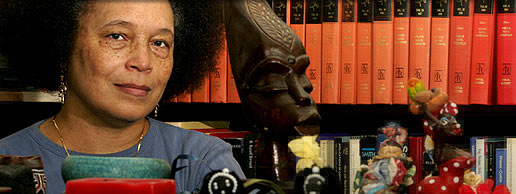

On March 3, 2016, three anthropologists at the University of Colorado–Carole McGranahan, Kaifa Roland, and Bianca C. Williams–sat down with Faye V. Harrison, distinguished professor of African-American Studies and Anthropology at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, to talk about decolonizing anthropology then and now. We share now a lightly edited transcript of our videotaped conversation: this is Part I of the conversation; Part II is here.

KAIFA ROLAND. Thank you all for coming. I’m Kaifa Roland here with Carole McGranahan and Bianca Williams. We’re all anthropologists at the University of Colorado, and we are thrilled to welcome our distinguished cultural anthropologist for 2015-16, Dr. Faye Harrison, from the University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign. We’re going to have a conversation on looking back at Decolonizing Anthropology and then moving toward the future, but who knows where things will take this. I will let Carole start us off.

CAROLE MCGRANAHAN. Faye, thank you so much for being here. In the discipline of anthropology, you can’t utter the words “decolonizing anthropology” without immediately thinking of your book Decolonizing Anthropology which came out in 1991, and was so ahead of its time. However, right now the idea to decolonize anthropology, or even decolonize the academy in some ways feels really of the current moment, that this is something new. And yet 25 years ago, you and a group of colleagues put this volume together. For anyone who actually reads the fine print, you can see that the book came out of the first invited session for the Association of Black Anthropologists in 1987. So I think where we wanted to start was with that moment, both with the volume, but also the session, and to ask, how did the idea and the impetus for this come about and even the term to “decolonize” in that moment, which just hadn’t really been used in that way, so could you can share with us a little more back from the day?

FAYE HARRISON. Well, in the late 80s the Association of Black Anthropologists (ABA) was a site where I think some very exciting things were happening. At that time the ABA had gone through many crises, it didn’t have the membership, it didn’t have the visibility that it has now with an established journal: Transforming Anthropology, with a lot of things going for it, a track record. So in the late 80s, Angela Gilliam and I, we were having conversations, we were organizing sessions. I was in a network of people who made sure that the ABA had a presence at the AAA, and on its conference program. We had just officially joined as a section, a recognized section, in the AAA, and that gave us at that time I think one invited session. And so Angela and I—I can’t remember if I came up with the idea, or if she did, but it was definitely, you know, at that moment, a dialogue, a collaboration—so we decided that we would organize a session on decolonizing anthropology.

This was around the time that intellectuals and activists around the world were using the language of decolonization in the political context, but also I think in terms of knowledge. The year before Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o had published a book called Decolonising the Mind. From an African writer’s and theorist’s perspective he wrote this book which made a major impact. He focused, of course, on African languages and the politics of using colonial languages, but the book was amenable for a wider set of conversations and interpretations about knowledge itself. And so I think the inspiration came certainly from our playing with that title.

We were also playing with the notion of decolonization given that there was a lot of conversation in the 70s and the 80s about the colonial baggage of anthropology. We were reading Talal Asad, Diane Lewis, Bernard Magubane. These are all people who situated anthropology in a broader colonial context. And they were people who realized even with the fact that history has moved forward, and that we are supposedly at a post-colonial moment, neo-colonialism is still a reality. We were grappling with what we call today the enduring coloniality of power, political economy, and knowledge. That’s what I recall. That was the moment. At the time, I was an assistant professor, had come out of graduate studies at a time when I was really studying the political economy and politics of different areas of the world, particularly Africa and Latin America. And so I was very much in tune with the language that Latin American and African intellectuals were using, and of course that American and European scholars were using when studying those areas of the world.

CAROLE MCGRANAHAN. Hearing all this makes the argument you make in the volume even clearer. In the introduction you argue that in order to decolonize anthropology we need to be reading who you called at the time third world intellectuals. We need to bring those ideas and concepts into our scholarship, and recognize this a literature that goes back far.

You wrote that the goal of the book was “to encourage more anthropologists to accept the challenge of working to free the study of human kind from the prevailing forces of global inequality, and dehumanization, and to locate it firmly in the complex struggle for genuine transformation.” I think right there is something key, the idea that anthropology can’t just be about studying people. But anthropology has to have, built in, the idea of transformation, and making life more bearable for everyone, everywhere.

FAYE HARRISON. Mmmhmm. Mmmhmm. Yes.

CAROLE MCGRANAHAN. And so, can you give, the three of us, we were still coming of age anthropologically [laughter] when this came out, can you give us, just a little bit more on the sense of the feeling at the time of what was possible?

FAYE HARRISON. Well, it was the feeling of the time. I think it was not all anthropologists at the time—

CAROLE MCGRANAHAN. And nor is it now, right?

FAYE HARRISON. Of course. I was fortunate to surround myself, I was going to say “to be surrounded,” but of course you have to seek out similar birds of the same feather, as it were. I had come out of graduate training earlier in that decade and I had benefitted from an ambiance where I had mentors who were immersed in in this type of feeling of, possibility of, necessity that anthropology transcend the limits of earlier history.

So, even before we were using the language of Sankofa, that really was a moment when my graduate education took place in the midst of those reconsiderations of the field. I was a student of Bridget O’Laughlin, who left US academe—Stanford—to be closer to the front lines of intellectual and practical struggle for African sovereignty in Mozambique. Because she felt that Stanford is a great place to work but is essentially a bourgeois institution. As a Marxist and an Africanist, would she be satisfied over the years with raising the consciousness, and making the children of the bourgeoisie and their middle class supporters more liberal? Or would she like to actually go to Africa, in southern Africa where you know there were struggles, armed struggles, for liberation, and their vision of independence was already informed by some of the failures of earlier experiences in independence?

Bridget made such a profound impact on me. The fact that she would forfeit a career path that most of us would die for, and to go to Universidade Eduardo Mondlane to work with unconventional students, whose task was really to go into the countryside to re-organize agricultural production. That is political organizing, economic development, but informed by the most progressive research, in what she did, anthropological political economy. So that made an impression on me. This is a possibility, this is a direction, that I would not follow, because I wanted an academic position in the United States, but I feel that my sense of the field, the profession, and the intellectual task was very much influenced by Bridget.

Then there was St. Clair Drake, who in a sense was a historian of non-canonical anthropology, who was of what I call the DuBoisian or the Afro-diaspora trajectory and tradition of scholar-activism. His sense of who are intellectuals, what do they do, for what reason, and for whom was very much consistent with the sort of ideas that I’ve been playing with, working with, struggling through, and which made a project like Decolonizing Anthropology, the three editions of that book, possible. I’m just heartened to know that, the fact that it is in three editions now, and an e-book as well, shows that those ideas that were crystallizing in the late 80s are still very relevant today. Although the world has changed, this is a different moment, but I think the underlying, the fundamental issues at stake remain much the same.

I still consider myself committed to the critical project of decolonizing anthropology. Sometimes I use other language: reworking anthropology, Renato Rosaldo called it re-making cultural analysis. My former student and friend Pem Buck says creating an alternative anthropology, and Arturo Escobar talks about anthropology other/wise, with both other and wise being extremely operative. So taking the subaltern, the indigenous, the indigenized and the minoritized seriously. To the extent that we truly recognize people’s full humanity, that of course means we recognize their wisdom, their intelligence, their capacity to produce forms of knowledge that include potentially powerful interpretations and explanatory accounts of the world, which give us the clues to then create strategies to change the world. I feel very fortunate to have been in an environment where these conversations were going on all the time. Very much, very often outside the formal curriculum, but they helped to constitute the intellectual milieu. And so I came of age as an anthropologist with all this in my head.

CAROLE MCGRANAHAN. In Outsider Within you tell a story of being an undergraduate and having Louise Lamphere handing you Dell Hymes’ Reinventing Anthropology. Of your realization that anthropology is something that’s not just about coming up with new theories, but something that can be reinvented as a political project.

FAYE HARRISON. That’s right. That was momentous, and it took a while before it seeped in. That was a formative, seminal moment that I would come to see my whole purpose for going into anthropology, to be part of a movement to reinvent, to remake, to decolonize it. And at least to lead a spirit of that legacy for future generations, because anthropology is not decolonized today, but I am happy to say there is a critical mass of kindred-thinking people who are doing, I think, fantastic work. With every generation maybe we can go a little bit further, more or less. There were some people in past generations who were phenomenal. We will never approximate their impact. But I’m pleased with what I see in your generation. But I’m also very cognizant that anthropology is in danger, as most of the social sciences, or disciplines of knowledge, are. Because much of our discourse, although it may sound even revolutionary, we operate at institutions that are under the assaults of the form of structural violence that is corporatization and neo-liberalization. We have to be very vigilant and careful that the progressive projects that we do are not appropriated and then refashioned in forms that really undermine the very epistemological and political agendas from which our projects have actually emerged.

BIANCA WILLIAMS. So, we have a conversation all the time about Audre Lorde’s “master’s tools, master’s house” and as I’m listening to you I’m thinking that on good days I love my discipline, and believe that it has transformative power, that’s why I am trained in it. On bad days, [laughter], that dream sometimes falls apart. And so I’m wondering, not only in decolonizing anthropology, but decolonizing the academy, decolonizing the world, what gifts do you believe that we have as anthropologists to do that work? What are the special things about our training or about our belief system that allow us to do that kind of work?

FAYE HARRISON. Well what appealed to me, and what appeals to many people I know, why we’re not sociologists, or cultural geographers, or lawyers for that matter, is the participatory ethic. Of course, it can be implemented in ways that are egregious. But when we do it right the fact that we immerse ourselves in everyday lives and demands of ordinary people all over the world. We humble ourselves to being sort of re-socialized and enculturated, which means you show your vulnerabilities, and you know you go through being a child again—

BIANCA WILLIAMS. So you have to transform.

FAYE HARRISON. –and so you have a role reversal in that process. When you do it right. And to the extent that we go beyond those models of fieldwork which are really based on what I call the mining and the extraction of data as though it’s a raw material that needs to be then refined and created into some other sort of commodity. If we can get away from that model which is consistent with basically a market, a capitalist market, commodification, competitive individualism, hierarchies and whatever, and realize that the people who make our research possible are much like us. They have knowledges, sometimes very sophisticated understandings of the world, and embedded in those understandings are what we call theory, although the way we defined it and operationalized it often created dichotomies or hierarchies of knowledge which relegate what I would call the vernacular, the every day theories, as, we treat it as just raw data, as description whereas “I’m the one who is authorized to produce data,” I mean, to produce these explanations that we call theory. That sort of model of appropriation, expropriation, very much based on hierarchies, on a division of intellectual labor that is designed to render many of the people who coproduce knowledge–and here I include formally trained scholars–to render them glorified informants.

I think there is a possibility to ground what we do, to situate the inquiry we do in the real world of people and to decenter ourselves enough so that we can absorb and speak with rather than for whomever– the people, the cultural situation, or whatever. So I think the participatory ethic is how we can find out the most socially responsible way, the most democratizing, decolonial way to enact it; it means people are more than variables on a survey. It’s based on an intensive commitment of time.

Many anthropologists return to their fieldsites or similar ones again and again over extended periods of time to get it right and to follow through in recognition that one snapshot moment when we do ethnographic work is amenable to change and becomes more complex and nuanced the more we learn about it in the nonlinear flow of time. I’m thinking of the work I’ve done in Jamaica over the years, and the times I’ve spent in Cuba and South Africa intermittedly, witnessing shifts, sometime quite stark and often subtle, in government policy, economic strategies (from both the top and the bottom), and the sociopolitical climate and its implications for how ordinary people take action. With the participatory ethic over time, we become more familiar with people as they live with and through change–as they make change happen. Some of us are inclined to establish coalitions and alliances that enable us to struggle with our research participants to help effect the direction of that change. The roles we play vary along a continuum of engagement that includes advocacy seeking to inform and change US public opinion about a place and what’s going on there. I think of the compelling academic and public writings that Christen Smith has been doing about antiblack violence in Salvador, Bahia and the React or Die movement built to combat it. I also think of Joao Costa Vargas’ role in facilitating connections, communications, and travel between grassroots activists in LA and Rio around organizing against lethal police brutality in US inner-cities and favelas. And there’s Keisha-Khan Perry’s on-the-ground participation in black women’s organizing in poor communities in Salvador. I mention these three examples, because I’ve been thinking about them in relation to Black Lives Matter here in the States and the striking parallels in Brazil and other parts of the Black World that more people need to know about. Of course, there are many other examples of anthropologists’ engagements in hopes of change.

I’m very much interested always in some ramifications or a trickle-down effect that somehow affects the very materiality of life, sociality, and national and global integration, reintegration into something other than what your work, Carole, calls “the imperial formations” that are all around us. So that’s part of it, the dialogues with people, treating them as people, being exposed to the texture the flux, the oomph of their lives. You don’t get that if you’re doing a survey, where you’re there for a minute. Methodologically, you may have something that is representative of larger populations through these rigorous samplings, but sometimes you do triangulated work where you put those quantifying sorts of research in conversation with qualitative approaches. I think for anthropologists, ethnography is more than what it is for a lot of people who do ethnography outside of our discipline. I’ve been on committees where people do dissertations; they went someplace for the summer and, you know, they were physically there, they observed, they had some interviews, and that’s their ethnography. And I think for us, ethnography is much more methodological. Even though we may sort of talk about participant observation, informal, unstructured interviews, we do lots of different things in order to do a proper, robust ethnographic study and analysis. If you’re someplace in the midst of things long enough, these things will come to you. You have the opportunity to ferret out information from lots of different locations, intersections, channels. Some of which you hadn’t even thought about when you designed your research proposal and got your funding. There’s room for improvisation, there’s room for the sort of dialogues and relationships that allow us to collaborate in a multiplicity of forms. We can speak in voices, if we wish to, that resonate with, and are more similar to, the voices of the people who answer our questions, as opposed to speaking in a voice that is so alien to that. I think all those possibilities are there in the types of ethically and socially responsible ethnographic praxis that I have observed, that people I really admire are doing over time.

It’s lived. It’s embodied.

CAROLE MCGRANAHAN. I read an essay this morning that was talking about ethnography as only observation and interpretation.

FAYE HARRISON. That’s very reductionist.

CAROLE MCGRANAHAN. Right? And I thought where’s the, never mind the ethical, but also the participatory, the immersion? A Tibetan friend of mine, Gyatso, talks about getting to what he calls the zhag tshi or grease of life, the stuff that makes things taste good. The flavor of life.

FAYE HARRISON. Or, [to Kaifa Roland], as your student said in the workshop, the silt and the mud.

CAROLE MCGRANAHAN. Right, right. And the oomph.

FAYE HARRISON. I can’t even say it! It’s so visceral, right?

[All laughing and agreeing]

KAIFA ROLAND. We’ve talked a little bit about origins of Decolonizing Anthropology. One of my very favorites of your works is Outsider Within.

FAYE HARRISON. Thank you.

KAIFA ROLAND. I always want to call it “Sister Outsider,” because—

FAYE HARRISON. Right! Yeah! [Laughs]

KAIFA ROLAND. Because for me it has a more feminist and feminine and female voice.

FAYE HARRISON. But that title had already been used.

[All laugh]

KAIFA ROLAND. But that’s kind of what I want to get to. You come to the title “Outsider Within” from Patricia Hill Collins. I wondered if you could just talk a little bit more about the origins of that. I’m fascinated by your paralleling, or her paralleling, of the work of domestic workers and social–

FAYE HARRISON. Oh yes.

KAIFA ROLAND. –Women of color social scientists I should say. Can you talk a little bit about the, the project Outsider Within, but also that origin story?

FAYE HARRISON. Of course, like many black feminists, or I think just well-read social scientists particularly interested in the black experience, and particularly black women’s experience, we read Patricia Hill Collins. Her work has had a tremendous impact. There’s a long history within sociology and the social sciences talking about a “marginal man” figure, and usually it was man. Or of ideas of marginality and the sort of betwixt and between, sort of being at the crossroads of these sort of entities and whatever. And so Collins fashioned this notion “outsider within.” Using the domestic analogy is perfect, because you have help that’s really not part of the family, but you sort of mask the relationship of exploitation by saying: she’s like part of the family, auntie Josephine. And so they’re outsiders but they are within, which means they are privy to things that happen that are usually hidden, or hidden to people who are not part of that club, that family, that discipline, or whatever. That you belong, but you really don’t belong, but historically—

KAIFA ROLAND. Yes, as we see so clearly in The Help…

FAYE HARRISON. I really liked when Renato Rosaldo, in Culture and Truth, talks about people of color in subservient roles. He was talking about Chicanos, African Americans, and how we have been inside the halls and the homes of privileged white people, and so we know a lot about them that they do not know about us. They do not go across the railroad tracks into our homes, to really know us as full-fledged, three-dimensional human beings. That really struck me. Once we rise up and get PhDs, we don’t cease belonging to those communities. Even the people who try to move on up and sever their lives from their past … something will happen at some point to put them in their place. And so, we never fully belong.

So “outsider within” as a privilege, but also as an experience where you are subject to the sort of injuries that have been documented by the reports that the AAA’s Commission on Race and Racism in Anthropology has attested still exists in the 2000s. The same discriminations they found 1973 when the first report on the status of minorities in anthropology was done based on very thin data. Today the results are pretty much the same. So have things changed? There are more of us in the academy, but the stories people tell about what they’re experiencing show that they don’t belong. They’re out of place.

To read Part II of this conversation, click here.

thanks for the much needed conversation(s)!