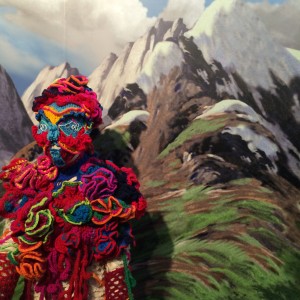

More drinks. This time in the midst of a madding crowd, soon after returning from Krakatau, with an Icelandic artist known as Shopflifter. She was wearing a remarkable head piece she humorously called a ‘brain catcher’. We were at the opening of the Björk show at the Museum of Modern Art and it was too crowded to see anything so I just drank and admired the brain catcher. I went back later to see the show. I went in the quiet before the crush of tourists to put on headphones and hear the biographical poetry that accompanied the material objects. I think the critics, universal in their evisceration of the show, may be a bit like archaeologists unable to see the important data in their spoil heap. The show wasn’t about the questionable directions of MoMA, its director, or contemporary art overall. The work itself, Björk’s work, was about the intimate and sometimes painful entanglement of human biographies and the physical planet. This seems outside of what critics can soundbite or archaeologists and geoscientists can quantify and yet it matters.

I’m wondering how it is possible to listen to data a bit more. I’ve never been entirely opposed to listening to the violence and change possible on our planet in that I’ve long been a fan of the concept of what is ‘probably the loudest piece of music ever written’, Jón Leif’s Hekla. It was a musical volcano, meant to approximate an eruption of the Hekla volcano the composer witnessed in 1947. To convey the indescribable, unquantifiable, un-writable sense of volcanic eruption the composer wrote the score for unattainable or unplayable instruments like massive church bells and rapidly repeating shotguns. The musicians had to make do with rocks and ships’ chains and steel tubing from the Reykjavik dockyards for the 1964 premier of the piece. It was loud but I would argue that it was not noise, which in data terms is defined as meaningless. There can be music in the seismic signals and internal shifts of the planet, I know this from the seismologist I drank with in my prior post. Our environmental data are starting to get louder. It is not noise, either. Just take a look at this intriguing and somehow pleasurable (though it shouldn’t be) project out of the University of Minnesota if you haven’t seen it yet: a student put Northern Hemisphere temperatures since 1880 to music. We can, indeed, listen to our data.

Do we record and focus upon the wrong things while trying to understand the Earth in our era of environmental anxiety? I wonder about this. The sciences are vitally important, but I am thinking I might also be well served in taking physical geology lessons from Björk. She’s marvelous at explicating crystal formations, plate tectonics, or volcanic landscapes in that she clearly annunciates the way that each human life is joined to that of the Earth. Our biographies and that of the planet are tangled together. This is not insignificant and is not outside of either an art museum’s remit or scientific inquiry. Science, whether of the social or harder versions, can be ecopoetic. Our data are lyrical, given the source material.

0 thoughts on “Listening to Physical Geology. PART 2: The ecopoetics of data, a few lessons from Björk”