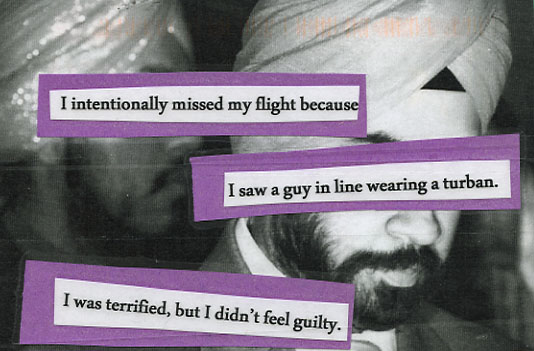

Via the PostSecret website, it is unclear whether the poster intentionally picked a photo of Sikhs or if this was unintentional irony. Not that the sentiment would have been any less offensive if the person wearing a turban was actually a Muslim. It certainly didn’t matter to the families of victims of post 9-11 hate crimes whether the victim was Muslim or not. I bring this up because William Dalrymple has an op-ed in the NY Times about the proposed Islamic center planned for lower Manhattan (for those living under a rock, see William Saletan’s piece in Slate for a good roundup of the issues surrounding the center):

The problem with such claims goes far beyond the fate of a mosque in downtown Manhattan. They show a dangerously inadequate understanding of the many divisions, complexities and nuances within the Islamic world — a failure that hugely hampers Western efforts to fight violent Islamic extremism and to reconcile Americans with peaceful adherents of the world’s second-largest religion. Most of us are perfectly capable of making distinctions within the Christian world. The fact that someone is a Boston Roman Catholic doesn’t mean he’s in league with Irish Republican Army bomb makers, just as not all Orthodox Christians have ties to Serbian war criminals or Southern Baptists to the murderers of abortion doctors. Yet many of our leaders have a tendency to see the Islamic world as a single, terrifying monolith.

Dalrymple’s main point is that the Sufis behind the Cordoba Initiative are themselves “infidel-loving, grave-worshiping apostate[s]” in the eyes of the Taliban and Osama bin Laden. We’ve been here before:

In 2006, the investigative reporter Jeff Stein concluded a series of interviews with senior US counterterrorism officials by asking the same simple question: “Do you know the difference between a Sunni and a Shia?” He was startled by the responses. “One’s in one location, another’s in another location,” said Congressman Terry Everett, a member of the House intelligence committee, before conceding: “No, to be honest with you, I don’t know.” When Stein asked Congressman Silvestre Reyes, chair of the House intelligence committee, whether al-Qaeda was Sunni or Shia, he answered: “Predominantly – probably Shia.”

Clearly the United States would be better off if our leaders, journalists, and citizens knew a little more about Islam. But there are also some lessons here about the semiotics of racism which I would like to think offer some insights beyond the 24 hour news cycle.

A Liverpool working-class accent will strike a Chicagoan primarily as being British, a Glaswegian as being English, an English southerner as being northern, an English northerner as being Liverpudlian, and a Liverpudlian as being working class. The closer we get to home, the more refined are our perceptions.

The above quote is taken from a discussion in Asif Agha’s masterful book Language and Social Relations. Agha’s focus here is on the limits of of performativity. By pointing out that the hearer’s own prior socialization provides an important context for the successful performance of identity, Agha sets the stage for one of the book’s central themes: that identity is not only mediated by discourse, but also requires a process of negotiation between speaker and hearer—and that this process of negotiation can be transformative, changing the possible range of identity positions available to both parties as well as society at large.

I quite like Agha’s argument, and in chapter after chapter he makes a convincing case for it. Particularly interesting is his discussion of kinship terms, in which he shows how a mother might refer to her in-laws using terms which, taken literally, would place her in the role of her own child vis-a-vis her relatives, but are nonetheless lexically differentiated from the terms a child might use. In doing so she claims her rights as the mother of the child without reducing herself to the status of a child.

While the discussion of a Liverpool working-class accent shows that Agha is aware of the limits to such performativity, I would have liked to see more discussion about situations where one party refuses to negotiate. Agha’s approach to limits implies that performativity might fail because of one party’s lack of socialization, but what about if one party has a will to ignorance? I think such willful ignorance is behind much American confusion with regard to Muslims, and so I’m not sure how much use historical, ethnographic, or journalistic accounts of the various divisions within Islam can help.

It seems to me that part of the problem derives from the very idea of a “just war.” As Judith Butler argues, such a concept requires the “division of the globe into grievable and ungrievable lives from the perspective of those who wage war.” For some section of humanity to remain “ungrievable” requires a willful ignorance which refuses to engage in the kind of dialog which would allow for negotiated meanings to emerge. Thus, Islamophobia is in some ways a prerequisite for waging a global war on Terror, even as our leaders insist otherwise.

Kerim, great post. I wonder, though, if “will to ignorance” isn’t itself an oversimplification of what is going on when people refuse to negotiate a new understanding of the other. I see a range of possibilities, from cynical demonizing in political discourse to the outcome of deep socialization that makes some categories so fundamental to a world view that they are very hard to change, plus, of course, interactions where one meets the other.

There is also the possibility that the willfulness in question is a function of real interests at stake. I think both of classic murder mystery plots, i.e., those which turn on the presence of a stranger who claims to be the missing heir to the estate, and a Cornell industrial-and-labor-relations professor who pointed out to the innocent I was in high school that sometimes the parties to a dispute know perfectly well what the other is saying but also recognize that their interests are irreconcilable.

Anyway, thanks for the pointer to what looks like a really interesting book.

I’m glad to see about post about this issue here at SM. Especially after reading through a lot of the news media coverage of this issue. It amazes me how entrenched certain categories can be (as John already mentioned). Much of the coverage speaks of “Muslims” as if they are in fact one large group that acts and thinks the same–there is no attention to historical or political differences and details. And maybe (again, as John mentions) some of this is intentional.

“Thus, Islamophobia is in some ways a prerequisite for waging a global war on Terror, even as our leaders insist otherwise.”

Well, it certainly keeps the level of fear and paranoia up, doesn’t it?

Thanks for this post.

While in Burkina Faso this summer I often wore the keffiyeh my girlfriend found for me during a trip to the Grand Marché. (If you ever wear a keffiyeh for one day in a way hot, way dusty locale you will never again be parted from it.) The Burkinabé got a real kick out of the site of me—while waiting on the side of the road one evening following a fender bender our bus was involved in a group of school-aged boys kept staring at me and asking each other «Est-il un Arabe?» and the crusty old member of the Police Nationale who was checking passports at the entrance to Ougadougou Airport smiled and called me «Hajji» when he handed mine back to me. Literally minutes afterwards I was in a shuttle full of Europeans many of whom were clearly unnerved by my presence. The juxtaposition was a little breakneck even for me.

McCreey makes a good point :the parties to a dispute know perfectly well what the other is saying but also recognize that their interests are irreconcilable. At this time of gearing up for political elections in the U.S., it seems everything is a political football, and both the Democrats and the GOP are at logger-heads regarding distinguishing themselves from each other. A shift in the House is at stake, and any incentive to get voters off the couch and vote may allow either party to control the House and set the agenda over the next two years. In this case, it’s not just a will to ignorance, but something more like Braudillard’s notion of simulacrum. Image has taken over, and the notion of a mosque near the Trade Centre is a terrific visual point (voters don’t even have to have a real image, they can imagine it) over which the GOP can distinguish themselves in the upcoming election. Not to say that this sort of “ignorance” will not continue. Wouldn’t one solution be for politicians to go out and meet their muslim constituents.

One final point, racial profiling in Arizona applied to enforce immigration laws also raises the same issue of preception you identify in Asif Agha’s book. It seems the Arizona laws are a willful breaking down of negotiation, and the reduction of identity on both sides: American versus illegal immigrant. What happens to performativity from the legal perspective in terms of those arresting individuals, the courts and other branches of the immigration services? Liberally borrowing form Butler’s notion of just/unjust war, immigration can be seen in just such a perspective. The illegal individual becomes the “ungrievable” and, thus, the dialogue becomes monologic.

What does anyone think about the idea that willed ignorance is a cultural trait of certain Anglo American classes and tradtions and sub-cultures that has a very long history? I think it is a persistent literary theme at very least. Everything from the British upper classes of yore pretending the servants in the room can’t hear by slightly lowering the voice, to the Pilgrims pretending they are going to repay the theft of many bushels of corn on Cape Cod in 1620, to the Great Gatsby, to Laura Ingles Wilders dad pretending that the little house land will be legally his even though he is on Indian land, to people you maintain the civil war was not about slavery but about states right to have slavery, modern GOP pretending that keeping the Bush taxcuts will not put us in debt. I think willed ignorance is a very real thing.

Erik, what I think is that you have cited a number of examples in which people in power had serious stakes in maintaining certain fictions. These deserve careful analysis. Lumping them together as “willful ignorance” and calling that a “cultural trait” is only pejorative labeling. It adds nothing substantial to understanding the practices and situations in quesiton.

I’m still trying to figure out if “sometimes the parties to a dispute know perfectly well what the other is saying but also recognize that their interests are irreconcilable” is simply another way of saying “will to ignorance” or if it is helpful to distinguish situations where the hearer is ignorant from situations where the hearer is only acting ignorant. Clearly, in the particular case under discussion it is easy to show the hypocrisy of political players who have taken different positions when it suited them. (e.g. Jon Stewart showed clips of the “radical imam” as a guest on Fox news.) Yet in order for their claims to be effective, there has to be a kind of willed forgetfulness on the part of their interlocutors, so I am not sure if worrying about what the speakers know or didn’t know changes anything?

Kerim, you wrote identity is not only mediated by discourse, but also requires a process of negotiation between speaker and hearer. It might help to reposition this notion of identity within the frame of aesthetics–viz, how is a work of art created by those looking at it? The notion of aesthetics raises the issue of a multiple or complex set of facets which go to make up the aesthetic experience, and which resultant interpretations viewers transfer to the object or performance (say in a drama). The idea of “identity” in aesthetics becomes something appended to the object by the viewer, and each viewer appends a different sense of aesthetic identity. Often there is conscensus, and intrusion of political conscensus, as simply as placing a painting in a section of a museum and labelling it “nineteenth century impressionism,” or “Islamic minature.” Generally, we tend not to speak of there being a “negotiation” between the viewer and the object, but in many ways there is, and much depends on encoding within the work that has to be recognized by the observer. “Willful ignorance” would invovle either (i) inability to recognize the code, or substituting alternate codings, imposing an alternate matrix of signals upon the work, or (ii) refusing to read the code except in the most elementary manner (just observing its colour scheme or shapes).

This would begin to address McCreery’s point that “willful ignorance” may be an oversimplification, and rather we should unpackage such a term in the way negotation operates or fails to operate. My point above also suggests that “identity” is also an oversimplification, and that recognition of identity is not all that is going on in such negotiations–it is not simply the recognition of an “I” as opposed to an “it”, but a deeper sense of individuality as presented at a moment in time (if you will, a more phenomenological perception of individuality which requires both parties). I hope my little analogy of aesthetics offers some insight.

Fred, very nice. A simpler reply might be to point to the difference between “I don’t want to know” (I’d call that willful ignorance) and “I know but I won’t acknowledge that I know (I’d call that deceit).

Fred,

Agha and other semioticians like to talk about the “materiality of the sign,” emphasizing the life that the sign has beyond its initial utterance. Your examples from the art world are very apropos of this. In fact, there is a very good post on Slate about the Islamic aesthetics embodied in the Twin Towers:

http://www.slate.com/id/2060207/pagenum/all/

However, I’m still not sure that I find your distinction between “inability to recognize the code” and “refusing to read the code” that useful. First of all, aren’t I already making such a distinction in my post?

“While the discussion of a Liverpool working-class accent shows that Agha is aware of the limits to such performativity, I would have liked to see more discussion about situations where one party refuses to negotiate.”

I’m not sure what your and John’s rephrasings add that I haven’t already said? It seems to me that you wish to somehow further subdivide the second case into one which also includes the former?

My second problem is that I see “refusal to negotiate” as focusing on observable human action. While I acknowledge that “willful ignorance” introduces an element of intentionality, I don’t want to place too much emphasis on the question of intentionality, which has a problematic history in semiotic theory. At the risk of undermining my own argument, let me explain by asking a series of questions:

First, how can we tell? It is honestly difficult to tell if politicians and media personalities are just stupid or venial. Which is Sarah Palin?

Second, are these two really that distinct? My point with the concept of willful ignorance is that there is a second step involved which you are missing. Specific knowledge about, say Sunni vs. Shiite may be genuine ignorance, but this ignorance stems from an earlier will to ignore information about people different from ourselves.

Third, how do you know what you don’t know? To what extent is it possible to attribute intentionality to people who might be unaware of their own ignorance? See my earlier post on the Dunning-Kruger effect:

/2010/06/25/the-dunning-kruger-effect/

Forth, to what extent is intentionality important when we are talking about the materiality of the sign? See, for instance, Derrida’s debate with Austin about this. (Similar to your point about aesthetics.)

As I hinted above, these problems raise questions about any semiotic theory based on intentionality, including the concept of “willful ignorance” which I argue for in my post. However, I’d like to think that in the phrase “refusal to negotiate” we can find a basis for defining the term which is grounded in human action and discourse, and which does not require a theory of intentionality. To put it another way, the difference between someone who is ignorant and venial is in their subsequent behavior. The ignorant person will be receptive to new information, the venial will not. My criticism of Dalrymple is that he assumes ignorance is the problem.

If the claim is that the (formerly) ignorant will be distinguishable via a sea change in behavior I have to disagree. It is possible that an individual whose primary commitment is goal-oriented and/or ideological will just dig in his/her heels all the more after exposure to the new information (cf. Russ Bernard’s educational model of social change). As Goebbels said of the leadership style of Churchill and his cohort, “[It] depends on a remarkably stupid thick-headedness. The English follow the principle that when one lies, one should lie big, and stick to it. They keep up their lies, even at the risk of looking ridiculous.”

I guess I am trying to say is that I do tend to accept that the truth sets us free. For some of us that means ‘freer to deceive.’ One’s mileage may vary, as always.

Thanks to both John McCreery for the “nice,” and Kerim for the long response (a long reply deserves a thoughtful response). Your questions raise many points, most of which take me beyond my understanding of socio-linguistics, and the best I can hope to do is respond in a more or less impressionistic manner.

Let me begin with the question of “intentionality.” My own conception of intentionality revolves around a distinction between “intention” and “agent” (or “agency”). Using the Freudian idea of paraphrasis (slips of the tongue), I can say that “I” am the agent of any such slip, but it escapes my “intention.” From what I understand of the Derrida-Austin debate, intentionality need not correspond to an inner-mental act. Intention could be rescued if we could correspond say an observation of an act by the hearer and what they say, but this would be a special case. What I am trying to avoid is reducing “intention” only to an unconscious act, much as slips of the tongue.

Where we might hold someone such as Sarah Palin to account is as an agent. Agency regulates the interpretation of intention by others. Thus, if Palin is being venial, the question may be put to her as an interpretation of her actions. How she then denies, emends, accentuates, and deflects such an interpretation indicates how she regulates such an interpretation of her “ignornance.” Thankfully, we live in a world of Twitter, so that the accumulation of tweets allows investigation of just such a question in regard to politicians.

Alternatively, if I were to follow a Derridian tract, I might conclude that “intention” is in part a task of language itself, that language conveys intention apart from the speaker. In such a way, I could avoid localizing intention as somewhere between an inner mental-act and the unconscious: we could redeem intention within the frame of the conversation. I am not sure whether this is an approach which might salvage “intention,” as you say in the materiality of the sign, but I hope I am inching my way towards something at least half intelligible.

While I have no response to your second point, I have a a liminal idea concerning the third: how do you know what you don’t know? Certainly, I know that I don’t know anything about Quantum Mechanics, but to say this is to say I know there exists a body of knowledge about which I have no knowledge. Howoever, so much else of life depends not upon well-defined knowledge, but upon knowledge related to everyday interaction. Most phatic phrases, such as “How are you,” “Good-day,” and others, have little meaning except as lubricants to interaction on a daily basis. Clearly, I may not want to know how “you” are, and I could easily have replaced the above with “Hey.” At such a level, our knowledge of these phrases is more intuitive, often reactionary to settings, stimuli and such. The problem as I see it is when knowledge of the difference between Sunni and Shia becomes mistaken for this sort of intuitive, reactionary knowledge.

In many ways, television has contextualized our responses to the distinction between Sunni-Shia by providing intutitive understanding, usually in visual form. We are not interested in identfying the distinction between Sunni and Shia, but we are interested in how we represent expressions of such to one another. How the question of willful ignorance fits into this is still something of which I am not entirely sure. I agree, the question of how does one know what one does not know is a vexing question, I believe one going back to Socrates, but I feel part of the paradox lies in the nature of “knowing” rather than in what is known.

By way of replying to both @MTBradley and @Fred’s thoughtful posts, I think we can distinguish between:

1. Ignorance, but a commitment to knowledge

2. Either genuine or feigned ignorance, with a commitment to ignorance.

While we can’t distinguish between genuine and feigned ignorance in the second case, I’m not sure it matters. My point (at the risk of sounding too Parsonian) is that it is the ideological commitment to knowledge or ignorance which is important, not the mere fact of ignorance.

See this post, which argues that “There’s some history to people telling pollsters that they believe intensely negative, unsupported things about a president they hate.”

Thus people believe Obama is a Muslim because they put both Obama and Muslims in the category of “things they hate.” Like any racists, these people will probably admit that not all Muslims are bad, and maybe they even have some friends that are Muslim, but as @lavika recently said on Twitter: “it’s not the info that monocultural America doesn’t get…it’s the entire premise of multiculturalism/pluralism.”

“Agha’s approach to limits implies that performativity might fail because of one party’s lack of socialization, but what about if one party has a will to ignorance? I think such willful ignorance is behind much American confusion with regard to Muslims, and so I’m not sure how much use historical, ethnographic, or journalistic accounts of the various divisions within Islam can help.”

People like their narratives/normative systems etc. stable and simple. A sense of “aesthetics” is the sense of balance and order generated in the subject’s own imagination. “We were attacked” is simpler than knowing the history of the interrelations of East and West, Colonialism, European anti-semitism, Israel, Mossadegh and and Saudi Aramco. And people socialized to normative America have little interest in question what others might call American exceptionalism. Hardhats’ chest-thumping and Liberal assumptions if the US role in the world are gradations or varieties of the same logic. Zionists also demonstrate a “willed ignorance” of Palestinians, men of women, heterosexuals of homosexuals and on. As I’ve said more than once, experts on cars and highways are not the ones to ask for information on public transit and high speed rail. Not only will they not have the relevant information, they won’t be socialized to the discussion. In all cases, aesthetics and sensibility come first.

But then willed ignorance can be also an explicit and a moral choice: the refusal to accept the terms of relations imposed by another group. That’s the opposite of an avoidance of responsibility. But that dis-engagement/de-socialization has its own problems since left to itself as a moral aesthetic it’s destructive of community, and then it’s left to be argued case by case.

Excellent responses and some rather deep analysis on the issue of “willful ignorance”. Personally however I’m not sure if anthropologists are best equipped to tackle this issue as it really heavily goes into areas of sociology and human psychology if you REALLY want to get clinical about it. There are some rather excellent psychological/sociological studies on in group/out group experimentation on how easily negative attributes towards “the other” can be created. I personally attribute this to a basic part of human instinct for tribalistic behavior. We simply tend to bond with like individuals and tend to compete with those we are not like. This is I think a very difficult challenge for a truly multi-cultural/pluralistic society that is only held in check through well… the threat of violence by an authoritarian government. As Americans we almost forget that our society is held together by ideology backed by the threat of incarceration and violence by our law enforcement agencies both local, state, and federal.

To be quite frank, I have yet to enter any society that did not observe racist tendencies. It always amazes me, for example, how some of my extremely liberal European friends will champion the Palestinian cause, wear their kuffiyah’s in street protests, and yet will rant against the gypsies in their countries and how they would very much like to see them all rounded up and shot. The shear paradox of such behavior blows my mind as I see on one hand romanticization of the other, while on the other hand, pure hatred for “the other” closer to home that they perceive as a direct threat.

The political behavior, as I see it, has many different levels of psychological/sociological foundations. However, without actually knowing on a very personal level, the particular political actor/actress in question, it all is nothing more then guessing. As any psychologist would say, you MUST know their case history before issuing any prognosis.

On the other hand, the effect of Islamophobia on society is most definitely something that can be measured and that can be tracked down. It is also something that I have much experience with dealing with interfaith dialog and speaking with some of the most die-hard Islamophobes you can imagine.

When it comes down to it, Islamophobia, like most social issues, is a very complex phenomena with dozens of factors influencing individuals who experience Islamophobia. The tendencies of the media (that the public see as “authorities on Islam” often grant an air of legitimacy to Islamophobia by featuring prominently stories about horrifically violet acts committed by radical Muslims in the name of Islam. They will very rarely show stories on moderate Muslims doing great things in the world and speaking out against extremism. It is not unlike how white Americans often have a fear of black people because of the overwhelming depiction of blacks as violent actors on such wildly popular reality crime shows as “COPS”. This show, under pressure, was forced to carefully manage its previously skewed depiction of crime and rightfully so as it had a definite negative effect on the perception of non-black Americans towards black Americans. (Watch early COPS episodes vs. later episodes and see the dramatic differences of crime depictions). It’s a very subtle issue that we are often not even aware of how powerfully it influences or belief systems and actions.

Another primary factor is I believe the political factor. This is primarily the conservative Christian right wing element in the United States that tends to have a heavily pro-Zionist agenda and who back up such conservative authors/analysts as Robert Spencer, Daniel Pipes, Bernard Lewis, and Serge Trifkovic. While all of these individuals (who heavily influence foreign policy) tend to differ in their opinions, they all tend to fan the flames of Islamophobia by ironically depicting the radical Salafi/Wahhabi interpretation of Islam as “THE TRUE” Islam. Even my friend Rick (who I’m surprised isn’t posting yet on this topic) heavily buys into this belief hook, line, and sinker as it neatly falls into line with his military mind-set, life experiences, and belief systems. All of this is much like what the deeply hated film-maker Michael Moore illustrated in “Bowling for Colombine”: America is a incredibly FEAR based society that has historically translated fear into violence. This has been true since the foundation of our nation. “Fear of the Other” I believe very easily translates into “hatred of the other.” Barring any conspiracy theories, 9/11 provided more then ample foundation for the fear part. We expressed this fear in the expression of overwhelming violence against not only Iraq and Afghanistan, but also in covert operations in Yemen, the Republic of Georgia, the Philippines, the Sudan, Somalia, Djibouti, and who knows how many other countries.

Since 9/11 the fear has very predictably translated into hatred as Muslims reacted in a predictable manner following our violent military actions and the deaths of hundreds of thousands of Muslims (many of whom were non-combatants). It was entirely predictable given the clear instructions to Muslims in their religion regarding how to respond to such violence from a non-Muslim state. From anyone who understand the powerful concepts of “honor” and “shame” within Middle Eastern cultures, it is also perfectly understandable given the constant humiliation of their societies at the hands of colonial/imperialist Western powers over the past 100 years.

In such a manner a similar process of “fear/hatred of the other” has been brewing in a parallel fashion in the Islamic world.

Quite honestly, it’s not that complicated other then all of the smaller factors that also come into play. The complicated part is the question of “how do you stop it?”

Such fear and hatred has a momentum of its own. Once ingrained into a society it’s difficult to remove unless a feared enemy has been vanquished in one form or another (as we did to the Nazis and Imperial Japanese). A from of “resolution” is seriously lacking.

Fighting members of an entire religion however (where most fellow followers of their religion tend to sympathize with their radicals that many in our society fears/hates) is an entirely different ballgame with the globalized nature of major religions today.

This brings me to my point of disagreement with what has been stated. The one issue that I object to that all of you seem to subscribe to is the assumption that Islamophobia is baseless. I think all of you have made an assumption erring on the side of multi-culturalism that all hatred of the other has no basis in fact.

It actually does. They may be exaggerated facts, but you can not ignore very real Islamic radicalism. If you do, then, my friends, you are guilty of the very willful ignorance that all of you claim to be knowledgeable about.

As the old saying goes, “it takes two to tango” and this is basic fact in peace and conflict studies.

Start analyzing that area and I think then that anthropology will be listened to more closely if it’s well balanced. But I doubt it will happen as anthropology tends to have a post-colonialist hang-over where “the West” is always the problem and the primary culprit in every such problem rather then situating Western political and sociological behaviors within a global multi-cultural context. In some cases, yes, Western foreign policies indeed are the primary culprit. However they create reactions that often fuel the conflict and hatred that must be acknowledged and dealt with if anyone is to be serious about solving such issues. If they are not…well then they should not comment on such issues if they ever wish even the slightest bit of respect from those actively engaged in solving such issues that are at the core of human conflict.

One in moderation. And a typo : “1976” should be 1967.

“They may be exaggerated facts, but you can not ignore very real Islamic radicalism.”

We’ve had lots of comments of this kind, and I’ve deleted most of them. But since Chris G.’s comment is not overtly hateful like the others, I’ll take this opportunity to reply.

Nobody is ignoring it. The post is about the inability or unwillingness to understand complexity. Perhaps you missed the line about “a dangerously inadequate understanding of the many divisions, complexities and nuances within the Islamic world”? The existence of radical groups does not, in any way, justify ignoring these complexities. That is like saying that you are justified in your misogyny because your ex-girlfriend was genuinely evil, as if every woman who ever lived must bear the guilt of what she did to you. It might psychologically explain the feelings which underly your misogyny, but it doesn’t explain why you continue to ignore the evidence all around you in the form of other women besides your ex who are not evil. That requires another explanation, one not reducible to psychological factors. (And if you are the kind of person who becomes misogynist because of one bad relationship, I’m going to go out on a limb and suggest that maybe your ex-girlfriend was right to leave you in the first place.)

[And yes, Rick, I’m deleting your posts. If you continue to try to write posts you know will be deleted you run the serious risk of being banned from this site for knowing violation of our comments policy.]

[And s.e. This is not a place to rehash Middle East policy. Please stay on topic.]

I don’t have time to constantly monitor the hateful posts in this comment thread, so I’m afraid I have to close it down. Sorry.