A favorite topic on the blogosphere is whether or not Seediq Bale is an historically accurate take on the Wushe Incident. Some details, at least, are inaccurate, and people have some questions for the director Wei Te-sheng. For instance: Why is Mona Rudao at events in the early 1900s he didn’t attend (人止關 in 1902 and 姊妹原 in 1903)? Why does Mona Rudao shoot at Seediq women when there’s no historical evidence for it and when it goes against gaya – tribal tradition or teaching? Where does the child warrior Pawan Nawi come from? And so forth.

In assessing Seediq Bale’s historical accuracy it’s helpful to distinguish between subjective and objective: between 1) immediate, indigenous perspectives on history as it unfolds as current event on the one hand, and 2) distantiated, contextualized interpretations of historians on the other hand.

At a promotional event I attended, the director Wei Te-sheng said he wanted the audience to forget everything that has happened since 1930. I take him to mean that he wants to transport us back in time and give us subjective perspectives, mostly indigenous perspectives, on the Wushe Incident. This subjective history includes a knowledge of tribal politics and more basically of the Seediq worldview, of Seediq belief.

First, what I’m calling “tribal politics,” with no disrespect or evaluation whatsoever intended in the use of the term “tribal.” It’s true that Mona Rudao and other indigenous characters in the film have a concept of the Japanese as an “alien race” or “foreign tribe.” Yet primarily Mona Rudao’s political world in the film remains one of territorial tribal alliances and antagonisms, involving in particular Toda and Tkdaya Seediq and to a lesser extent the Truku. Mona Rudao hates the Toda chief Temu Walis more than he hates the Japanese, and his hatred is more enduring.

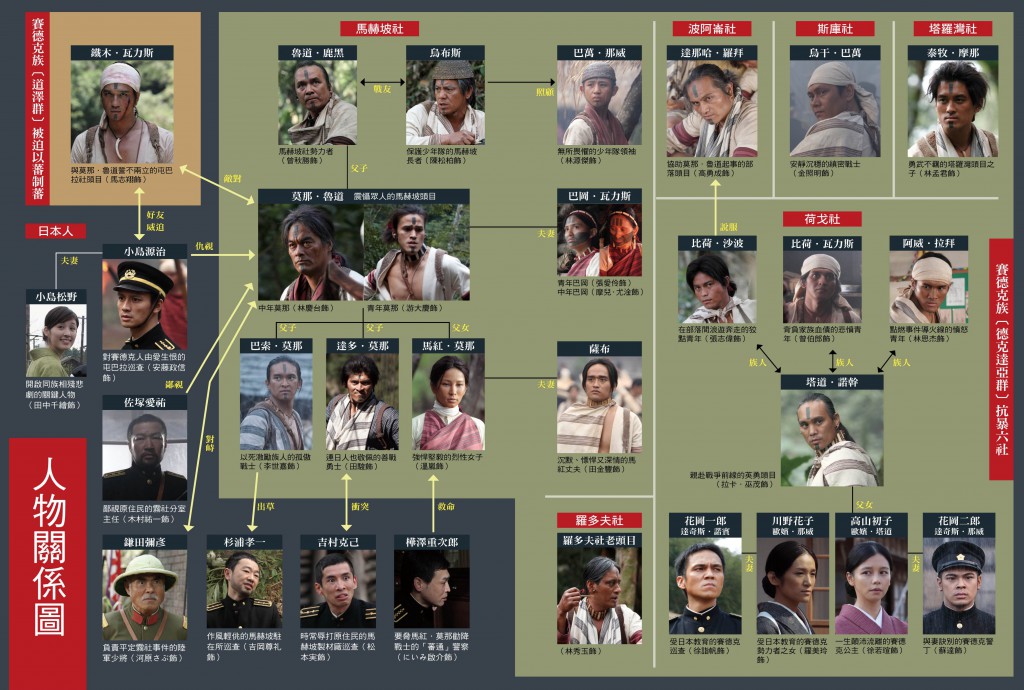

Would the film’s take on tribal politics satisfy a historian? A historian would probably be impressed without being able to accept the film as history. It seems to me that, the film’s alliances and antagonisms don’t shift. They kind of freeze. This makes it easier for the audience to understand. There’s even a poster for the benefit of the audience that lays out the different agents and their relations.

A historian would have a sense of an evolving not a static political system. More problematically, the film reduces the number of historical agents and simplifies their relationships in order to produce good drama. Too many characters and groups would confuse the audience, and make it harder to determine who to identify with. A film needs a hero, or at least a single or a couple of main characters to pay attention to. That’s why Wei Te-sheng put Mona Rudao at incidents he never attended (人止關 and 姊妹原), to keep him in the spotlight. He has to be in the spotlight, because he’s the main character in the main plot.

Main and supporting characters and main plots and sub plots are how we structure our works of narrative art and to some extent how we think about our lives. Historians can use these same tropes to produce narrative history, but historical narratives are always more complicated in history books than in novels or films. The narrative models a historian would build of the Wushe incident would regard individual motivations in the evolving system of tribal relations. People today don’t understand the system; they don’t have too much patience to learn about it. It’s much easier for Wei Te-sheng to present “interpersonal” relations not in the context of the system, but rather in terms of “love” and “hate.” In the film Mona Rudao hates the Toda leader Temu Walis. The audience gets it: Mona Rudao really doesn’t like the guy. The feeling becomes mutual, and that’s why Temu Walis agrees to go after Tkdaya warriors during the reprisal like a bounty hunter or a gun for hire. The actual relationship between the two men could not have been so simple. They went to Japan together several decades before 1930 (meaning that Temu Walis was not quite as young as he is portrayed in the film – see the promotional poster below)!

Second, the Seediq worldview. In his review of the film in the Taipei Times, Pastor Michael Stainton, who has worked with the Seediq people for decades, claims that the account of Seediq belief in the film is compelling. As Mona Rudao reminds us over and over again in the film, and as he was taught by his father, a seediq bale – a real man – has headhunted. If he arrives at the rainbow bridge of the afterlife with blood on his hands he can cross to the happy hunting ground on the other side. A woman can be a seediq bale as well, by mastering weaving and presenting her callused hands for inspection on this side of the rainbow bridge. Both men and women have the right to receive facial tattoos when they become seediq bale. (I should note that Professor Stainton and Professor Guo Pei-yi have both reminded me that the practice of gaya was more than just headhunting and weaving). In the film this seediq bale belief is presented as the most significant cause of the incident. Mona Rudao wants to give the young men of the tribe a chance to become Seediq bale by driving out the foreign race that has occupied and exploited the ancestral hunting ground. It is the desire to become a real man more than hatred of the Japanese that motivates the decision of each individual warriors. After all, in the happy hunting ground of the afterlife, the headhunters and their victims will be reunited as friends.

How compelling would this explanation be for a historian or an anthropologist? I’m not sure. It’s plausible. But where’s the evidence? Check out this picture of Mona Rudao:

Can you tell if he has scars? You sure can’t tell whether he believes in a rainbow bridge to the afterlife. I am ignorant, but if anyone promised to vouchsafe me certain knowledge on Mona’s motivations, I would have epistemological reservations. The only records we could have of Mona Rudao’s beliefs are from Japanese hands. We could interview very old Seediq people and ask them what they grew up believing or what Mona Rudao believed if they knew him, but their statements would be contaminated by the eight intervening decades. Japanese anthropological records would have to be used carefully. So a historian could consider the role of traditional belief in the incident, but would not be able to use belief to advance a certain explanation of the incident.

A historian’s lack of certainty or even ignorance about many things is the result of historical distance. No historian would write history about a current event. If he did he’d be a reporter. History can be written only with historical distance. This distance in theory allows for objectivity, but it also creates ignorance. When all you have is documents there will be many things you don’t know. Oral history can be problematic, our faith in the horse’s mouth notwithstanding. Historical distance must inspire a sense of humility. It might seem disappointing or embarrassing to admit that we just don’t know, but it’s the uncertainty, the room for discussion and provisional interpretation that makes history interesting.

Seediq Bale displays no such humility and narratively it’s kind of boring. The way Seediq Bale tells the story, everything is presented as truth, as how it happened not how it might have happened. In the first scene, Mona Rudao takes down a mountain boar. There is one major flashback in the film, when Mona Rudao remembers his father telling him about the Seediq worldview. Otherwise it’s just one damn thing after another. Sometimes there are twin narrative strands proceeding together in time; otherwise not much besides endurance is demanded of the audience. There is no objective perspective from a standpoint of historical distance.

By contrast, other literary adaptations of Wushe have begun in the present and reimagined the past. Dana Sakura, the miniseries about Wushe that played on public television in 2003, presented the frame story of a young Taiwanese man, a graduate student in history, who goes to Wushe and to the village of Qingliu, where the survivors of Wushe were moved in 1931, to try to understand the role of a relative in the incident. In A History of Pain Michael Berry sees this as a Taiwanese appropriation of the incident and that may be so. But it also introduces the historical distance of a frame story. That’s what frame stories do, create distance. The miniseries presents a reimagining of Wushe based on interviews the graduate student conducts. We get a sense of what it might have been like, of what might have happened. The same is true in the recent indigenous film Finding Sayun, which reimagines the story of Sayun’s Bell while reminding the audience: this might be how it happened. In another notable presentation of Wushe, Wuhe’s novel Remains of Life, which Professor Michael Berry is translating, all we have is the frame story; Wuhe refuses to reenact history in his imagination; his concern is the contemporary village of Qingliu.

Contemporary perspectives on Wushe are not necessarily objective. There’s a fuzzy boundary between subjective and objective. We try to be objective about the subjective. And being objective is really hard. Chinese and Taiwanese historians have interpreted Wushe according to their own worldviews, and in some sense it’s impossible not to, as we always write from a limited perspective; that’s what Gadamer was on about with the fusion of horizons (though alas it’s so often the confusion of horizons). I don’t think contemporary indigenous ideas about Wushe are necessarily more objective. Indigenous peoples have historical distance but might not like the humility that has to go along with it. At the same time, indigenous people’s views deserve special respect. It’s more their history than anyone else’s. I’ll try to critically discuss three indigenous perspectives on Seediq Bale in the context of my discussion of subjective and objective history in Seediq Bale.

Indigenous Perspectives on Seediq Bale

First, Seediq people argue that Mona Rudao would never have shot at his womenfolk because it goes against Gaya. I’m a bit skeptical. What Gaya was in 1930 was not written in stone. From my limited experience reading Taiwan aboriginal fiction, people are not always in agreement about what their tradition is. In Rimui Aki 里慕伊.阿紀’s stories, for instance, women don’t always agree with male interpretations of Gaya. Also, even if Mona’s act was against Gaya, the relationship between social rules and contact is complicated. People in Taiwan joke about how a red traffic light is for reference purposes only when they don’t want to wait for the light to change. People take the rules into consideration, but as Bourdieu argued behavior is constrained not determined by rules. What’s more objectionable about the scene in question is, again, that we don’t know whether it happened, and Wei Te-sheng presents it as if it actually did happen.

Second, in the aftermath of Wushe, the Japanese paid Toda warriors to slaughter the Tkdaya rebels. This is historical fact. I’ve already noted that the fact has to be understood in the context of intertribal relations not in terms of interpersonal animosity. Also, there are still Toda and Tkdaya people alive today and some of them are not pleased that the historical conflict between them has been dragged out and displayed in the light of day. I know where they’re coming from. But I don’t think that the Toda leader Temu Walis is portrayed negatively in the film. He’s played by the heartthrob actor Ma Zhixiang (Umin Boya). Umin Boya is himself a Toda Seediq. He’s one of the most interesting characters in the film; he’s very tormented by the fact that his traditional belief has been commodified by the Japanese. He’s not presented as an evil character.

Third, a related matter is the presentation of the “hero” of the film, Mona Rudao. In Seediq Bale he’s, well, heroic. He conceives an irrational hatred of Temu Walis, but heroes don’t have to be nice according to some small minded concept of how people should behave. In the film Mona Rudao is larger than life. But not all contemporary Seediq see him that way. The Toda especially have their own views of chief Mona, and not all of them are positive. Not all of them are all that heroic, either. Hero-worship does not make for a good historian, because heroes belong in myths and legends not in history. Individual achievements may seem heroic, but the glory fades when you understand them in context. Mona Rudao was taken on a tour of Japan. He remained chief for so long because he had Japanese support, because he was a pawn in a complicated field of power. The Toda historian Kumu Tapas has, by compiling oral history, been gathering materials by which a more balanced picture of Mona Rudao might emerge.

For eighty years, Wushe has been represented from Japanese, Chinese and Taiwanese perspectives. Now that indigenous people have started expressing their own perspectives, non-indigenous writers, filmmakers, or novelists have to be more careful. They can’t just make things up. And hopefully someday soon, we will have an indigenous fictional narrative version of the Wushe Incident.

Great review. Amazed at the level of detailed historical and anthropological analysis in this article, it far surpasses most articles written in Traditional Chinese.

One thing though, I have read some Japanese accounts that quoted recountings of Mona Rudao shooting his family before he himself sought death in a remote place. Whether this is the true, who knows, but at least it isn’t something that Wei made up out of thin air, and there is certainly no need to make this kind of plot up. Wei in the end tried to satisfy both the historical records and the present day Tqdaya “it is against gaya hence it didn’t happen” argument by fading black at the gun shot, and then having the wife’s body removed from hanging on trees to satisfy gaya.

I think the film is certainly not perfect historically, but I understand why Mona was put in 1900s conflicts to focus the story a little. There are other numerous times Mona plotted revolt and was upset by the Japanese. One of his plot was revealed to the Japanese by no other than Temu Walis or at least his Toda tribesmen. Those are omitted for time. Over all, for the restraints that Wei has to fight against, I think it is told in a satisfying way.

I also think Mona’s story was already over by the first film. The rest was about his family, the Hanaokas and Temu Walis.

It is sad that even with this films perspective, many people still want to judge the characters as good or bad, and their actions as right or wrong. I thought this film is about people after being deprived of tradition, faith and livelihood, sought the only action they know to preserve life or dignity from all parties.

Gone with the historical Japanese perspective of blood thirsty savages, gone with the historical Chinese perspective of brave Chinese brethren fighting the evil Japanese colonials, gone with the tribal politics perspective of collaborators, or the old fool who disregards life to satisfy his own dignity. And let the audience put themselves in that era. And I think it did a darn good job of that.

Thanks Hansioux!

For everything critical I say about the film, and I think it deserves a critical response, I thought it was a great film, very effective, and I liked it better the second time I saw it. The reverse was true with Avatar.

Thanks also for noting the Japanese account. There’s an immense amount of material on Wushe, and I am in no way an expert on the history. I’m merely a litcrit or film studies commentator. I address historical issues in this post, but, because I’m not a historian, tend towards the theoretical.

Yours,

Darryl.

Was the Burmese Harp by Kin Ichikawa an accurate portrayal of the Japanese troops in Burma? Likely the film was not… directors take poetic license to create protagonist that face difficulties to overcome…I don’t think Odysseus heard ‘sirens softly singing’. He,too, larger than life overcame greater obstacles than were possible all for a woman. The hero’s journey has been portrayed many ways. I enjoyed the film; none are pefect but many are four and five stars. In film school they taught us it is hard to make even a ‘bad film’.

Wow! What an interesting read! I’ve only seen the movie just now and knew nothing about the Wushe incident beforehand but have been reading up on it since and am appaled at how bad mankind can act. I live in Australia and the Indigenous Aborigines here faced similar oppression.

Do you know if the Japanese are remoreseful of their actions? and it’d be interesting to know the relationship between Japan and Taiwan nowadays.

I’m studying at uni at the moment but nothing to do with film or history but this is very interesting and sad also to know that indigenous people from other parts of the world have been ‘civilised’ by people who think they are savages and caused so much death and loss of their culture. I sometimes think the world would be better off living thee way indieginous people do off the land, respecting the land and not worried about money or wealth but just living.

thanks for the good read!

Just saw the movie. It was amazing. like comments above I have never heard of he Wushe incident. At the web site for the movie, the story page idicated the suvirvors of the Sadeeq were eventually relocated to an island off Taiwan. Can anyone verify this and if so, where is this island.

thanks,

Phillip

Saudi Arabia

@Phillip

This is what it says on the film’s website:

“The Japanese soon exacted their revenge. They first mounted ‘The Second Wushe Incident’: the execution of more than 200 captured rebels, designed to deter any further uprisings. They then moved all surviving Seediq tribespeople to an offshore island (they named it Kawanaka-hara-jima) connected to the mainland only by a flimsy suspension bridge. The Seediqs were finally isolated and contained.”

However, I think this is a mistake. The 川中島 (as I believe Kawanaka-hara-jima is written) is actually in a mountain valley, even though the last character does mean “island.” I don’t know where they got the part about it being “connected to the mainland only by a flimsy suspension bridge.” You can see some pictures of the villages that are there now on this blog post:

http://goo.gl/eMGy9