A striking development that has come out of the last decade’s concern with indigenous IPR and, more broadly, with the world’s mad scramble for rules of cultural ownership is the rise of global initiatives to identify and protect anything defined as “heritage.” UNESCO is the single biggest player here, but UNESCO discussions have spawned new bureaucracies in many parts of the world.

Some experts close to the process see this as a good thing. Their argument is largely a pragmatic one: at least the world is talking about this stuff and finally taking measures to protect heritage from IP piracy. If you want to get the general flavor of this, click here to read about South Korea’s current efforts to define and preserve whatever it defines as its cultural heritage.

Although I’ve met many people involved with heritage protection and generally find them smart and motivated by the best of intentions, I’m a heritage protection skeptic, which puts me in good company. For a bracing critique full of tart humor, check out David Lowenthal’s article “Heritage Wars,” published in a UK online magazine last year. Other recent contributions to the skeptic’s position include Rob Albro’s 2005 essay “Making Cultural Policy and Confounding Cultural Diversity,” as well as a recent essay by Dorothy Noyes called “The Judgment of Solomon: Global Protections for Tradition and the Problem of Community Ownership,” accessible here.

Among the points made by these critics: (1) the current passion for heritage protection gives the state increased formal control over heritage and the definition of heritage; (2) the inevitable bureaucratization of heritage tends to provide employment to elites rather than the grassroots communities ostensibly being helped; (3) state control is likely to encourage less heritage diversity rather than more; and (4) by ossifying heritage and treating it as if it were a national resource subject to rational management, heritage legislation may kill, or at least significantly distort, the very thing it attempts to protect.

As a topic for anthropological research, this is obviously the mother lode, at least for fieldworkers who can manage to stay awake during endless, highly legalistic conversations about how best to manage culture and heritage. (Oh, and they’d better have big expense accounts,too, since so much of the policy debate takes place in New York, Paris, and Geneva.) It is clearly only one expression of a larger social process of rationalization to which I’ll turn my attention in my last comments as a carpetbagger at SM.

But one has to ask: In an era when anthropology has dedicated itself to ceaseless moralizing, where should we stand on the issue? It would be hypocritical to reinvent it as just another “social problem” for dispassionate research, since anthropologists themselves were instrumental, first, in defining culture, and second, in raising a hue and cry about the commodification and theft of cultural elements via the global IP system. It’s an interesting dilemma.

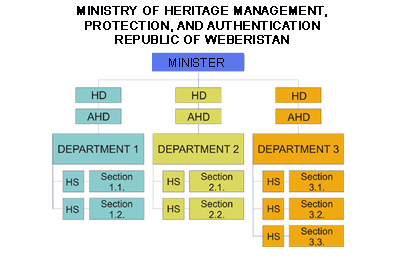

(BTW, the organigram above is an edited version of a real organizational chart from a Ministry of Culture (or was it Tourism? I can’t recall) cribbed from the website of an eastern European republic that will remain anonymous. Truth really is stranger than parody.)

Great points and issues raised. For those of us who study culture (I am actually a sociologist, so don’t really know enough about the disciplinary arguments within anthro), I think people’s values (usually well-meaning) are often in conflict with our empirical findings.

We all know that cultures are all, always-already hybrid. We all know that people have always and continue to borrow cultural forms (ideas, practices, objects) from each other. We all know that cultures continually change and are impossible to nail down in any way that is meaningful over time.

So why do we insist on talking about culture as something that might be owned or controled? My students often talk about “my culture” and/or “their culture.” (I teach at an immensely diverse university, with less than 1/2 of the students of European descent.) Yet empirically, if I stand back and look at the actual way they live their lives — their values, the objects they consume, their tastes — they also share as much as not.

I am personally fascinated by and aesthetically drawn to “different” cultures, and I value their existence. But often the urge to preserve “foreign” cultures is a middle class fantasy and an objectification of the other for the middle class’s consumption. My students object when native americans, for example, listen to rock music and are christian; that doesn’t follow their expectations of “difference,” and denies them the pleasure of consuming a “foreign” culture that they want to “preserve.”

Obviously and at the same time, we also all know that cultural change often occurs under unequal and even violent circumstances. That is, sometimes hybridization or blending (as I prefer to call it) occurs under duress instead of by choice or preference.

So I try to do three things:

1) Be intensely aware of my own love of “diversity” and to, as best as possible, not allow that value/aesthetic preference interfere in my research.

2) Focus on the dynamics underwhich cultures change, and especially (here’s my sociologist) the social psychology of culture: that is, how and why human beings create the meanings they do.

3) Reserve my value judgements for the conditions under which the culture changes, rather than of the change itself. In other words, human cultures change and adopt things they like and reject things that no longer work. Full stop. But the circumstances under which that change occurs may not.

And so I think that governmental (including UN) policies should be aimed at ensuring equality rather than at preserving a particular “tradition” or “culture” for murky (if well meaning) reasons.

In this useful installment in Michael’s series, I am so glad that he has advocated for my friend Dorothy Noyes’ fine essay in Cultural Analysis (“The Judgment of Solomon”). This (open access!) essay, which extends the arguments (and the case study) presented in her book on Catalonia (Fire in the Placa, U Penn Press, 2003), is a key, and well received, text in my graduate course on intellectual property and heritage policy issues (Contesting Culture as Property). After publishing WONC?, Michael had every right to stop keeping up with this stuff. It is great for us that he remains engaged with the ongoing discussion and that he keeps finding new ways to contribute to it, as with his posts here.

Jason, I can’t recall how I chanced upon the article by Dorothy Noyes, but I thought it was terrific; the online piece by Rob Albro, also worth sustained consideration, is a shorter version of one that he published in the _Journal of Arts Management, Law, and Society_ in 2005.

To Todd, I’d say you have no need to apologize for being a sociologist! I’ve shared a department with sociologists for more than 25 years, and I’ve learned an immense amount from them. Not that sociology doesn’t have its own problems . . . But when sociologists study institutions and institutional logics, they usually leave anthros in the dust (except perhaps in Science & Techology Studies). And since our world is increasingly ruled by institutions, anthros have a lot to learn from sociology if we can only get past our hangups about disciplinary boundaries (impassioned claims of interdisciplinarity notwithstanding).

So who out there–in any field–is doing the most provocative work on the global “management” of cultural heritage? I’d like to hear about it.

I admire your call for anthropogists actually to take a stand in relation to issues of heritage and cultural property, and I note the relative absence of response! There could be any number of reasons (as for example, my own hard drive crashing and me being without my trusty laptop for two weeks!). To my mind, your writing on this topic inflames an insufferable aporia at the heart of anthropological enterprise: the tension between our faith in anthropological knowledge and our epistemological and ethical quasi-relativism vis-a-vis other systems of knowledge or other cosmoi. For example, the adjudication of the sacred has the effect of reducing its ‘official’ significance to a question of ‘cultural identity,’ instead of, say, the fatness of pig herds or the presence of rainfall. As you have pointed out elsewhere, demands for tolerance framed through the rhetoric of liberal multiculturalism mask a kind of hegemonic condescension. In the act of ‘recognizing’ cultural difference and ostensibly ‘protecting’ it, IPR as applied to certain cultural creations may in fact encompass such creations, in effect decomposing their putative efficacy. The sacred gets re-routed through the obligatory passage point of ‘law,’ is encompassed by the interests of bureaucracy, and becomes another artifact or ‘actor’ that may be manipulated by those with vested interests (whether ‘native’ or not).

I allude to Latour — attempting to link up Kelty’s enthusiasms with your own. The problem of scientific authorship has of course been at the forefront of IPR questions. Does a Latourian perspective give us reasonable purchase on mechanisms through which IPR has managed the colonize the terrain of the cultural legitimacy of indigenous folks? One thing is clear: Latour rejects the epistemological imperialism underlying certain forms of cultural relativism. I have been puzzling the last few days, and haven’t managed to figure it out, how an actor-network analysis of IPR law applied to cultural property might help us out in conceptualizing a way ‘forward.’

I appreciated Kimberly’s response to your earlier post that not all heritage efforts necessarily keep the law or government recognition in view as a salient context or concern. I suspect that Kimberly’s take is not dissimilar from your own: to remember that there are enormous possiblities for dealing with these issues beyond the relatively narrow confines of litigation.

I guess for myself, I would endorse a similar approach: one that does not cede the field of possible positions to only those defined in law. I am pretty sure that this is the whole point of the PTC critique from Strathern, et al. What ‘cultural resources’ are available for recognizing the obligations inherent in the exploitation of cultural resources? The relatively impoverished relational vocabulary of Euro-American ‘property’ constructs would seem limiting. But then, practically, what alternatives are there?

I personally think that ‘ethical realism’ is a good stance to take with regard to questions of fiduciary arrangements and compensation. I do not, however, see how it can address the ‘larger’ problem of the relative authenticity of irreconcilable cosmoi (as in, say, ‘Enlightenment rationalism’ and Daribi myth). And it is that problem, I suspect, that makes it difficult for anthropologists simply to take a stand.

i’m fond of saying that there have been no proper actor-network analyses of networks. which is to say, no ANT approach to understanding what difference the Internet, in particular, makes to the production and circulation of knowledge (cue music for introducing my book, Duke University Press, 200whenever). And the network that makes a difference in the case of modern IPR protection is the Internet–not just because it facilitates or enables something (piracy), but because it threatens certain forms of sanctity that, previously, it was not impossible to imagine protecting without any reference at all to law, national or otherwise (i.e. security by obscurity worked before the Internet).

A Latourian analysis would probably return to the question of cosmopolitics. Commons-loving technophiles (my people!) are fond of insisting that we live in a common world and so our knowledge should be free. But a latourian approach would insist that we do not share a common world–but that the alternative is not to be content with a bunch of non-common, relativized, autonomous little domains. Because even if we do not share a common world, we do share the same planet–i.e. all kinds of consequences of our actions are visited equally on everyone, and this is as much an ecological problem of climate as it is a techno-ecological problem of information and technology. So I guess I’m with Michael here–up to a point: I’m not one of the anthropologists interested in ceaseless moralizing–but I understand the dilemma exquisitely. I think my concern would be that the people from UNESCO and the well-meaning lawyers (national and international) who are “protecting” TX be stopped before they put the finishing touches on the next crime– I want (in all my naivete) the people for whom TK is an issue to find ways to protect it, make it public, make it secret, destroy it, whatever, on their own terms and not on the terms erstwhile enlightened souls from Geneva, New York etc. insist are necessary according to international law. In this, I think there is a remarkable affinity between an emerging political consciousness around file-sharing (see especially, the film Steal This Film), and that around TK. Maybe its time for the Pirate Bay to make common cause with some of the earth’s more interesting inhabitants…

ckelty argues (rightly I think) that: “there is a remarkable affinity between an emerging political consciousness around file-sharing (see especially, the film Steal This Film), and that around TK.”

The problem is there is also a remarkable affinity between the interests of major recording companies, some software companies, pharmaceutical companies, etc. and those of some representatives of indigenous IPR/TK. That is to say, both want to enlarge the scope of IPR and control the parameters for access (including DRM). I agree that allowing UNESCO and the RIAA, Sony, Microsoft, etc., dictate the contours of the debate and the subsequent legislation limits the scope of possibilities that Kelty points to (sharing, not sharing, making secret, making semi-secret, what have you…). But, IPR talk, and the legislation that has accompanied it, is often seen as the most powerful tool in a field of narrowing choices. That is, although I am wholeheartedly in support of finding ways to *not* make/pass more restrictive legislation, I also understand where the impulse comes from in terms of positioning indigenous claims within international debates and on the front pages and in circulating debates about sovereignty. However, as much as IPR/TK talk moves into legal realms, it also, and at the same time, enlivens the networks Kelty mentions (the internets and all). The possibilities for the uncommon ground that a different commons *may* hold would certainly, I agree, benefit from crossover in these debates.

One thing I notice about this debate is that we have all, so far, tacitly assumed current notions of intellectual property, which accord to ideas or the forms in which ideas are expressed, the status of things: where, as Harlan Cleveland puts in in The Knowledge Executive things have the property that if one party has them, the other party doesn’t. The difficulty here is that ideas are not things. Party A can have an idea and give it to Party B, the result being that both Party A and Party B have the idea. So thoroughly embedded have we become in regimes that assume the application of the law of things to ideas, that we forget other possibilities.

For example, I will never forget taking a course in 18th century French literature in which the Professor pointed out that the philosophes assumed that that knowledge is a commons, properly shared by all. Thus, they frequently quoted long sections of each other’s work without citation, a practice that we would now call plagiarism.

This memory in turn evokes another. A philosophy professor casually offered one day the observation that Hegel was the first major philosopher who was also (1) married and (2) a university professor. Western thought had, he said, been going down hill ever since. Ideas, whose ultimate value had once depended on universality, had become, instead, tokens in academic status games, to which Gresham’s law applies in full; the bad drive out the good.

This view is, of course (one hopes), an excessively cynical one. Still, both these memories remind me that treating knowledge as property is not the only choice we have.

john– the distinction you mention is actually at the heart of most teaching in IPR, especially in connection with technology. the economic terms of art are “non/rivalrous” and “non/excludable”–and are frequently used to develop sophisticated analyses of the economic impact of treating knowledge as a form of property. IP isn’t the only “thing” of this kind… think financial capitalism from the 1500s forward and the transfer of ownership in terms of letters of credit, or the wealth of literature in anthropology, especially melanesia. in any case, the knowledge commons problem is still with us… read jonathon lethem’s recent article for a simultaneously enlightening an pathological expression of the problem.

One of the things that has long fascinated me about IPR debates is that where indigenous peoples are concerned, the distinction between rivalrous and non-rivalrous, mentioned by Chris, often breaks down. In *theory* it may not matter if I have access to certain secret indigenous knowledge because I’m not positioned to use it or even misuse it with any expertise. But the existence of such knowledge in “alien” hands (in an obscure BAE report in a library, for instance) may be perceived as dangerous by the source community. There may be conscious explanations for this perceived danger–the possibility, say, that uninstructed people will mess with secret ritual knowledge in ways that could threaten them or the world as a whole–but I would argue that it also unconsciously threatens cultural boundaries that are ever more ambiguous but, for all that, no less deeply felt.

There is also the scale problem touched upon in a different thread: when mass cultures, along with their media machinery, get hold of indigenous knowledge, the representation of it may vastly overwhelm indigenous self-representations.

As any number of indigenous activists say, they use IP legislation for legal and moral leverage because at present it’s the most effective tool they’ve got. Few are happy with this situation.

Kelty’s comment on cosmopolitics reminded me of a piece by Kwame Anthony Appiah who raised this topic alongside the question of property rights in Whose Culture Is It?” (The New York Review, February 9, 2006). So I am throwing on the table as it may be a good addition to the list of articles Michael provided: (For those who want a copy it is available here at least for the moment).

He basically offers a slew of fascinating cautionary tales about what happens if we cling too closely to the idea of cultural patrimony; launches a pretty strong criticism of the idea that you can really locate a body of artistic/religious/cultural works within a “nation” (being nations as we know them are a recent invention and all), and instead encourages an ethic of cosmopolitanism (not a surprise given his new book where I think he raises the topic of cultural property anew), in which he argues that “Much of the greatest art is flamboyantly international” and that people should be able to enjoy and partake in cultural and artistic work of the world.

It is a good (general) read that I found compelling and repelling; I was compelled because I agree that there is worth in “spreading the wealth” (back and forth, and all around as he suggests and gives some insightful reasons as to why we should do so—(and it helps that he is a good writer too) but, among other glaring problems, find he sets up a false binary between nationalism/nation and internationalism/cosmopolitanism, when there are a lot of situations that don’t fall easily into either category (as we are familiar with here).

So perhaps a good counterweight to Appiah, which struck as classically liberal, would be “Culture”

and Culture: Traditional Knowledge and Intellectual Rights by Manuela Carneiro da Cunha. I have yet to read but will do so once I can get my hand on a copy. And I am very excited to read it because, well I rarely dislike on the PPP publications and I find that the looser style of the Prickly Paradigm Press allows authors the freedom to more boldy explore a topic than is otherwise allowed in journals or books. Has anyone given it a read?