In my last post on Bauman and Briggs Voices of Modernity I explored their argument that Boas’s notion of culture makes it seem like a prison house from which only the trained anthropologist is capable of escaping. In doing so, however, I only really presented half of their argument. The book has two interrelated themes: One is a Foucauldian genealogy of the concepts of science, culture, race, language, and nation (as seen through the rise of folklore studies). The other is a Latourian exploration of the construction of folklore as a science. This is done by exploring how oral traditions were turned into texts, and thus evidence of traditional culture (however that was defined). Aubrey, Blair, the Grimm brothers, and Schoolcraft were each faced with hybrid oral texts whose own modernity (as contemporary documents) belied their perceived scientific value as authentic remnants of ancient cultures. For this reason the texts underwent tremendous alterations, if not outright fabrication, by these scholars in order to make them suitable for their own purposes. The book traces how these processes of entextualization were shaped by each scholar’s concepts of science, culture, race, language, and nation.

So where does Boas fit into all of this?

One of the legacies of earlier folkloric traditions was a view of contemporary oral traditions as little more than the decayed remnants of a once great culture. Although Boas was able, partially as a result of his linguistically inspired view of culture, to criticize evolutionary perspectives that placed contemporary indigenous people in the past, he still seems to have shared some of these views.

Boas was particularly interested in what he considered to be traditional speech. This quest for the archaic and authentic related to form as well as content; Boas summarized his agenda as an attempt “to rescue the vanishing forms of speech”

This rescuing entailed some of the same reconstruction that earlier folklorists were guilty of. In some cases, such as Blair, this entailed the wholesale fabrication of supposedly traditional folktales. In others, such as the Brothers Grimm and Schoolcraft, it entailed heavy editing and embelleshment (although they each did this in different ways and for different reasons – discussed in depth in the book). Boas, however, was even more concerned than his predecessors about establishing the scientific credentials of his work. But his vision of fieldwork as science usefully served to hide some of his entextualization practices from public scrutiny.

Fieldwork became a complex set of practices that had to be mastered through professional training; like owning an air pump, controlling access to this pedagogical process enabled Boas and those he trained to regulate the obligatory passage points that provided access to cultural knowledge. The analogy begins to break down, however, in that the air pump was designed to produce public knowledge, to open scientific work to scrutiny by groups of observers. Fieldwork placed the locus of observation far away from the center. Since people’s perceptions of their own cultural patterns are shaped by secondary explanations, Boas does not deem “natives” to be credible witnesses.

Here is where the questions of anthropological authority discussed last week become important, for while Boas is famous for having worked closely with indigenous scholars, even going so far as to give them credit for published work, the actual manner in which the texts were constructed still reveals some of the same discomfort with the hybridity of these texts that was shown by his predecessors. To understand this argument we need to know something about one of the scholars most closely associated with Boas, George Hunt:

George Hunt was the son of a high-ranking Tlingit woman and an Englishman who worked for the Hudson Bay Company. Hunt was raised in Fort Rupert, a stockaded outpost and Hudson Bay Company station that brought together not only Kwakwaka’wakw but also English, Scots, Irish, French-Canadian, Métis, Iroquois, Hawaiian, Tlingit, Tsimshian, and Haida… Hunt was perceived as a “foreign Indian” by the Kwakwaka’wakw, and he never considered himself to be Kwakwaka’wakw; he often re-ferred to his wife’s relatives as “these Kwaguls.” At the same time, Hunt’s noble descent brought him high status, particularly after he married a high-ranking Kwakwaka’wakw woman. Hunt’s rank afforded him exposure to forms of knowledge and discourse owned by elite lineages, and it granted him a strong social position by virtue of the high-ranking lines’ dominance of trade and indigenous–white relations.

So how did their collaboration work?

Hunt did not take down material by dictation, but rather listened to the rendition and then went home and reconstructed – and thus re-entextualized – the discourse; after he had written the text in its entirety in Kwakw’ala, he added English interlineations. As he rephrased the materials in the written version, Hunt wrote in what Berman (1996) refers to as “an authentic Kwakwaka’wakw speech style formerly used in the myth recitations,” even when his consultants are likely to have used less archaic styles. Hunt attempted to locate and document speech styles that he deemed to be particularly traditional and authentic; regarding some of his texts on cooking, Hunt wrote Boas: “These will show you the oldest way of speaking.”

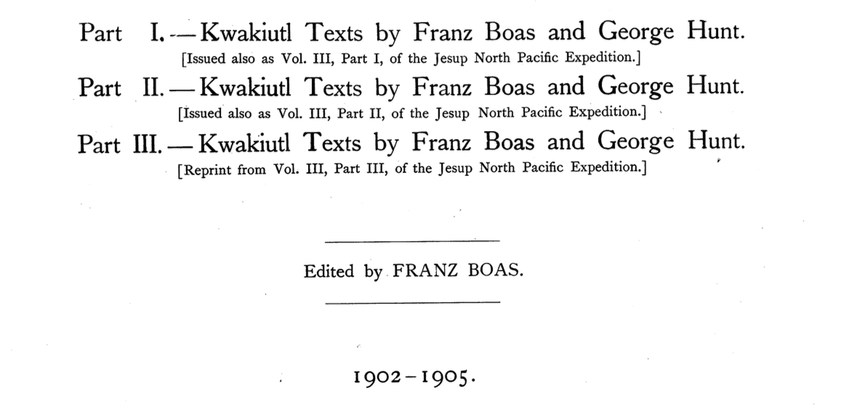

One of the implications of this is that Hunt, as the “native informant” allowed Boas to sub-contract and legitimate the work of re-entextualization, effectively brushing the dirty work associated with creating these texts under the carpet. So while Bauman and Briggs want to give “credit where credit is due” and praise Boas for sharing authorship with Hunt on the title page (see the image at the start of this post), they have reservations about how Hunt’s authorship was framed.

The voice that Boas sought to authorize, however, was not that of George Hunt qua individual, not in terms of the particular features of his complex, hybrid social position. Rather, Boas downplayed Hunt’s background, including his multiracial ancestry in characterizing Hunt as speaking “Kwakiutl as his native language.”

Boas needed Hunt to give scientific authority to his texts, but in order to construct that authority he had to downplay the true hybridity of Hunt’s background.

Foregrounding the cultural and historical complexity of the texts and the circumstances surrounding their production would have challenged the way that Boas was constructing their authority – as a voice that could speak for “Kwakiutl customs” in their entirety… By giving the impression that members of Kwakwaka’wakw communities spoke no English, Boas greatly increased the monologicality and monoglossia of the texts and removed another sort of important evidence with respect to their rootedness in colonial contexts.

So, while Boas deserves credit for granting Hunt co-authorship, we can still question the manner in which he did it and even his motivations. None of this is to play a game of “gotcha” with Boas, but to get us to think critically about our own practices of entextualization and our own contemporary mechanisms of granting ourselves anthropolgical authority.

I find Bauman and Briggs’ work salutary insomuch as it makes clear that Boas’s framing of things oversimplified the matter. And I find it perfectly reasonable to flip that back on them. Vis-a-vis Hunt’s background, I don’t quite understand how individual and social position stand in opposition to one another. In any case, there is plenty of work out there that suggests that complexity and hybridity are the everyday way of things in the Pacific Northwest, so Hunt’s might even be considered representative in that sense.

Why Boas should have been expected to play up, much less mention, Hunt’s multiracial ancestry I do not know. Even outside of the context of Pacific Northwest social life that’s an odd comment coming from two authors who do seem to understand that a big part of Boas’s work was the uncoupling of the concepts of race, language, and culture.

I honestly don’t know what I think about the book. The authors are clearly possessing of first rate intellects and rhetorical skills. I guess it hints of sophistry to me; whether in the classical sense of the term or the contemporary, I am unsure.

Question: Is there anyone here, reading this post, who claims “anthropological authority”? I have known a variety of anthropologists over the last half century or so, and I cannot, for the life of me, recall any who claimed to possess authority because they were anthropologists. Outside of classrooms, any of them who stepped into a situation and said, “I am an anthropologist” in the same let-me-handle-this tone as a doctor might say, “I am a doctor” or a lawyer might say, “I am a lawyer” would have seemed ridiculous.

The material about Boas and Hunt is fascinating. But the reconstruction of texts as they are recorded, transcribed, translated, and edited for publication, then presented as an example of something traditional is hardly something that only anthropologists do. “To translate is to betray” is an old, old saw.

What, then, concretely does “considering our practices of entextualization” do to improve anthropology? I could use some help here.

John McCreery raises a bottom line question: “What, then, concretely does “considering our practices of entextualization” do to improve anthropology?” It seems to me that other than reminding us again that we are “authors” of “texts” (which Clifford Geertz explicated in Works and Lives), there is not much here to work with. I appreciate the thinking but I am exhausted by the prospect of another form of anthropological paralysis, in this case, the lack of complete verisimilitude that occurs in the process of translation.

I find Bauman and Briggs’ work salutary insomuch as it makes clear that Boas’s framing of things oversimplified the matter.

Come now. No finding is more routine. Every framing oversimplifies the matter under discussion.

Why? Because, as Boas’ student Edward Sapir taught us in Language, this is a property of all human languages. We cannot speak in particulars, we always speak in concepts, and concepts as such always omit an infinite host of particulars. Thus, the critic who says an author failed to consider X, Y or Z has said nothing useful at all unless he or she can offer an alternative framing that includes accounting for the additional detail in question.

Assume for the sake of argument that George Hunt provided Boas with erroneous translations of a biased sample of First Nations texts, which Boas then treated as exemplars of First Nation tradition. There are plainly questions to be asked. Does a closer, more careful reading with more turns of the hermeneutic cycle reveal issues that Boas missed? Are there alternative texts for comparison? Have First Nations representatives with alternative interpretations demanded to be heard? What axes, if any, do they — and Hunt before them —have to grind?. . . .

That said, to “indict” a revered ancestor because he failed to be God Almighty and tell the whole truth, which no mere human can know—that seems to me intellectual hubris in the last throes of despair.

“The other is a Latourian exploration of the construction of folklore as a science. This is done by exploring how oral traditions were turned into texts, and thus evidence of traditional culture.”

This enterprise of Boas and other folklorists puts me in mind of individuals such as John Ruskin, William Morris and the striving for Gothic Revival by architects such as August Pugin and others. Just as the folklorists attempted to reify the original text of ancestral populations, the emphasis of medieval revivalists, such as Thomas Carlyle’s reflections on medieval St. Edmunds monastery, served to rehabilitate a medieval society that had been disparaged by 18th century philosophes who regarded the medieval as primitive and unmodern. Pugin made the medieval attractive to his Victorian audience as he emphasised the relationship between its social milieu and its sacred architecture. And where did he do this? In the principal example of modernity, the Crystal Palace.

These efforts parallel what the folklorists did: namely “For this reason the texts underwent tremendous alterations, if not outright fabrication, by these scholars in order to make them suitable for their own purposes.” Ruskin’s interpretation in “The Nature of the Gothic” of medieval labourers working on Cathedrals in no way reflected their reality. Rather their narrative was entextualized, a “construction” of the medieval as a “science,” providing “evidence of traditional culture.” As Kerim quotes: “this entailed the wholesale fabrication of supposedly traditional folktales,” can be said of Ruskin’s fabrications of medieval labour and traditional society. In many ways these Victorian medievalists “played down the true hybridity” of the medieval from whom they drew their material.

How well does this fits with the folklorists notion of folklore as ” decayed remnants of a once great culture.” Pugin’s architectural books provide a narrative of ancestry for Victorians who can see through his writings an earlier great culture. Morris will write: “What is wrong, then, with us or the arts, since what was once accounted so glorious, is now deemed paltry?” Here is the beginnings of the movement of preservation and restoration of ancestral architecture (the scientific rehabilitation of the past to a pure form). Bauman and Biggs write: “This quest for the archaic and authentic related to form as well as content; Boas summarized his agenda as an attempt “to rescue the vanishing forms of speech”.” As such, Boas seems very much caught up in an historical period in which Victorian expertise was associated with valuation of ancestral forms (language, architecture, social customs).

It is amusing that when authors so concerned with historical influence and the ethnic origins of authors neglect a central fact about Boas, that he was born, raised, and educated in Germany and considered himself ethnically German.

According to Wikipedia,

Franz Boas was born in Minden, Westphalia. Although his grandparents were observant Jews, his parents embraced Enlightenment values, including their assimilation into modern German society. Boas’s parents were educated, well-to-do, and liberal; they did not like dogma of any kind. Due to this, Boas was granted the independence to think for himself and pursue his own interests. Early in life he displayed a penchant for both nature and natural sciences. Boas vocally opposed anti-Semitism and refused to convert to Christianity, but he did not identify himself as a Jew;[8] indeed, according to his biographer, “He was an ‘ethnic’ German, preserving and promoting German culture and values in America.”[9] In an autobiographical sketch, Boas wrote:

The background of my early thinking was a German home in which the ideals of the revolution of 1848 were a living force. My father, liberal, but not active in public affairs; my mother, idealistic, with a lively interest in public matters; the founder about 1854 of the kindergarten in my home town, devoted to science. My parents had broken through the shackles of dogma. My father had retained an emotional affection for the ceremonial of his parental home, without allowing it to influence his intellectual freedom.

The relationships are complex; but Boas thinking was far more likely to have been influenced by German Romantics than by British Victorians. And Germany was, after all, thanks to figures like Herder and the Grimm Brothers, the epicenter of 19th and early 20th century interest in folklore. Also of historicism and hermeneutics.

@John, You shouldn’t assume that just because I haven’t said something in two short blog posts synthesizing some key themes from a larger work that it is neglected in the original volume. Moreover, I think I have made clear in both posts that the book traces Boas’s intellectual heritage through Herder and the Grimm Brothers so the role of German Romanticism is actually a central aspect of their argument… If you were to just look up the table of contents you would see that these chapters take up two out of the book’s 7 central chapters (not counting the introduction and conclusion).

@Kerim. You are absolutely right. You did mention that Bauman and Briggs mention Herder and the Grimm brothers. But consider Fred’s remark, the one that immediately precedes my snark, in which we see Boas associated with “Victorian” thinking exemplified by three Brits, John Ruskin, William Morris, and Thomas Carlyle, with no mention whatsoever of Boas’ German roots. Is this a proper representation of anthropological tradition?

@John, I don’t think @Fred is trying to be “representative,” he is just making a very valid point about how Boas “seems very much caught up in an historical period in which Victorian expertise was associated with valuation of ancestral forms.” What is important about the book is how it teases out the nuances of this – what aspects Boas took from the Herderian tradition and what aspects he took from Locke and his colleagues – each of which has a very different view of the relationship between modernity and ancestral forms. It is a complex argument and I wrote these blog posts partially to try to understand it better for myself. Sorry if I didn’t make the points clearly enough, but if anyone is really interested in these questions I strongly recommend reading the whole book, or at least their chapter on Locke and Herder in the edited volume “Regimes of language” which summarizes their argument.

Sounds good. But for the sake of us for whom this book isn’t high on the stack of things we would like to read some day, saying a bit more about the Locke v Herder thing would not only be helpful. It could move the book higher on the stack.

@John, Sorry, that isn’t on my list, but I might write more about Boas’s theory of language… No promises though.

@Kerim

I am happy to report that with Kerim’s help I have located the Kindle edition of Bauman and Briggs Voices of Modernity. A rapid scan of the introduction and chapter 1 have already resulted in a much higher regard for the book itself than I had of the scarecrow version of it constructed from our conversation so far. I haven’t gotten to Herder yet, but what I have learned about Locke so far can be summarized as follows.

Locke was primarily concerned to separate the natural world as conceived by the mechanical sciences emerging in the work of Newton, Boyle, etc. from the social world. What, then, is the role of language? In contrast to Latour, who sees language as part of the social, Locke made it a “third province” in the tripartite scheme summarized at the end of the Essay Concerning Human Understanding.

For a man can employ his thoughts about nothing, but either, the contemplation of things themselves, for the discovery of truth; or about things in his own power, which are his own actions, for the attainment of his own ends; or the signs the mind makes use of both in the one and the other, and the right ordering of them, for its clearer information. All which three, viz things, as they are in themselves knowable; actions as they depend on us, in order to happiness; the right use of signs in order to knowledge. . . . seemed to me to be the three great provinces of the intellectual world, wholly separate and distinct one from the other.

This set of distinctions would, of course, justify the distinction between language and culture or society that justifies the division of linguistics from anthropology. But Bauman and Briggs’ concern is elsewhere. Because Locke also conceives of language that is properly well-defined and clear as a property of rational thought, where rationality is held to be the justification for scientific or political authority. In contrast, the language of the uneducated masses, which is ambiguous, unstable, shifty in its meanings, rhetorical rather than logical, disqualifies those masses, at home or in the colonies, from either scientific or political authority. Their voices can only be heard as irrational and thus should be ignored.

At this point I pause to observe that, while this distinction sounds ominous to those who believe that all voices should be heard and treated respectfully, it is, nonetheless, the premise on which the liberal left justifies contempt for those who deny scientific evidence for global warning or see faith in Biblical inerrancy as grounds for “creation science.” I offer for your consideration the thought that whether Boas was engaged in behavior that we, living in different times, find questionable is a less important issue than finding ways to engage in dialogue that is both respectful and critical, neither “You are wrong!” or “Whatever you say is right for you.”

Baumann and Briggs, Modern Voices. This book is an interesting combination of the very good, the bad and the ugly.

First, the very good. The meticulous unpacking of Locke and Herder’s views of language, the tracing of their historical relations to British antiquarianism exemplified by Aubrey and Blair, and the careful analysis of how these various views of language contributed to Boas’ thinking and anthropological practice are an intellectual historian’s delight. I learned a lot from reading this book and am very glad that I did.

Second, the bad. The recurring “critique” throughout the book is that the ideas under discussion turn language, either abstracted and universalised in Locke, or inextricably tied to “Der Volk,” an homogenous nationality whose descendants share blood and soil as well as language, into a support for racial, ethnic, class and gender inequalities.This is both true and one-sided. To follow its logic to the limit would lead, I observe, to a radical discounting of such other historical texts as The Declaration of Independence, the Constitution of the United States, and the UN Declaration of Universal Human Rights. More painfully, perhaps, for readers of Savage Minds, it would delegitimize “higher” education in all its forms. After all, all claims to academic expertise, in the humanities and social sciences as well as STEM and professional subjects, involve the use of prescribed forms of language to establish professional credibility. There may be those among us who are prepared to put the ravings of right-wing lunatics on a par with that of wishy-washy liberal professors. Personally, I am not prepared to go there.

Third, the ugly. The authors start their story with Bacon and Locke, making attempts to purify language and use purified language to justify social hierarchy seem a peculiarly modern thing. One has only to think of such historically familiar examples as Plato condemning sophistry and excluding poets from the Republic, Sanskrit grammarians, and recurring Confucian efforts throughout Chinese history to “rectify names,” to realize that language purification and associated claims to superiority are likely at least as old as writing. They may well go back farther than that, in the bards of oral traditions, whose performances use language in forms that are recognized as distinct from and superior to everyday speech.

The authors invite us to be upset that to present the Kwakiutl texts collected and annotated by George Hunt as “authentically Kwakiutl,” Boas passes over in silence Hunt’s status as a bilingual half-breed. Should we not be equally upset that, to support their notion of “modernity,” they ignore human history outside the usual Europe-centered tale of how modernity was created?