The epic film Seediq Bale: Warriors of the Rainbow Bridge is of particular interest to translators because it’s in the Taiwanese aboriginal language Seediq. As a Chinese-English literary translator I’m naturally interested in problems of translation in the film. Unfortunately, I don’t know the Seediq language. Translators know they should comment on languages they know well; but I’m going to go out on a limb here and comment on one issue of translation in Seediq Bale: the title of the film. Then I’ll use the nativization-foreignization continuum from translation theory to comment on different translations of the title.

The screenplay of Seediq Bale was translated into Seediq. Eleven years ago, the director Wei Te-sheng won an award for the screenplay:

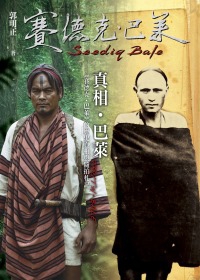

The original Chinese language screenplay was translated was translated into Seediq by Dakis Pawan (Guo Mingzheng).The same kind of situation applies to films like Dances With Wolves and Apocalypto where a director of a dominant language – in both these cases English – wants to present the illusion of linguistic authenticity by having part or all of the screenplay translated into an indigenous language. Guo Mingzheng is a Tkdaya Seediq, belonging to the same group as Mona Rudao, the hero of the film; he has written a Chinese language book about his experience as translator and adviser to the director.

There are two basic ways to consider what Seediq Bale means: in Seediq and in foreign languages like Chinese or English.

There’s a lot to say about what seediq bale means in Seediq. Seediq is what anthropologists call an endonym; it’s a designation the Seediq applied to themselves. It means, “we, the Seediq people.” Traditionally it did not cover all humanity, as does the term “people.” Bale means real or true. It also means “authentically local.” Sama bale means “authentic, local vegetables.” Rodux bale means locally raised chicken. Bnga bale means locally grown yams. The scholar I discussed the meaning of Seediq bale with, Iwan Pering 伊婉.貝林, provided the following notes on what a seediq bale is:

- An insider, someone belonging to the group. Seediq bale is boundary between in group and out group.

-

A local person, born and bred.

3. Headhunting was not the whole of the meaning of Seediq bale, but if a man headhunted while defended his territory he would automatically be considered a Seediq bale.

4. A person who follows Gaya is a Seediq bale. Gaya is the ancestral teachings, the social norms, the ritual practices, the “laws of life” (Stainton), the “moral tradition” (Guo Peiyi) which maintains the relationship between man and cosmos. That’s something that is said of someone with the highest ethical standards. This is an ideal towards which Seediq people aspire and may only achieve in old age, which is why young people learn from their elders.

In mythology, when a Seediq person dies, he or she must walk over the rainbow bridge, but guarding the bridge is a crab spirit (Utux karan) who will inspect to see whether men and women have red marks on their hands, indicating that they were able to protect their families as men and clothe their families as women. People who can cross the bridge are Seediq bale.

Now I want to consider different ways of translating seediq bale into Chinese or English.

In Chinese there are two translations of seediq bale, one a Chinese transliteration: 賽德克巴萊 sai-de-ke ba-lai. People in Taiwan are familiar with sai-de-ke (Seediq); they just have to learn “ba-lai” or bale. The other translation explains what “ba-lai” means: 真正的人 zhen-zheng-de-ren, or true/real person. To my ear, zhenzheng de ren has a strange, slightly off quality. zhen-ren 真人 is better, or less odd sounding, but then it’s not exactly common parlance. It means a Daoist master, someone who has achieved the way or the son of heaven. In English, I think “real person” and Prof. Stainton’s suggestion of “true human” both sound odd. I’m responding as a translator; to me, these translations seem literal, as if something’s been lost in translation. In both English and Chinese people say “a real man” (真正的男人) or “a good person” (好人) or “a good man,” but not “a real person” (真正的人). That’s not to say that zhenzheng de ren or “real person” are meaningless. They kind of make sense, or one can try to make sense of them. But they’re odd. If you’re a Chinese person, try casually slipping it into conversation, and not in reference to the film Seediq Bale. It’s not easy to do. It’s even harder to do this with “true human.”

The strange, slightly off quality of literal translations is part of a translation strategy called foreignization. A foreignized translation is not a bad translation or a mistranslation. A foreignized translation tries to draw the reader towards an alien culture, to get the reader to understand a strange culture on its own terms. A nativized translation, on the other hand, draws a concept in a foreign linguistic culture towards the reader, normalizing it. My own preference as a translator is for a foreignized translation; as a translator, I find foreign linguistic cultures fascinating and want to share my fascination with the reader. I originally assumed that seediq bale might simply mean “adult” or 成人, that this might be a nativized translation of the term. That’s not the case. Seediq bale is not one of the stages in the regular progression of life: infant (rabu), child (laqi), a young person who has come of age (riso), and an elder (rudan or baki). Seediq bale is an objective of fulfillment of the whole person, a concept with a spiritual, religious or philosophical meaning. Prof. Pei-yi Guo (in the comment below) suggests “ideal person,” which sounds like a term from abstract philosophical discourse to me, and would also not make a good title for a movie. “Seediq hero” (賽德克英雄) would be a nativized translation, familiarizing a foreign concept, and indeed in the short promotional film Wei Te-sheng made in 2003 to raise money for Seediq Bale he uses the term hero. In the English poster for the film, the problem of what seediq bale means is avoided entirely: Seediq Bale: Warriors of the Rainbow, implying that seediq bale means “warriors of the rainbow.” When Wei Te-sheng had the chance to go back to Seediq Bale he opted for the more literal, foreignizing translation of zhenzheng de ren or “real person.” But whether a foreignizing translation is effective depends on the reader, who has to do the work of understanding. Wei Te-sheng does not provide the kind of detailed analysis a person would need for a “true understanding,” and it seems to me that most people will come away from Seediq Bale with a romantic image of what a seediq bale is: Mona Rudao on the mountaintop, shot from below.

A dose of linguistic reality is therefore in order. Seediq is now spoken by a few thousand people. I’ve read that the excitement of Seediq Bale has gotten people interested in learning Seediq. This is heartening. But learning a language is a long haul. Despite Seediq Bale it’s not likely to be spoken by as many people fifty years hence. We need linguistic Seediq bale, heroes and heroines of the Seediq language, but there aren’t too many of those around and don’t expect an epic film about one anytime soon. Linguistic seediq bale are people who prefer foreignized translations, who try to think things anew through a sustained encounter with the linguistic other. Taking a class isn’t enough to do that, much less going to see a movie. Few can see the glory in becoming a linguistic seediq bale, including I imagine Wei Te-sheng himself. If he had he would have learned Seediq instead writing a Chinese language screenplay about the Wushe incident and turning it into a movie. But in making the movie he has offered us the opportunity to remind ourselves of the imperiled state of Seediq and Taiwan’s aboriginal languages in general.

NOTE: as this blog post seems to be the only treatment of the issue in English, I’ve rewritten it after consultation with a native speaker and after receiving Guo Pei-yi’s feedback below. It just goes to show that when you go out on a limb sometimes the limb breaks. Having written and revised this blog post I feel anew the need to begin learning one of Taiwan’s aboriginal languages. I have not fully explained the issue of tattooing and will do so when I sort that out.

Again, many thanks, Darryl, for an extremely thoughtful and informative post. It may interest you to know that the name the great majority of indigenous people all over the world give themselves is in fact their own word for “people,” with the implication “real people” or perhaps better “authentic people.” I don’t see this as snobbishness, however, or a form of xenophobia, but more simply, and more interestingly, an archaic tradition.

This is purely conjecture on my part, but as I see it, our early human ancestors would have found it important to distinguish themselves from other animals and would have wanted to invent a name for themselves that did the job. So they would have called themselves by that name, i.e., “people” as opposed to animals. This naming practice would have become established as a tradition and was thus handed down over the generations, as the original lineage split into many thousands of subgroups and spread all over the world.

> it wouldn’t be wrong to argue that Seediq bale means “adult” or “Seediq adult.”

I have a different reading. I don’t think the meaning of ‘Seediq Bale’ is equal to ‘adult’. What is involved is the concept of personhood (sort of fundamental in anthropological theories). The meaning is closer to ‘ideal person’ instead of adult. The Seediq believed that one could reunite with the ancestors only through the path of the rainbow. The practice of gaya (moral tradition) qualified a person to walk across the rainbow; the achievements of headhunting (male) and master weaving (female) were only partial fulfillment of gaya. It is a central message of the film.

As for the title. I think there is a contexual difference that you have not taken into account: Seediq is a meaningful word in Taiwan, since it’s the name of an indigenous ethnic group. Therefore the Taiwan title Sai-de-ke-ba-lai (following the pronunciation of Seediq Bale) makes sense to the audience. They only need to learn a short new word ‘bale’.

Thanks again Victor, your theory sounds plausible. I would imagine that the meanings of these endonyms might change when they come into contact with other people. A specific people might have to generalize the term. It used to just refer to us in distinction to animals, but now it refers to humans in general in distinction to animals. Or they would introduce a new, more general term, retaining the other term for themselves.

I’m reminded of something my linguistics teacher told me about the word for fish in one of the Salishan languages. He said there wasn’t a word for “fish.” There were words for different fish, and eventually they decided to use the word for salmon as a general term for fish in general.