide tidal waves, erosion, cosmic rays, recurring ice ages, and we think some plastic bags and some aluminum cans are going to make a difference? The planet isn’t going anywhere. We are. We’re going away. Pack your shit, folks. We’re going away. . .

But where are we going?

Here for Carlin the answer seems to be: oblivion. We’re just another species that will soon join the countless others that have gone extinct over the billions of years of the planet’s history. But Dyson, continuing with his heretical thoughts about science and society, sketches a future even more radical than Carlin’s outright extinction. He suggests that just as computer technology has completely transformed human life during the second half of the 20th century, so biotechnology will bring even more fundamental changes during the second half of the present century. Here a word of caution: If you’re someone who worries that the tomatoes in your supermarket’s produce section may be the dread GMOs – genetically modified organisms – then you’re in for a shock. Dyson sees current efforts at genome tinkering – genetic engineering – as the first tentative steps of a global process that will introduce innumerable new species to the planet. Throw out Linnaeus; the plant and animal kingdoms will never be the same. Worried about extinctions brought on by global warming? Relax – or not – there will be plenty of novel life forms to take their place. Extending this particular heresy, Dyson even suggests that computer video games, so popular today, will be cast aside by future generations of kids addicted to biotech games, eager to see who can create the coolest organism.

Imaginative (or threatening) as Dyson’s prognosis for the future may be, he stops short of posing what anthropologists would consider the crucial next question: What happens to humans in this world of genome tinkering? The only plausible answer is that genetic experimenters (or gamers) will not confine their work and play to plant and animal species, not when the most interesting test subject of all is ready to hand: humans. In a reversal of Doctor Moreau’s gruesome vivisections, intended to refashion animals in the guise of humans, our new genetic explorers may well refashion humans by incorporating a variety of animal genes in their genomes. The future world may be populated by human-human, human-animal, animal-human, and animal-animal beings, hybrids whose rich variety challenges the very concept of “species.” Who knows, some of them may even prefer a Wet Sahara.

While all this may seem bizarre, anthropologists – those self-styled students of the bizarre – should not find the scenario completely alien. A future world of variously sapient beings, living together and interbreeding, is strongly reminiscent of a past world of African savannahs and gallery forests, where a number of Homo lines somehow coalesced into a single species: us. Given our past and possibly future diversity, it seems wrong-headed to insist on a uniform “humanity” that is the yardstick and arbiter of all life forms and modes of life (some like it hot, some not). With this in mind, it is an act of tremendous arrogance to claim that we have crafted an “Anthropocene.”

Postscript

After posting my essay to Ryan, I thought to send a copy to Freeman Dyson, inviting him to contribute comments to our forum. To my surprise and delight he replied the next day. I reproduce his email below:

Dear Lee Drummond,

Thank you for your essay which I enjoyed reading. I agree with almost

everything you say. I would add only one thing that we know for sure.

Carbon dioxide is good for plants of all kinds, natural or agricultural,

wild or tame. Carbon dioxide makes the planet greener. The easy way to

green the planet is to burn more coal. This has nothing to do with

climate. It is just old-fashioned biology.

I am too dumb to follow the instructions about adding a comment to

your forum. If you like to add the comment, I will be grateful.

Yours sincerely, Freeman Dyson.

This is a fascinating case study of the way we tend to think that some general factor of “intelligence” trumps specific subject-matter expertise, as well as the way “physics envy” creates a situation in which physicists are seen as qualified to judge other, lesser fields. I always appreciate when SM gives us the raw data with which do do some anthropological analysis, instead of just presenting the finished conclusions of someone’s analysis!

Consider a bus approaching a cliff. The clueless driver has his foot on the accelerator instead of the brake. The fellow in the back seat says, “Happens every ten thousand years. A bus goes over the cliff.” Should anyone on the bus pay attention to this remark?

There are several things wrong with the bus-over-a-cliff analogy. In the analogy presumably the bus is planet Earth while the riders are the planet’s population. But who is the driver? Is that individual a stand-in for all those greedy, unenlightened types who keep burning coal and ratcheting up their corporations’ profits? The analogy become a little shaky here. Does the driver know she is heading for a cliff? If so, then she’s clearly suicidal. If not, if she’s so intent on profits that she doesn’t see the cliff, then the analogy loses its point. The problem that strikes me most forcibly here, though, is that there is no driver. It’s a driverless bus, or rather, there are a bunch of drivers: all the usual suspects and then some – CO2 levels in the atmosphere, warmer oceans, volcanoes, permutations of the Earth’s orbit, solar activity. With all these trying to drive, the bus really isn’t headed anywhere. Unless you’re 100% committed to the academic fantasy of the “Anthropocene,” and believe that willful human activity directs the planet’s future, then you have to slot all those other factors into your vision of the future. Michael Agar summed it up very nicely in emphasizing that we can’t know where all this will end up: “

We can’t calculate the probabilities because there’s no denominator and the value of the numerator isn’t yet known.”

I could go on and ask, for example, just what is the “cliff”? Complete extinction? Drastic depopulation? Perhaps new forms of sort-of-human life?

But I’ll stop here.

Terrible analogy, as Lee points out. To my mind, normative climate discourse is sometimes so much “Qu’ils mangent de la brioche”, but that’s the point after all.

The “we” of the anthropocene, if unpacked, is informative. To answer an earlier question as regards the future of the anthropocene in anthro, I believe it is here to stay precisely because of this ambiguity. Anthropocene (1) functions too well, rhetorically, as a signal of committed opposition to essentialism and yet (2) is semantically wide open enough to facilitate subordination to any and all of the concerns of critical anthropology. Anthropocene will survive precisely because it prohibits dispassionate analysis.

In other words, physics isn’t so much wrong as beside the point.

A partial response to Dyson’s lecture.

https://patjsheppard.wordpress.com/2012/07/20/a-partial-response-to-freeman-dyson-climate-skeptics/

And another, more complete response:

http://initforthegold.blogspot.com/2007/08/dyson-exegesis.html

Thanks to Michael Thomas and Sean Hall for their thoughtful replies to my essay.

I’ll make two points that apply to both replies, which I hope will lend perspective to the arguments made in my essay.

Point #1 is that I am not a “climate change denier” (although the fact that such a charge is commonly leveled feeds into my Point #2). I am not a climate scientist, still less an environmentalist, but I accept widespread reports that the atmosphere is getting warmer and the oceans more acidic. Given those facts, the crucial question is: Where is all this leading? What will the future look like? Lots of people claim to have the answer, and the answer is very, very bleak. This is where Dyson’s criticism comes in: He claims that for the most part scientists are not, and should not be, engaged in prediction. Particularly when the case at hand is the planetary ecosystem, there are too many variables interacting in only partly understood ways for anyone to provide definitive answers. Here I find Michael Agar’s argument (see his essay, “Betwixt and Between . . .” in this series) both timely and persuasive. Applying complexity theory, Agar suggests that so many things are changing so rapidly that we find ourselves in the early stages of a “phase transition.” Here are his words:

“So does this mean the phase transition is a bitch and then we die? Maybe. The planet will endure, but maybe not us. Does it mean that we will reduce our Earth abuse to the point where a new dynamic equilibrium results in a livable new human/earth coupling that—though different from anything we can predict today—writes a happy ending to our future in Earth’s narrative? Maybe. Does it mean that Earth culls the human herd and corrals it enough to get itself into a new dynamic equilibrium that suits it, with Santa Fe County in New Mexico maybe turning into lush spring rains and gentle winters? Maybe. We won’t know until the transition is over. We can’t calculate the probabilities because there’s no denominator and the value of the numerator isn’t yet known.”

I repeat: “We won’t know until the transition is over. We can’t calculate the probabilities . . .”

In short, we find ourselves in the thick of things, and that, depending on whom you consult, is more or less our doing. But even if it’s more, we still can’t say what the outcome will be.

Now although we are implicated here, a principal argument of my essay is that we’ve been here before (using the term “we” even more loosely than Bill used the term “I”). A wet Miocene, an erratic Pleistocene, a mild Holocene – all these contributed in substantial ways to fashioning what we now know as “humanity.” Humans adjust to changes in their environment, and those changes in turn remake humanity. My point in the essay is that it is impossible to freeze that process, to “go back” to a previous desirable state when the planet was cooler, because dealing with continual change is what “we” are all about. In a separate communication, Agar noted that the phase transitions humanity has experienced – and most likely will continue to experience – are nothing compared to the Mother Of All Extinctions about 2.5 billion years ago when Earth’s atmosphere experienced a large buildup of oxygen. Oxygen was a deadly poison to organisms that then inhabited the planet; they died off in droves. Now, of course, oxygen is the breath of life. If cyanobacteria could have mounted an environmental movement . . .

This nudges me into Point #2. I am a cultural anthropologist, not (obviously) a climate scientist, and one of my particular interests is popular culture – loosely defined, those aspects of contemporary life that get lots and lots of people interested and involved. Whatever the science, I think it is clear that “climate change” has become a fixture of popular culture. Government officials, representatives of NGOs, academics, cable news anchors, editorial writers, talking head commentators of every stripe, and countless private citizens have raised a clamor impossible to ignore. The cultural anthropologist must approach that on its own terms. Here I’ll again have recourse to Dyson’s remarkable lecture. Dyson claims that on any objective scale, a far greater threat than climate change to human survival is overpopulation. Yet in recent decades comparatively little has been said or written about that problem. Why this should be the case I must leave for another occasion – I do have cultural analytic interpretations at hand. The gross disparity does suggest that the furor over climate change is something of a fashion statement – although to claim that merely shifts the analysis to the topic of “fashion.”

Instead, let me cite a tragic case: the plight of Syrian refugees. That has displaced even climate change in the 24/7 news cycle, but no anthropological explanations that I know of have been advanced. I suggest that the phenomenon of overpopulation, thoroughly downplayed in the alarm over climate change, can’t be overlooked here. For there are so very many refugees. In 1980 the population of Syria was around 8 or 9 million. In thirty years or so, just before the civil war, it had swelled to around 22 million. Now some 6.5 million, nearly equal to the former population, live as displaced persons within Syria, sheltering from the barrel bombs, hiding from ISIS thugs. Another 5 million or so – those who now get all the attention – have become international refugees. The scale of it is numbing. More, lots more Syrians have run for their lives than existed thirty-five years ago. Why so much focus on climate change; why so little on overpopulation? Dyson’s question, and mine.

It’s clear from my essay that I’m not a big fan of the current hot topic, the “Anthropocene.” In trying to get a handle on the concept, I wind up being more confused by what I read about it. For example, in his thoughtful reply to my essay Michael Thomas writes that “Anthropocene functions . . . as a signal of committed opposition to essentialism.” So now I have two concepts that bother me. Whenever I find the dreadful charge of Essentialist! being leveled at someone or some piece of work, my eyes cloud over and I quickly turn to something else. I won’t launch into a full critique here, because what I think is especially odd (and downright paradoxical) about our current case is that, as nearly as I can decipher, the concept of the “Anthropocene” is itself shot through with “essentialism.” Doesn’t that concept rest on the premise that there in fact exists some discrete, bounded entity – humanity, anthropos – whose actions affect its environment to such an extent that the environment acquires fundamentally new characteristics? Isn’t that premise “essentialist”? Tell me what I’ve missed here.

My confusion is compounded by an earlier essay in this series, “Is There Hope for an Anthropocene Anthropology?” by Todd Sanders and Elizabeth Hall. Their argument is that adopting the concept – and making it the basis for all anthropological inquiry – will rescue us from the tired old way of looking at things that prevailed until Hope bloomed:

“For as we enter the Anthropocene, we’ll need new conceptual tools and ways of thinking to understand our new home. The familiar dualisms that have long dogged our discipline and world – Nature and Culture; local and global; Moderns and non-moderns; and so on – are not up to the task. Discard the Modern dualisms. Dwell on the emergent processes of their production.”

I know I’m old school, but I thought those “familiar dualisms” – particularly Nature vs. Culture – had been (dare I say) deconstructed in anthropology a long time ago. By Gregory Bateson. Surely his work and thought still have some relevance even now, after all, the folks at the Society for Cultural Anthropology pass out awards in his name. Bateson’s titles alone strongly suggest his monist thinking: Steps to an Ecology of Mind, and, if that doesn’t provide enough of a clue, Mind and Nature: A Necessary Unity. For Bateson, human behavior is not something applied to or acting on an external environment; the behavior and environment are indissociable elements of a whole. I won’t use up space here providing examples; those are ready to hand in his books. Which, incidentally were published nearly a half century ago. Striking down dualisms is not a last-minute ticket to a brave new world of an “Anthropocene Anthropology.” We, or some of us, have been at it for a while.

Funny. There’s a game the US government is helping to fund that’s supposed to help teach kids about environmental science, and the only article that goes into any real detail about the science and educational theory and methodology behind it makes no mention of global warming: http://massivelyop.com/2015/09/30/exploring-modern-online-game-research-and-the-video-game-debate/

You say your and Dyson’s question is: Why so much focus on climate change and so little on overpopulation? That’s not all Dyson is doing though. He’s also criticizing climate science and seems to be doing a very poor job of it. Whatever his opinion on how much focus there is on climate change that’s no excuse for spreading false information about it. You acknowledge you are not a climate scientist. Dyson seems to assume that his expertise in physics automatically makes him an informed expert on climate science. As a result, he is spreading uninformed ideas about climate science that are erroneous.

Also, it seems a fallacy to me to suggest that focusing on one of those issues requires excluding the other. Instead of asking why so much focus on climate and so little on overpopulation we can simply ask: why don’t we talk more about overpopulation? The previous question assumes that climate change is the ONLY reason we don’t talk more about overpopulation. While there’s certainly not as much talk on overpopulation there is some talk. A quick google search got me four articles (posted below) from 2006-2015 with opinions ranging from a calm ‘We’re not sure if overpopulation will be a big deal’ to an alarmist “OMG human beings will go extinct!” If Dyson is really concerned about overpopulation and wants more people talking about it wouldn’t he better served to focus on that instead of feeding the ‘controversy’ of climate change?

Frankly, I think Dyson’s argument that climate scientists shouldn’t attempt predictions is absurd and potentially disastrous. He says there are too many variables to make accurate predictions but again, he’s not a climate scientist, and this criticism amounts to mere opinion. I’d say that in fact, as far as human beings dealing with changes in our environment is concerned, that climate science is now critical to our understanding of what we face. Is it essential to preventing our complete extinction? Maybe, maybe not. But why on earth take the risk if we have the ability to make some predictions? To have some idea of what to prepare for? I would add that there are also many variables in trying to determine the future consequences of population growth. How is attempting to determine the future consequences of population growth, or even simply how much growth there will be, any less of a prediction than the future effects of climate change?

http://www.scientificamerican.com/article/human-overpopulation-still-an-issue-of-concern/

http://www.nytimes.com/roomfordebate/2015/06/08/is-overpopulation-a-legitimate-threat-to-humanity-and-the-planet/overconsumption-is-a-grave-threat-to-humanity

http://www.independent.co.uk/environment/overpopulation-is-main-threat-to-planet-521925.html

http://www.marketwatch.com/story/climate-report-proves-humans-are-the-new-dinosaurs-2013-10-12

Sean,

Thanks for continuing our exchange regarding this vital issue. As I suggested in my previous reply, I think we are addressing two separate but related but issues.

The first issue is the status of models of climate change in the context of Earth’s always evolving ecosystem. My main point here is that available information from paleontology indicates that the planet’s climate has experienced dramatic changes throughout hundreds of millions of years, and there is no reason to think that process will change anytime soon. Right now, despite a couple of hundred years of industrial activity, Earth is still much cooler than it’s been for ages past: We’re in the planet’s “Icehouse Earth” phase. Will that process suddenly change catastrophically, with the geological past becoming irrelevant in the face of continuing human action? Perhaps, but that suggestion comes with a serious problem. As Michael Agar argued in a previous essay in this series, erratic changes in climate indicators may indicate that the planet is in the midst of a “phase transition.” If so, Earth as a dynamic system switching from one phase to another is too complex to model; accurate prediction is impossible. As Michael notes, we’ll just have to see what happens. Dyson is not a climate scientist nor, as I noted and you kindly pointed out, am I. However, there does seem to be expert disagreement over whether disaster is imminent, and not just from the wing nut crowd. Which brings me to the second issue.

“Climate change” is not just a scientific debate; it is now very much a political hot button topic and as such is in the province of ideology (culture). Cultural anthropologists, whether or not they know beans about climate models, are well qualified to weigh in here. And with climate change part of the 24/7 cable news cycle and of presidential debates, I think we should recognize that it is now a fixture of popular culture. As someone who’s spent a lot of time thinking and writing about American popular culture, I perhaps flatter myself that I can make a useful contribution to current debate.

One major puzzle I noted right away – following Dyson – is that climate change has become the focus of near hysteria on the part of Western governments and media, eclipsing a problem that some think looms even larger: overpopulation. Since The Limits to Growth was published nearly half a century ago, I can think of no international document of comparable stature that addresses population growth. No Kyoto Protocol, no U. N. resolution, no urgent meetings of ministers. In the meantime, of course, we’re flooded with official pronouncements at every level decrying the climate crisis. Others have noted and criticized this huge disparity. I thank you for supplying a reference to one such criticism, published ten years ago – well before things had heated up to the current level of polemic. An excerpt:

“Climate change and global pollution cannot be adequately tackled without addressing the neglected issue of the world’s booming population, according to two leading scientists.

Professor Chris Rapley, director of the British Antarctic Survey, and Professor John Guillebaud, vented their frustration yesterday at the fact that overpopulation had fallen off the agenda of the many organisations dedicated to saving the planet.

The scientists said dealing with the burgeoning human population of the planet was vital if real progress was to be made on the other enormous problems facing the world.

“It is the elephant in the room that nobody wants to talk about” Professor Guillebaud said. “Unless we reduce the human population humanely through family planning, nature will do it for us through violence, epidemics or starvation.”

http://www.independent.co.uk/environment/overpopulation-is-main-threat-to-planet-521925.html

I strongly recommend readers consult the entire article.

Why the disparity? In my first reply I mentioned that I think cultural analytic explanations are worth considering. This is a complex topic; here I will merely flag the direction of one such analysis:

Campaigning against global warming means confronting corporations and foreign governments, holding them to blame for the phenomenon. However, any serious effort to mount an international program aimed at slowing population growth involves some official somewhere inserting himself into people’s lives on a very personal basis: questioning them about their sexual activity, offering contraceptives, perhaps counseling abortion. Obviously, this course of action easily generates hostility – just look at the firestorm over Planned Parenthood and abortion now consuming the modern enlightened democracy of the U. S. How can we expect it to play out differently in the non-Western world?

Faced with this impasse, government agencies that might have done something as Earth’s population ratcheted past seven billion seem to prefer to devote their energies to slowing global warming.