[Savage Minds is pleased to run this essay by guest author Donna Goldstein as part of our Writer’s Workshop Series. Donna is Associate Professor of Anthropology at the University of Colorado. She is the author of Laughter Out of Place: Race, Class, Violence, and Sexuality in a Rio Shantytown (University of California Press). She is currently writing about pharmaceutical politics, bioethics, regulation, and neoliberalism in Argentina and the United States, and is investigating the history of genetics, Cold War science, the health of populations, and the future of nuclear energy in Brazil.]

“Going through the Brazilian Portal. Hold on! We are heading into Porto Frade, a gated community of the rich and wealthy! Everything functions here!” These are the words of my Brazilian research co-pilot, Nelson Novaes Pedroso Junior, during our recent field excursion to Angra dos Reis to explore perceptions of risk and the role of the nuclear energy plants in the region. Together with doctoral candidate Meryleen Mena, our research team entered Porto Frade, a securitized community not far from the Angra I and II nuclear complex in the state of Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. It is a gated community and a world of yachts, million dollar homes, mostly empty streets (in March of 2015, at least), and security apparati just within the five-kilometer mark of the emergency evacuation plan of the nuclear plant.

This is not only a less well-known Monaco or Sausalito, but also a community of second homes that are underutilized by their wealthy Brazilian owners. The homes are perfect, the gardens well-kept, and the yachts are supersized. In Porto Frade you can find restaurants with French names and menus that would please the most discerning cosmopolitan foodie. If I had no social conscience at all, I could probably have enjoyed my late Saturday lunch that much more. But knowing a tiny bit more about the broader context made enjoyment somewhat difficult. One needs a good sense of humor and sense of the absurd to work in Brazil and to write about its contradictions.

Right next door to Porto Frade is the other side of Brazilian reality, the other side of the portal. There lies the neighborhood or village of Frade, a small tropical town with approximately twelve thousand residents according to the 2010 Census, but probably closer to twenty thousand by now. Residents in Frade have come and settled there from other distant and less privileged parts of Brazil in order to offer their labor for building Brazil’s Angra nuclear plants. After Angra I and Angra II were completed in the 1980s and 1990s, Frade’s residents remained. Now, new residents have been coming in a similar wave to an area known as Parque Mambucaba to offer their labor for the construction of Angra III. In a manner familiar to observers of large construction projects around the world, these towns are built in reverse. The laborers and then their families come, and the infrastructure—proper sewage, electricity, water, telecommunications, health care, schools—arrives later. Before long, these makeshift areas acquire the look of migrant towns, complete with the smell of raw sewage, of quickly constructed buildings, and of a certain kind of kitschy but lovable tropical decadence. One cannot blame these laborers for having migrated for employment opportunity, but the lack of foresight by the large construction project planners is stunning.

The rapid and unplanned development in Frade and Parque Mambucaba is familiar, but still a disaster in many respects. This is also true of the better-planned wealthy gated communities next door that have the feel of a Truman Show set. Yet, when Brazilian environmental activists speak of the ecological disaster of Angra, they tend to be speaking of the thousands of migrant laborers who come quickly for work on the construction of Angra III, and point to the stresses Frade and Mambucaba place on the environment. These communities are established in areas without infrastructure, and end up putting the costs back onto already underserved local communities. Environmentalists also speak about the hidden costs of building the nuclear plants in this beautiful tropical paradise and of how these costs are shifted onto already burdened and impoverished local populations. The Porto Frade community is harder for them to critique. While it is built with excess wealth that comes from elsewhere, the odd thoughtfulness and planning of the community give it the appearance of having arrived from some future universe. Porto Frade is a sort of science fiction “portal” that blasts the visitor into Brazil’s modern and wealthy future where structures are built properly, money is free-flowing, and first world amenities are plentiful. Who wouldn’t want to eat oysters and fresh fish at a place called Le Bistro Chez Dominique on the banks of the Brazilian Riviera? Barely part of the nuclear energy conversation is the fact that the side-by-side growth and expansion of Porto Frade and Frade has displaced local populations of fishermen who lived in the region for generations, and has had negative effects on indigenous and quilombo populations living nearby.

How to protest? What to protest? We could probably all agree that the era of nuclear activism appears to be over. When I asked my introductory anthropology students at the University of Colorado what they think of nuclear energy as a future energy source, they don’t really have a well-formed opinion. When I taught about Fukushima and Chernobyl (using Adriana Petryna’s Life Exposed), and students learned that elderly workers at Fukushima volunteered for the toxic clean-up work, they found that outcome to be a good solution. Fukushima, Chernobyl, and Three Mile Island have all been successfully framed as exceptional events to this new generation, and risk, according to nuclear energy proponents and modernity’s logic, is involved in all technological projects.

The lack of politicization on nuclear issues is not unique to my students’ youth or class position. One of the long-term Brazilian anti-nuclear activists we recently interviewed in Brazil mused about the current political sensibilities about nuclear energy. “Anyone not in favor is mute. . . In terms of how things are in Brazil, there isn’t the historical difference that used to characterize the left and right anymore. It’s all the same. . . It was the Worker’s Party (PT) that approved Angra III, after all.” He was referring to the sensibility that positions just about everyone with no opinion to be in support of the nuclear energy project, not just in Angra dos Reis where the two existing nuclear plants in Brazil have been functional since the 1980s and 1990s, but also for the potential nuclear energy expansion throughout Brazil. This muted support for nuclear energy exists in spite of the awareness of the infrastructural precarities that still characterize so much of daily life, particularly in Frade, Parque Mambucaba, and the city of Angra itself. But the real source of muted de-politicization on the nuclear issue exists in the major cities.

Our research with engineers within the Angra dos Reis nuclear plant who are charged with different aspects of safety and security within the nuclear complex offers an eye-opening perspective on how we have all arrived here. “You get on a plane, don’t you? All industrialization and technology involves risk,” the engineers remind us. I hear this provocation so often I start to doubt my own deep feelings that question the security and safety of Angra. I see a two-lane highway predisposed to landslides, internet access that in a very nice hotel in Angra is prone to failure, and the more obvious precarities of infrastructure visible in places like Frade. But then I realize that Porto Frade (the portal) exists in order to allay those fears.

Twenty years ago, in 1996, a group of Brazilian political theatre satirists inspired by the renowned founder of the Theatre of the Oppressed Augusto Boal planned a “simulation within a simulation” evacuation exercise in the city of Angra dos Reis. Anti-nuclear activists positioned themselves inside of the official simulation, partially, it seems, to point to the problematic aspects of the evacuation scenario. One person we spoke with who participated in this exercise enacting the role of a woman from a psychiatric facility; another participant played the part of an indigenous man not fluent in Portuguese. In this “scene within a scene” a participant actually had a heart attack and could not obtain proper treatment, thus truly disrupting both the official simulation and its counterpart. The performance of the activists within the simulation was carried out to bring awareness to the potential panic and chaos that they believed would characterize the population in the event of a real nuclear accident.

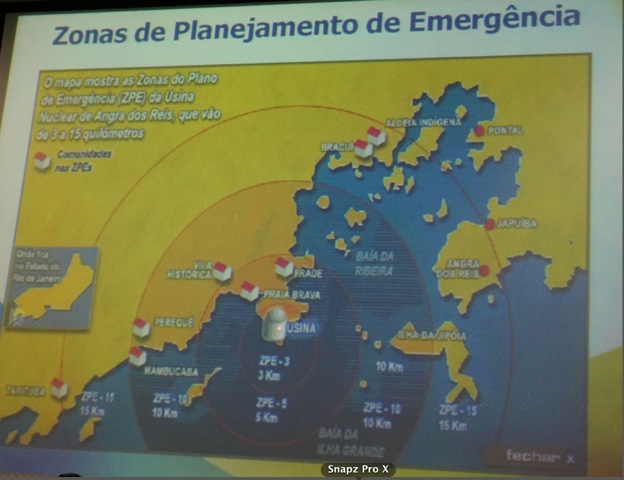

Today some of those same activists note that if the sirens suggesting evacuation blow in 2015, people would probably hardly pay attention. One activist suggested that nobody would bother to evacuate. An administrator high in the evacuation command hierarchy expressed concern that present-day youth are more interested in video games and smart phones than in the serious nature of an emergency plan. This official explained that the city of Angra dos Reis would most likely not evacuate because it falls past the ZPE-10 (Emergency Plan Zone) radius, and thus outside the boundary of the plan of evacuation in the case of a nuclear emergency.

I am not sure if the response of the 170,000 residents of Angra would be panic or malaise, but both potential responses worry me. Anthropologists who find themselves in projects critical of the prevailing drive to self-destruct must listen to distinct voices and attempt to find a grain of sanity within the contemporary logic of risk. We must have a sense of humor about what we are observing around us, or we are doomed. During our fieldwork our team survived our collective fears by highlighting some of the absurdities we witnessed. Now that I am back home in Colorado, I am still trying to find the humor in the present we currently inhabit, but it escapes me.

Whoah. Was that a Ntozake Shange reference in the title? I haven’t thought about that play in, like, 20 years.