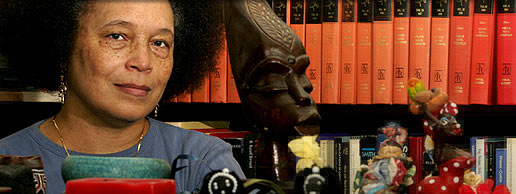

[Savage Minds is honored to publish this essay by Faye V. Harrison who is currently Professor of African-American Studies at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, and President of the International Union of Anthropological and Ethnological Sciences. She is the author of numerous articles and books, including the landmark volumes Decolonizing Anthropology: Moving Further Toward an Anthropology for Liberation (American Anthropological Association, 1994) and Outsider Within: Reworking Anthropology in the Global Age (University of Illinois Press, 2008).]

Like hundreds of others, I participated in the December 5th die in at the American Anthropological Association meeting in Washington, D.C. Under the leadership of the Association of Black Anthropologists and galvanized through the ABA’s alliance-building with other kindred-thinking AAA sections, the main lobby of the Marriott Hotel was converted into a symbolic space of social death for four and a half minutes. Darren Wilson and his fellow Ferguson, Missouri police officers left the lifeless body of teenager Michael Brown in the middle of the street for four and half hours before it was covered up and taken away. Four and a half hours of exposure to the elements; four and a half hours of utter disrespect for the loss of the young man’s life and disrespect for the family and community that would grieve the killing of yet another son on blood-stained ground. A blood-stained landscape of social and real-life death links Fruitvale Station in Oakland, California to Ferguson, Missouri and countless other sites across the nation and the world, where the lives of blacks and other people of color are being targeted for harassment, arrest, incarceration, and, in the worst case scenario, elimination and disposal.

In the racialized spaces of social death wherein Black lives are rendered less than fully human, Black male and female encounters with police and also with the vigilante violence of citizens enacting a stand-your-ground logic have disproportionately resulted in the wrongful deaths of unarmed adolescents and adults, sons and fathers like Staten Island, New York’s Eric Garner. It’s imperative that we understand that daughters, mothers, and grandmothers are not immune to this kind of existential vulnerability. The Black females who have died from wrongful police killings—including 93 year-old Pearlie Smith and 7-year old Aiyana Jones—have been much less visible in the media and in mass protest action. This phenomenon results from a racialized gender bias that needs to be better understood so that it can be effectively redressed.

A tragic pattern prevails across the land; it represents an escalation of extrajudicial executions targeting black and other dark(ened) bodies, whose culpability is conjured through criminalizing accusations. They are guilty of driving, walking, talking back, and, in the case of Jordan Davis in Jacksonville, Florida, even of listening to loud music while Black. The widely shared presumption is that these targeted individuals were dangerous threats to law and order and to personal security, particularly white people’s safety and undisturbed peace. The controlling image or stereotype of the violently aggressive thug has been indiscriminately projected upon black bodies, particularly those performing black masculinities. The refusal of grand juries to indict and, in the case of trials, of juries to convict the rightful perpetrators of this violence reflects the extent to which black lives are devalued and infra-humanized in this society. It is for this reason that protesters all across the country and even our allies in other national settings are carrying signs asserting that “Black Lives Matter!” and exhorting “Don’t Shoot!”

These poignant declarations resonate with those being made in public protests against the undeclared war on black youth in Brazil, where the pacification of poor neighborhoods, to make way for the World Cup and Olympics, is intensifying the already existent racially-marked violence of police and privately-commissioned militias—death squads—that participate in the ethnic/social cleansing of urban and rural space. The coercive dislocation and elimination of black people is an integral feature of the systematic land grab that Keisha-Khan Perry brilliantly analyzes in her award-winning ethnography, Black Women against the Land Grab: The Fight for Racial Justice in Brazil (2013). Other anthropologists working in Brazil are also documenting these trends, such as Christen Smith and João Costa Vargas. Vargas analyzes them in terms of an anti-black genocidal continuum which also exists in other African diasporic settings, including the United States.

Human rights reports have also documented the extent to which racial profiling, extrajudicial executions, and police impunity are troubling trends in both Brazil and the United States of America. In 2009 two relevant documents were issued: Human Rights Watch’s Lethal Force: Police Violence and Public Security in Rio de Janeiro and São Paulo and the UN Special Rapporteur on Contemporary Forms of Racism, Racial Discrimination, and Related Intolerance’s follow-up report on the implementation, or lack thereof, of the Durban Declaration and Program of Action. I am referring specifically to the addendum on the internationally renowned lawyer and legal scholar Doudou Diène’s 2008 mission to the United States. A major portion of his report dealt with law enforcement, which rivaled with immigration control and counterterrorism as a context for racialized human rights abuse.

Our declarations of “Black Lives Matter” also resonate with the human rights protests all across Mexico, where 43 students, many if not all from poor indigenous backgrounds, disappeared from a teachers college in Iguala, Guerrero in September. They were abducted by police and handed over to a drug gang that murdered them, if rumors and initial forensic evidence are accurate. That the lives of those 43 students matter has been collectively expressed in demonstrations and declarations demanding that the federal government hold the instigators and perpetrators of the crime against humanity accountable and return the students to their families and communities—that is, if they are still alive. However, if the students have perished, the government has the responsibility to conduct a comprehensive investigation and provide a public explanation of what happened and why. And it has the responsibility to punish the culprits, going against the grain of a political culture of impunity and corruption.

On November 25, 2014, the International Union of Anthropological and Ethnological Sciences (IUAES), of which I am currently president, published a brief statement in solidarity with Mexican and Latin American protesters, who include anthropologists, on the opinion page of the newspaper La Jornada. Like Ferguson, Mo., this is a tragic case of youth from oppressed communities being targeted by repressive social control practices, from militarized policing and para-militarized repression to a whole range of neoliberalized modes of governance. As an anthropologist, a concerned citizen, and a mother, my mapping of human rights violations zooms in on my own backyard as well as in more distant zones of power disparities.

The four and a half minutes we all lay in complete silence on the lobby floor were quite intense. I filled my mind with meditative thoughts of Michael Brown, Trayvon Martin, and their parents, who channeled their profound grief and sorrow into internationally visible activism. I also saw the faces of my own three sons, now men. I remembered when I delivered the eldest during an unexpectedly difficult and protracted labor. Anxieties mounted within me about the challenges I would face of raising a Black male child in a racist society in which a threatening otherness would be attributed to him. I suspected that much of the discrimination he was likely to face would be much more subtle than what his father and grandfathers had known. But what I feared most and couldn’t get out of mind was the specter of brutal police force and the potential hate crimes to which he might be subjected. I wondered whether, as a parent and a member of a wider family and community, I would be sufficiently able to protect him and to guide him into full adulthood. I meditated and prayed that I would be able to meet the challenges and demands of Black motherhood.

As I labored with all my might to give birth to my baby boy, my man child who would be born into an unfulfilled promise land, I questioned whether the neoliberal logic likely to be applied during the 1980s Reaganomics regime would lead to a milieu marked by even more dangerous racializing meanings, conditions, and practices, contrary to the expectations born of civil rights era optimism. Years later I would come to know that so much of the research anthropologists have done on the neoliberal landscapes of the past three decades have illuminated the troubling effects of structural racism’s persistence and remaking in its entanglements with other dimensions of social inequality and conflict—class, gender, sexuality, and generation or age. However, the current conjuncture, articulated now as the Age of Ferguson, has severely challenged the optimism that many antiracist liberals and leftists have long embodied about the extent to which our society has changed for the better and is capable of changing at a positively discernible pace.

The depth, intensity, and pervasiveness of anti-blackness in the fabric of U.S. society compel us to rethink our models of and for social transformation. Those who subscribe to more pessimistic perspectives, such as scholars and activists associated with the Derrick Bell-variety of critical race theory and the intellectual trajectory known as Afro-pessimism, urge us to relinquish our political naïveté in favor of a more critically realistic views of what is, what is possible, and what should be done about them. Whether optimist, pessimist, or somewhere in between, perhaps we can agree that the “Black Lives Matter,” “Don’t Shoot” and “I Can’t Breathe” demonstrations proliferating across the country clearly belie the widespread postracial pretensions and conceit that have denied grievances against racism the legitimacy as well as the political and policy attention they rightfully deserve.

The four and a half minutes were over. After getting up from the floor, I interacted with the two women who were nearest to me. One remarked on how intense those few minutes of silence had been for her. I agreed, as I wiped away tears streaming from my eyes. After exchanging our feelings and reactions, we gave each other a big group hug and expressed sincere thanks and appreciation for having experienced the die in with colleagues whose knowledge, sensibilities and politics we respected. That night at the AAA Business meeting, after a prolonged debate on a contentious resolution not to support the boycott against Israeli academic institutions, which was voted down, a motion from the Section Assembly was passed without any opposition. The motion called for the association’s making a public statement on Ferguson and Staten Island, appointing a task force to determine what anthropologists can do to address racialized policing, and urging the U.S. Department of Justice to investigate extrajudicial violence and killing. Many of us left the AAA meeting feeling that anthropologists can and will find meaningful ways to play a part in the struggle, as it will continue to unfold in the years to come. La lucha continúa. A luta continua. The struggle continues.

0 thoughts on “Reflections on the AAA Die-in as a Symbolic Space of Social Death”