Call it what you will: an anecdotal and impressionist narrative, or a set of strung-together fieldnotes, collected over years of living and working with people across class lines (in my own home construction sites, in an NGO working in the space of education, in my locality with maids and workers and neighbors) suspended indefinitely in a life of participant observation. The following is a story of the ways in which the future frames us—in both senses of the word.

It is a week before the second spate of massive rains will flood Chennai city, causing the worst flooding the city has seen in 100 years. We are at Home Center on TTK Road in Alwarpet, one of the new home and lifestyle chains which feel much like a localized version of Bed, Bath, and Beyond—down to lighting and layout. We are with my parents and elderly uncle, who is fond of remarking on each instance he finds of facilities and services being “just like in a foreign country.” These days, there appear to be many such.

Back home in Pondicherry, a tiny little “modular kitchen” furnishing, appliance, and homeware showroom has recently opened up, directly across from a housing block, built thanks to the Integrated Housing and Slum Development project sanctioned under the Jawaharlal Nehru National Urban Renewal Mission (JnNURM) scheme. Neighborhoods like this one, off-center from the old heritage “white town,” are very mixed, with more expensive apartments and private homes tucked into unlikely nooks, adjoining slums, ‘low income’ government-built tenements, cow sheds, dhobi ghats (washing areas for laundry), and un-walled private plots by default used as open dumps. I’m walking past with a woman, Selvi, who works as a maid in a house nearby, and lives in the government quarters, as they’re known. We remark on the presence of the new kitchen store. “Do you think of going there to buy things?” I ask, somewhat disingenuously. She laughs. “Us? It’s only people like you who can go into shops like that.” I don’t bother to clarify that it’s not the kind of shop I would really think of visiting.

It’s an insignificant little exchange which pinpoints something more than just class difference, something the marketers have always known: differentiated levels of access to consumer goods also create scales of aspiration and desire. Even the poor are rhetorically always future consumers. The little kitchenware shop situated across from a low income housing block is in its way a “narrative machine” (I borrow the term from Charles Piot); whether the fantastic possibilities it holds out are ever realizable or not, they are there, they frame us both, and we both know it. I can no more tell Selvi where to shop or what to buy than the developed world can insist that countries like India should control greenhouse gas emissions. In the overarching narratives of our combined futures, whether we are hypersubjects or hyposubjects or unwittingly stranded in between is entirely unclear.

In Selvi’s own home is a modest-sized recently purchased flatscreen TV and a brand new top-loading washing machine, which she needs my help to understand how to use. We meet here as equals: host, guest, and fellow washing machine users. The salesman has told her the machine dries clothes out. I need to clarify that they always mean “90% drying,” so clothes come out wrung but not dry. Her friend Sudha lives next door, in a single room apartment that was once part of an old government office block. So long had it been unused and locked up, local residents stormed and claimed it for their own, even though they now communally must share common toilets—it was their only means to secure housing. Sudha tells me of wanting to live someday in a big house with a room for each family member, and cutlery “of the sort that only foreigners have.”

For these women, the future is in some sense all around, in its uneven distribution, in the lives other people are already leading, in the shops that are already there selling sheet sets and drawer-organizers, in the promises of a not-quite-accessible lifestyle based in consumption. Their husbands are carpenters, painters, plumbers, electricians, masons; they are by no means the “destitute” of the National Council of Applied Economic Research’s profiling of consumer households, nor certainly the “very rich,” but the actual builders of the new economy, poised somewhere in between just-sufficient and not-quite-enough. In this world, political arrangements—of the sort one makes when the Congress election worker comes with a new pressure cooker two months before impending elections—are vital, for these carry other promises, moral obligations, and the possibilities of leveraging forms of agency, identity, and difference that are typical of patron-client relationships in ultimately securing rights. If the capacity to aspire defined as the capacity to consume cancels out social differences—it is “impossible to tell a person’s caste from a person’s brand buying behaviour or his or her home,” as market research consultant Rama Bijapurkar asserts—the pragmatic political arrangements of daily life and work strongly re-assert social differences. Like it or no, the two democratic registers co-exist.

So it is that the future can only be a near-term prospect. Everything else is an abstraction in the same way that navigating roads by names was an abstraction that Google maps India had to rectify via the use of landmarks: concrete, identifiable, recognizable, and above all stable positions. I want to talk about toxicity and post-carbon futures. The women I meet tell me instead about the efficiency of garbage workers, and how all anyone needs to do is petition the municipal office (“you know the one office that at the next cross-roads?”) to have them come clear the piles of plastic accumulated in a nearby plot, torn to shreds by roaming livestock. I want to talk about risk and speculation. The woman who runs a chit-fund scheme assures me there is none, because she deals only with people she knows—and asks me then to play broker at the local NGO at which I have a role: she needs help with her son’s higher education. I want to talk about preparedness for impending instabilities, about the Chennai floods and the cyclone that devastated Pondicherry in late 2011. Sudha is unmoved. “Our parents faced much more of all that. Our lives are better now. Our children’s lives will get better still. Floods and cyclones like that are rare—what did they say? Once in a hundred years, once in 30.” I don’t dare ask about the futures cancelled by rapidly wasting planetary support for all our many commodity forms. I listen quietly instead to affirmations of faith in conventional narratives about education and its promise of finding work. Or about how people watch the price of gold, not because they are speculators but because they are buying some certainties for their daughters’ futures.

But I’m also struck by the denial of the gamble—not because my horizons are set farther on, but because for every story that tells of kinship and marriage as economic futures, of how a mother’s brother should present his niece with gold at certain key moments in a girl’s life, there are ten which recount how the uncle is a drunk, and has no means. There is an undeniable fragility to all these narratives of the future, best not acknowledged.

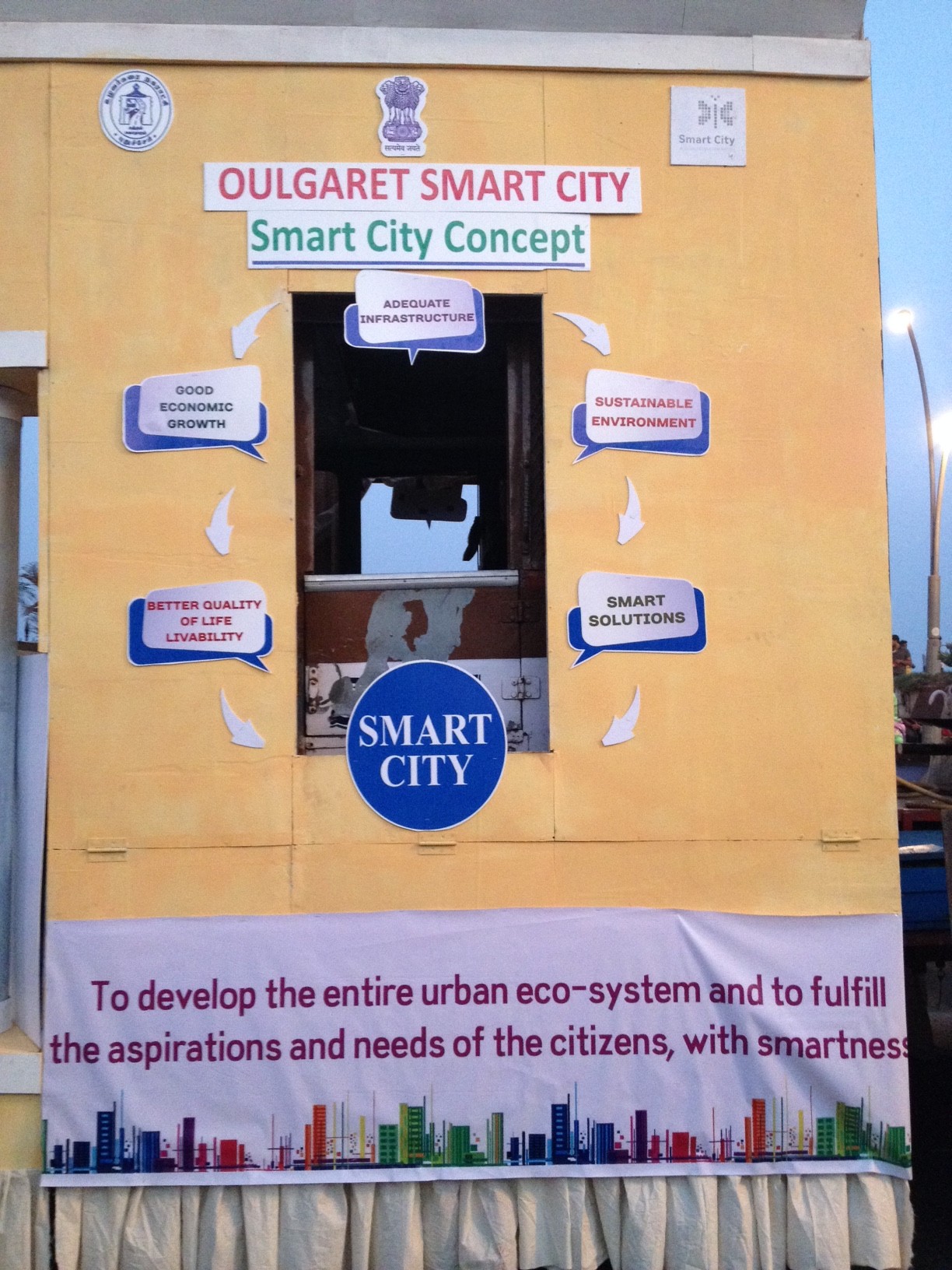

I started out wondering both what to do with future scenarios that seemed so alien in this part of the world, and what the future might look like, imagined from here. As if in answer to both questions, a Republic Day float appears on the beachfront promenade, announcing the SMART city designation conferred on Oulgaret Municipality (Oulgaret adjoins Pondicherry, and just happens to be the present Chief Minister’s constituency). The “Smart city concept,” it announces, converting the SMART acronym into a word, is “To develop the entire urban eco-system and to fulfil the aspirations and needs of the citizens with smartness…” The float offers a concretization of this idea, complete with recognizable and stable landmarks: wide roads, green spaces, and tall glass buildings with helipads atop, some apparent solar powering. These are clichés to me, perhaps, and the promise of smartness uselessly indefinite, but they confer the same pride of ownership and prestige that the chit fund lady finds in her new Panasonic smartphone: “That, I had to have,” she says, clutching the device to her chest and tucking it safely into a purse though she claims she barely knows to use it, “I just had to have it.”

When we conducted “playshops” with children from local schools a few years ago in a project that wanted to capture how school-going kids visualized the future, it was striking how the daughters and sons of masons and carpenters found it hard to think beyond homes made of concrete and wood, no matter the fantastic prompts given to them. We think with what we have, and with the futures already there. And what we have is the hope of consumption, SMART tech being only the latest manifestation of material progress and empowerment so-defined—powerful, driving vectors which cannot be simply dismissed as unsustainable just because our horizons are different or our critiques have gone farther.

As John Rundell puts it, “We all wait for futures—yet not for the same ones, nor in the same way, nor at the same tempo. Modernity, because of its multiple worlds and their temporal horizons, entails that waiting for the future has multiple, clashing and even overlapping effects, affects and modalities…” To some extent, it’s the contrast between the democracy of the queue in the bank or the public hospital waiting room, and waiting in the thick of social relationships and political arrangements that order values and lives in separate queues. Rundell continues: “We can wait anxiously, impatiently, resentfully, with frustration, or perhaps with patience. This indeterminacy, finitude and uneasiness is what both increases and decreases the suffering and torment, the horizons and possibilities of those who wait.”

Deepa,

Just a bit of comparative data. Japanese marketers use the expression “antenna shops” for what you, following Piot, call a “narrative machine.” I sense an interesting difference between these two expressions. “Antenna shops” suggests an attempt to understand what it is to which consumers do or do not respond favorably. The antenna shop detects potential demand. In contrast “narrative machine” suggests an imposition, an implicitly illegitimate forcing of a certain future into consumer consciousness. My Japanese colleagues who want to be “half a step ahead” are wary of the not-for-me response that Sevi’s comment illustrates.

Thanks for that, John, really interesting! I’ll have to file the expression “antenna shops” away for later use, so thanks much for that. Out of curiosity, what sorts of shops are we talking about? I mean, what are they selling, if the point is to keep fingers on pulses–what objects allow the measure of such trends? I don’t see narrative machines, however, as only impositional. Clearly, they wouldn’t work if they, too, didn’t have a sense of consumer responses and needs, and if they didn’t try to gel with those–though I’ll agree that their work is less about diagnosis than delivery. And spin! I suspect they’d read Selvi’s not-for-me comment as more like not-yet-for-me. Which is of course the logic at the core of consumer citizenship.

Deepa,

I just did a Google search for “antenna shops” and the first thing that popped up was an article about shops operated by thirty of Japan’s prefectures, aiming to stimulate interest in tourism and local products. Here is the URL: http://www.getaroundjapan.jp/node/172

Lots more where that came from.

P.S. That “Not-yet-for me” is a very important insight, especially in developing markets.