Encounters with art and design by an anthropologist and curious non-expert in visual culture.

Since starting to work alongside an artist and a designer, I’ve become more aware of ethnographic practice inflected by art and design. There seems to be a growing number of institutional spaces, degree programs, courses, workshops and books devoted to exploring different combinations of art/design aesthetics and ethnography. While audience and aims vary, one can’t help but wonder what it means for there to be a kind mushrooming of art/design inflected methods and outputs (Design Anthropology, Anthropology Design, Design Ethnography, Sensory Ethnography to name a few and see for instance a last year’s ANTROPOLOGY + DESIGN series on Savage Minds). While visual anthropology has an extended history, and anthropologists have long been interested in the intersections of aesthetic and cultural production, is there something of a “visualisation of anthropology” (Grimshaw & Ravetz 2005) underway? Is an attention to art and design in anthropology ‘new’ or simply new to me? For those of us not designated as ‘visual’ anthropologists, are we being asked/invited/demanded to engage with different modalities for fieldwork and scholarly output?

I decided ask an expert. Keith M. Murphy is an anthropologist of design. His new book Swedish Design: An Ethnography is just that. It is a rich description and analysis of how everyday things (furniture, lighting) are made to mean through processes of design within the context of larger cultural flows. Like some of the iconic objects he describes, Keith’s writing is sharp, uncluttered and politically aware.

In addition to researching and writing about design, Keith experiments with how to harness design modalities to anthropological and ethnographic practice. Through the Center for Ethnography at the University of California, Irvine, Keith and George Marcus host occasional events called ‘Ethnocharettes’. An ethnocharrette is described as a collaborative session of intense activity in which design thinking and methods are used to interrogate and explore ethnographic concerns. Their most recent installment was in March. I was fortunate enough to be there and do what anthropologists do best: hang out, watch, listen, and ask questions.

I reached Keith at his standing desk in his Long Beach home via FaceTime. Our conversation tacked back and forth between the particulars of the ethnocharrette exercise and his speculations on why ‘the visual’ and borrowed modalities from art and design seem to be growing new roots (routes) in anthropology. It was less of an ‘interview’ and more of an ongoing conversation we have been having for the past year or so. I re-assemble our discussion over two posts and invite you to join the conversation.

Before I arrived in California, Keith described the ethnocharrette to me as “this thing”. The ambiguity of his shorthand reflected the changing form of the event since its inception. A charrette is a common activity in design disciplines. Keith described it as more than brainstorming, less than consequential. It is inherently collaborative. Whereas a classic brainstorm involves individuals tossing out ideas and then selecting ones to choose, a charrette is designed collaboratively create by bringing things together.

The impetus for the ethnocharrette experiment came partly from Keith’s own exposure to design thinking in his research, through an earlier pre-doctoral internship at Sapient, and from working briefly as a member of the COLAB team at Syracuse University. Since Writing Culture, George Marcus has increasingly been interested in exploring the appeal of design and the studio as a legitimate form of experimentation in association with fieldwork projects. Keith was upfront that as a pair they have been willfully sidestepping the issue of whether the charrette model is for pedagogy or ethnographic practice. It has always been done in the context of pedagogy (graduate student training), however they have found the boundary between pedagogy and practice blurred by students themselves. Some of the techniques introduced pre-fieldwork end up being independently taken up by students as they move into their analysis and writing.

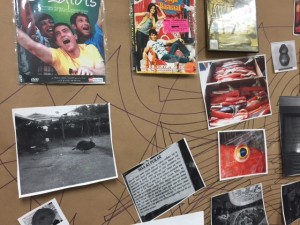

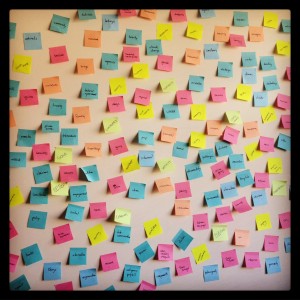

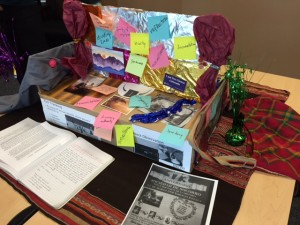

The most recent iteration involved students bringing ‘ethnographica’ related to their projects. They were instructed to bring ‘things” (texts, images, objects, sound files) that were easily displayed and shared with others. They were in groups of three to five and had each selected a theorist to think through their materials with. Phase one of the charette involved students giving brief introductions of their materials and then laying out ‘pieces’ of their selected theory on post-its. The culling for simplified parts and constraining them to a post-it is an attempt to disturb anthropology’s penchant for the complicated. “If anthropology had a tombstone it would say ‘its complicated’ ”, remarked Murphy. The charette is designed to extract information from materials before deep thinking. This slows down the desire to ‘complicate’ and take better stock of what is.

Once the theory pieces are up, students are invited to ‘read’ each other’s materials. The ethnocharette works against the normative model of anthropological production where singular people are doing work on singular projects. Instead of having students trained to think as individuals first, collaborators later, the charrette model introduces co-thinking earlier in the academic process. Of course there are long lists of successful collaborations from our field, yet individual projects continue to be favoured and rewarded. In the exercise, students relinquish sole ‘ownership’ over their materials and see the variety of ways in which they can be read. Again, post-its keep track of pieces.

Next, students look at the bits of information they have co-produced and think about how they might sensibly cluster. They can re-arrange and combine them in ways they see fit. Keith describes this as ‘structured non-thinking’. The process asks them to physically relate to materials in different ways. Instead of solely cultivating habits like sitting, thinking, attacking, the charette has people standing, moving, touching and seeing things differently. The groups I observed related to the task in different ways. Some had highly tidy rows of like terms, others had stacks of ideas, while one group was determined to extract from us the ‘correct’ way of proceeding.

Phase two of the charrette asks participants to take what has been assembled and re-present it in light of the process. The idea is that if Phase I is a process that compels the participants to let go of their pre-conceived commitments to their field sites and ethnographic materials, and to find otherwise unnoticed connections between their individual field sites, Phase II is intended to push students to create something — a rough material or conceptual prototype — that could account for these new connections in unforeseen ways. Theory is important here, too. Each group worked with a specific theorist, and tried to incorporate those ideas into their prototypes as glue that held the disparate projects together. Again some groups quickly set about creating, while others waded through possibilities with some uncertainty what could/should be done. Keith sees this hesitation as part of the ‘ideology of creativity’ that design rests on. Design assumes everyone is creative, whereas many anthropologists assume they aren’t creative. In fact, there are explicit discourses against creativity. The charrette is meant to interrupt some of these [stereotypes] to push the boundaries of what anthropology can be, while not oversubscribing to ‘creativity’ as inherently valuable (sellable).

Here I objected. My migration to anthropology from sociology/ applied linguistics was precisely my sense that there was space for creative scholarly practice and that corners of the discipline were staunchly uncommitted to a sharp divide between art and science. If anything, I remarked, I over estimate my creativity. He reframed. The question is perhaps less about if you are creative, but rather what opportunities do you have to manifest creativity? He had me there. While I have been fortunate to be part of Ethnographic Terminalia in the past, most creative projects have been taken on through art-based residencies rather than academic ones.

I still wanted to push the issue of creativity. The analysis seems gendered. Many women anthropologists take on creative modalities (literary ethnography, creative non-fiction) and while they find an audience in the Real World, they can sometimes seem ‘niche’ in mainstream anthropology. Keith acknowledged that there is a difference between certain kinds of aestheticizations and the regimes of value they find themselves circulating in. Broadening what it means to be ‘creative’ as an anthropologist is about understanding stylizations (creative non-fiction, or jargon laden prose) do stand for themselves as inherently valuable. Rather the question must be asked, what are you attempting to do? Who is the audience? What’s the goal? Ethnocharrette is just a part of a longer conversation that students’ work will be in over the course of their training.

Our own conversation moved to the bigger picture. Later that week, he and I would join a larger group of faculty and advanced graduate students for a Productive Encounter led by anthropologist Christine Hegel and set designer Luke Cantarella. We would be making use of design exercises to think through Doug Holmes’ work on central bankers. Perhaps as a result of my own training, I was inclined to ask the question, ‘why this, why now?’ Why are these modes of thinking/ practicing anthropology appearing? Our conversation continues in my next post.

Great stuff. I am looking forward to the next installment. Especially interesting just now, since I am expanding a presentation at IUAES 2014 on “Conditions of Creativity” for the Journal of Business Anthropology. A point you might want to consider is the difference between the charettes you describe and the way that creative teams are structured in the advertising world. Charettes as you describe them bring together people who may have different personalities and different bits of personal knowledge to bring to the table, but they share the same roles — student or teacher. Creative teams are composed of individuals selected because of specific skills that enable them to play particular roles, e.g., the following list for a simple print ad: Creative Director, Copywriter, Art Director, Designer, Photographer or Illustrator. TV teams are more complex, with Producers, Directors, Cinematographers, Music and Lighting Directors, Film/video Editors, Sound Engineers, Stylists, Hair and Makeup Artists, etc. The influence of personalities and personal knowledge is filtered by these roles. Who is selected to play the roles depends both on desirability [stylistic fit with the project and reputation] and availability. The Creative Director may know the perfect Cinematographer to realize the team’s creative vision; but if that individual is already committed to other projects or working for a rival agency, he or she will not be used. I find myself wondering if design industry charettes differ from academic charettes in a similar manner.