[This invited post is submitted by Discuss White Privilege, an anthropologist who has written extensively to refocus the academy’s critique of racism on itself. We respectfully ask that you review our Comments Policy before responding below. Thank you. –DP]

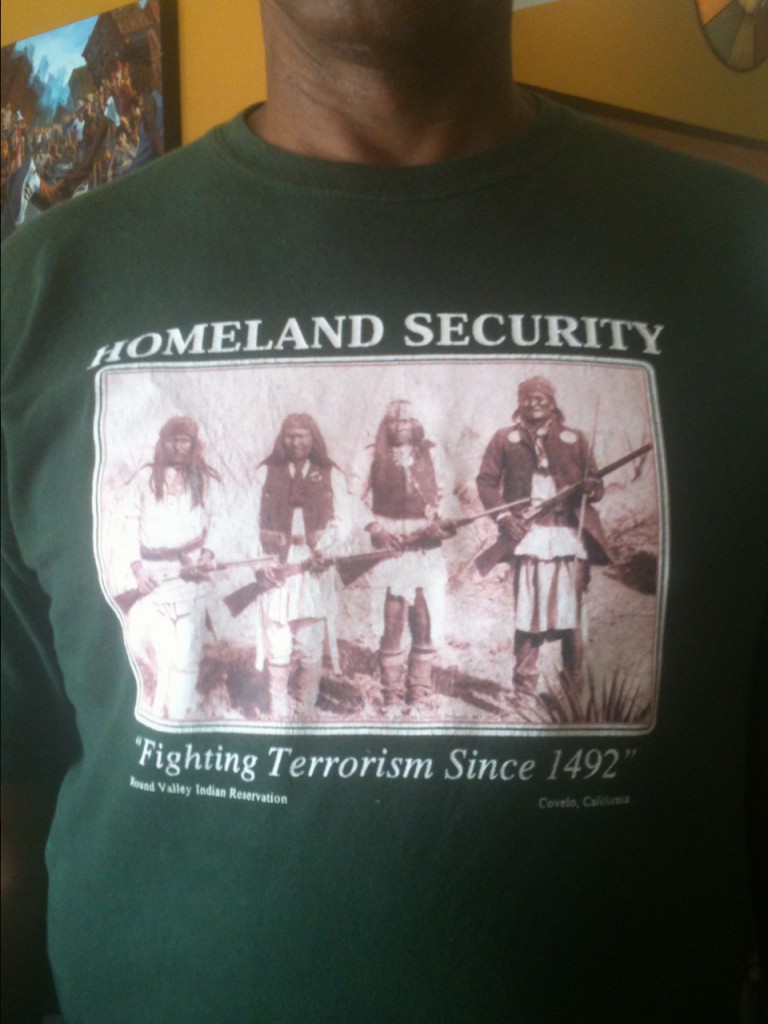

I just read the Michael Brown post [by Uzma Z. Rizvi] while in a Black hair salon in East Oakland, where my African friend is getting her hair done (behold: transnationalism, diaspora!). I found the shirt pictured [above], worn by an older Black man exiting the salon, poignant in light of the article mentioning the Department of Homeland Security, and Prof. Rizvi’s statement about the inescapablity of being judged on the color of one’s skin. I wonder how many White anthropologists, reading what Prof. Rizvi has written about racism and the absence of benefitting from White privilege, are really willing to reckon with the implications of this admission, or care about the deep pain of racism they know they will never experience, especially in relation to racial profiling and brutalization by police–which as Prof. Rizvi rightly notes, occurs, especially to bodies coded Black, regardless of education and class (though low socio-economic status clearly exacerbates such racist encounters and outcomes).

In particular, I am struck by what Prof. Rizvi writes about the cultural character of resistance in the US, a theme which is worth problematizing in relation to the aforementioned shirt, pictured above.

I thank Prof. Rizvi for showing sincere solidarity with Michael Brown’s family, the residents of Ferguson, and Black Americans in general, as this statement of solidarity–within an acknowledgement of enduring anti-Black racism (versus an attempt to minimize or deny it) is something far too many anthropologists (i.e. White anthropologists) do not do, especially in relation to being honest about how often anthropologists share the very same anti-Black biases which make the murder of Black boys/men like Michael Brown and Trayvon Martin, and Black girls/women like Renisha McBride possible–as well as the criminalization of Black people simply because of enduring stereotypes of Black people as violent subhuman animals and savages (as Dick Powis discussed in his response to Matt Thompson’s post on what constitutes a riot). In short, the slaying of Michael Brown did not occur in a vacuum: it is the product of larger structural inequalities and implicit biases which also exist in and are (re)produced by the academy.

The sad reality, as I have personally witnessed and experienced first-hand, is that many (non-Black, and especially White) anthropologists have extremely negative views of Black people overall, even as the discipline officially claims to be antiracist and rejoices, in self-congratulatory fashion, in publicly excoriating Nicholas Wade and identifying only the most blatant and explicit enunciations of racial inferiority and racial animus as ‘racism’ and ‘racist’ and ‘white supremacist’.

But what happened to Michael Brown, is also about White supremacy, including everyday practices that all anthropologists participate in which normalize devaluing Black lives and seeing Black people, especially the darker-skinned they are, as less human, less intelligent, more violent and criminally-inclined. (Yes, the Savage Slot persists.)

It is not just Prof. Rizvi’s students who are blind to ‘quotidian racism’. Plenty of (White) anthropologists are also blind to these ‘everyday practices of White supremacy’ (such that calling out behavior or individuals as ‘racist’ and ‘white supremacist’ comes to be misrecognized as being ‘mean-spirited’, because forthright critique of such everyday practices of White supremacy in the US happens far too little in Anthropology and is rarely the subject of anthropological ethnographies). The ability of so many of the author’s White students to believe we live in a postracial world, and their inability to be clued in to the racism people of color constantly face, regardless of class or education, is very much a product of Anthropology’s own ‘race avoidance’ as discussed in “Anthropology as White Public Space?”: ‘We’ don’t really write the books, articles, ethnographies about daily racism in the US, about daily manifestations of White power and privilege that would (re)educate these students, or ‘the public’ more broadly. (Public Anthropology?)

So I applaud the genuine solidarity and antiracism education in which Prof. Rizvi is engaged. I just wish more anthropologists were doing this work. And forcing a conversation on the implicit (anti-Black) biases of anthropologists themselves, as well as the daily practices of White supremacy and anti-Black racism which are a part of academic life, just as they are a part of American life more broadly. And please note that I did not write ‘US life’ because this issue of anti-Blackness, White supremacy, and racial control of people of color via (militarized) policing is not limited to the US, but is characteristic of ALL the ‘post-slavery’ states in the Americas. (Yes, buzzwords/themes like ‘globalization’ and ‘transnationalism’, which anthropologists usually like.) The issue is the ongoing legacy of racialized slavery, genocide, and dispossession in the Americas, and the racial logics of humanity and sub-/non-humanity with which we continue to live, and die, such that some people–like Michael Brown, by virtue of his Blackness–are always already seen as disposable non-persons, bare life, and those who Anthropology has long spoken for while often refusing to listen to as equals.

So yes, returning, recursively, to the shirt/photo above, it is worth thinking about the issue of resistance, raised by the author in the post. Whose resistance is even recognized as a political act in the first place, and whose is instead seen as the dangerous rioting/violence of subhuman animals who must be controlled and silenced, by any means necessary? Moreover, the anger currently being expressed by Black people and Black communities is a thoroughly anthropological issue: as anthropologist Catherine Lutz reminds us in her book Unnatural Sentiments, “emotion is an index of social relation”. Constantly denying Black people, especially poor and working-class Black people, our right to anger over being constantly dehumanized as nothing more than violent animals against whom the police and others/society must defend itself (yes, this is a conscious Foucault reference) is dehumanization in and of itself, reinstating the very racist logics that Nicholas Wade advocates about Black people as constitutionally less intelligent and more violent. This is exactly the racism that anthropologists claim they repudiate and do not want to support. When will our words match our actions?

Post-Script: I wrote this comment before reading Brittany Cooper’s In Defense of Black Rage, over at Salon. In it she articulates many of the same points I have articulated here and elsewhere, for years, often to be met with some version of ‘shut up and stop complaining about your “personal issues” no one cares about or racist abuse I am not going to believe’. Such a response is easy to give when you will never be on the receiving end of racial profiling and police brutality, and when the pain of racial discrimination is only an abstract concept and not an embodied experience. I think what is most important about both Prof. Cooper’s post, as well as Prof. Rizvi’s is, their willingness to acknowledge the real pain that racism causes those who have to endure it, suffering which those who don’t have to experience (anti-Black) racism all too often neither want to hear about or believe. In particular, I want to draw attention to what Prof. Cooper says about how Black rage scares White people. (But why would anthropologists, or anyone else, expect black people to be alright with being dehumanized, seen as animals, and treated as second-class citizens if human beings at all? Why should such racism produce something other than anger/outrage? And shouldn’t anthropological empathy be capable of understanding such anger, instead of summarily dismissing, pathologizing, and silencing it? If the good ethnographer can have sympathy for Nazis, why not Black anger too?) But Coopers’s discussion of why Whites fear Black anger is one I have found few White anthropologists willing to have. Why?

It is easy to talk about racism when it is displaced onto others. This is one reason it is so attractive for anthropologists to excoriate Nicholas Wade. But it is much harder to talk about the racism that involves ‘us’, admit to the fears Brittany Cooper writes about, admit how and why (White) anthropologists have them too, and admit the kinds if life-endangering, brutalizing abuse and dehumanization such racism makes possible – yes, even from anthropologists who believe themselves to be ‘past racism’. If anthropologists, as a discipline, truly want to be engaged in an antiracist project contra people like Nicholas Wade, they, too, will have to be honest about the fear/anti-Blackness of which Brittany Cooper writes – however uncomfortable and difficult looking in the proverbial mirror may be.

This is a wonderfully thoughtful essay, but being a Shawnee woman who is also an anthropologist, I keep coming back to the shirt. It is perplexing to me that even in this context the image of Native people is used while simultaneously excluding Native realities from the discussion. Perhaps more problematic is that shirts and bumper stickers bearing these kinds images — this one in particular — are very often used to advance anti-Muslim, anti-immigrant, pro-gun narratives by organizations and individuals who give little to no thought to indigenous people outside of an attachment to the trope of the Noble Savage. (Cliven Bundy and his ilk come to mind.) So when I see shirts like this, what I see is an extension of historical trauma. Indigenous bodies and histories are routinely decontextualized and commodified by the colonial empire, used in service to romantic nationalism, and willfully ignorant to the inherent irony embedded within: that these “defenders” and their actions were not seen as proud and courageous at all but instead as vain attempts by backward subhumans fighting on the wrong side Manifest Destiny.

Thank you for your feedback. I am sorry that I did not foreground the Native connection more explicitly, though this is actually what incas referring to in using the term racialized dispossession and genocide, while commenting on a shirt that frames homeland security and resistance in the Americas as beginning in 1492. I was trying to link the present violence in the Ferguson to a larger history of racialized violence coming out of colonial subjugation. Sorry that this wasn’t more clear, and sorry for any pain using the photo caused.

Also, I and the man wearing the shirt had a conversation about the shirt in advance of my taking the picture, which I asked his permission to take. I first said, I appreciate the shirt in light of the protest occurring in Ferguson. We talked about how the shirt was about a larger struggle for resistance against White supremacy and the ongoing legacy of colonialism in the US, which began with stealing land from Native peoples. He commented on how many White people ‘didn’t get’ the shirt, or why he wears it. He both laughed wearily. That’s when I asked to take his picture and decided to comment on Prof. Rivzi’s article, which was quickly written from my phone while waiting for my friend. This is the context for why I wrote what I did, and used the shirt to think about the enduring legacy of colonialism in the Americas. I am now sorry that I was not more explicit about this back story given that I wanted to discuss the shirt as a way of thinking about antiracist solidarity, not to have it be the source of more trauma for Native people, or engage in a rumination on racism in the Americas which erases them.

This week I have also been talking a lot about the racialized dehumanization of Palestinians in Gaza, and how both Israel and the US are settler societies practicing settler colonialism, so your response about erasing Native people is much appreciated, since this is exactly what I do not want to do.

I hope that by having these conversations we can challenge the discourses of subhumanity with which we continue to live and suffer.

Thank you for your clarification and I hope it’s understood that my comments are not intended to take away from or indicate any lack of support for the post or its content. Being mindful of the community standards, I don’t wish to talk too much about my own work, but it is very concerned with how these kinds of images are used in a very uncontested way at all levels of society. This is possible in that the reality of Native lives is so muted, having a trickle-down effect on the way we as Native people see ourselves and/or interact with others because of the constrained ways in which they see and understand us. This type of microagression is worth thinking about because it is so normalized within (but not limited to) American culture and because forums in which Native people can raise these issues are themselves so limited. No one even notices! Dustin Tahmahkera’s fine article, “Custer’s Last Sitcom,” and its concept of “decolonized viewing” so changed me that even beyond the knee-jerk reactions I have to representations of Native people, I now find it impossible to consume them without a deeply critical eye. And I am glad of that.

Thank you for writing this post. I am not an anthropologist. I am a cultural food geographer, but I think that it is very similar to anthropology in terms of this discipline as being historically part of the European and USAmerican colonial/imperialist projects.

This article is timely, as I am working on a new book about decolonizing the diet, as practiced through certain black male vegans and vegetarians engaged in hip hop methodologies. I literally am starting the introduction to the book by talking about how one must acknowledge that ‘decolonizing the diet’ must be be understood within the context of systemic violence against Black men. I am writing about about Trayvon Martin, Oscar Grant, and now Michael Brown to give context. But, I also began thinking about how I haven’t really heard this particular focus (i.e. the meaning of these men’s deaths and its influence on critical geographies of food) in my discipline. The focus on alternative food ways and ethical food systems continues to be uncritically informed by post-racialness, for the most part. Peter Singer, J Salatin, and Michael Pollan, for instance, are what I get my mostly white colleagues referring to when they tell me about ethical eating. Read the mainstream bestselling titles and internet sites and you will not come across how the prison industrial complex, racial profiling, anti-black male thinking directly impact ethical food philosophies and practices; and these topics are certainly not central to food studies. I often feel like I am only having a conversation with myself; that one need not be concerned with the significance of my research because it’s ‘too much on the margins’ and has ‘nothing’ to do with the [fantasy] world of white slow food ethical movement that so much of food studies is dedicated to. I am also deeply engaged in vegan and animal rights studies, as related to food culture. I have brought up many times to my mostly white colleagues that the locations of some of the vegan and/or animal rights events give me concern in a way that they don’t have to think about these things. For example, “Hey, I just checked out this event’s location and it’s in what I’d consider a historically sundown down. Should I as a black woman be there?” or “What do we do about the person of color who was trying to get to this event and was racially profiled by the police?” I think the lack of mindfulness around these valid concerns isn’t about being consciously white supremacist. It just really reveals how white people’s relationship to non-racial-violence towards them (hope that makes sense) impacts how they think about food and ethical eating, including where to hold events and what to discuss during this events.

I am not sure why awareness around the issues you bring up are missing from anthro as well as many other disciplines. It’s not just academe; it reflects mainstream USA. I can’t tell you how many times my social science based inquiries into whiteness and ‘fear of blackness’ were conveniently interpreted as me being hostile, or mean, or ‘distracting.’ It didn’t matter if I had a PhD in it, won honors for the work I did, published a lot…. my inquiries were reduced to me being an emotional and angry black woman who is being ‘nasty’ to ‘well-meaning’ white people who are not racist. It is these responses that keep my going with my work.

Thank you for writing your article.

Correction: Mean to say “sundown town” not “sundown down”.

Dear Kerry,

First, I hope it is alright that I addressed you by your first name, but please correct me if it’s not. No, I did not feel your comments in any way detracted from my post. Quite the opposite. I am glad you shared your perspective and raised an issue we all need to think about.

Thank you for the feedback!

In light of this Jacobin analysis of the events in Ferguson (https://www.jacobinmag.com/2014/08/itemizing-atrocity/), I want to return to your comments Kerry, and address an issue I had been thinking about raising in my previous response but did not, especially because of some people’s fondness in saying that such a response constitutes an ‘oppression Olympics’, and I just didn’t want to deal with this abuse. But as the Jacobin article and Julianne Hing’s Colorlines post on Asian American responses to Ferguson make clear, the issue of racial hierarchy needs to be raised.

I again want to emphasize that I do not want to cause the kind of pain or objectification or marginalization of. Native people that your comment was right to draw attention to, but I also want to recuperate the value of the shirt/photo and why this Black man was wearing it and we both identified with the sentiment of resistance to US/American state-sponsored White supremacy that the shirt articulates by bringing together the photo with the shirt’s text. The Jacobin article makes this connection, the same one I was thinking about, more explicit, especially in explicitly stating that recent, post-9/11 response to the ‘war on terror’–like the Department of Homeland Security and militarized police response of the kind presently occurring in Ferguson–are not in fact new for Black people (or Native people) because the ‘war on terror’ has always already been here for us. And my parenthetical bracketing of Native people is not to marginalize them yet again, but an admission that the Jacobin article specifically focusing on how the current militarized policing we are seeing is not simply the function of a recent ‘war on terror’, but is the function of policing in this country that arises out of anti-Blackness and post-Civil War slave patrols (a fact most SM readers are probably not aware of, and an ignorance which allows people to make claims about how we can ‘suspend race’ at the times when it should be most analyzed).

You are absolutely right to worry about how Native people and images of them are perceived and used. Absolutely. But in the case of this shirt and why many Black people identify with it, especially now, I also think something else other than marginalization and unfair appropriation is occurring: a deep,embodied understanding of resistance to racism and White supremacy in the Americas that understands that for some of us, in the US/Americas, the ‘war and terror’ did not begin on September 11, 2001, but in 1492.

I think the power, or at least the potential positive and anti-racist power, of this shirt is in understanding how this shirt, and the resistance it visibilizes, is an opportunity for antiracist solidarity–but only if we are honest about the kinds of racial hierarchies that we live with. So, I as a Black person (especially as the daughter of African immigrant parents) have to acknowledge that I am a settler living in not only a racial state but also a settler society that still de facto colonizes Native peoples, even as it claims to be a post-colony. Likewise when we talk about the ‘war on terror’ already have been here in relation to militarized police responses that make onlookers see Ferguson as ‘like Gaza, like Iraq’, we have to be honest about the specific role anti-Blackness plays in this racist social control. This latter admission is not about marginalizing Native peoples, just as acknowledging that Black people are also de facto settlers is not about diminishing the reality and persistence of anti-Blackness. And things become even more complicated, and imbricated, when we start talking about how the categories Black and Native are not mutually exclusive given the history of ‘race mixing’ in the Americas. So yes, this is about a shared history of racialized dispossession and genocide stretching back to 1492, even as there are differences.

What I saw in a Black man wearing the shirt pictured above was the two most brutalizing ways in which the ‘war on terror’ has always been here on American soil, as embodied by the struggles of Native Americans and Black people who were constructed as less-than-fully-human so as to justify killing them with impunity, stealing land, and enslaving human beings who were not seen as such.

I’m reminded of the myopia of American and of academic politics. Uzma Z. Rizvi is at Pratt, an overpriced school for the wealthy. And then there’s Sharjah. A friend of mine jokes about the Sharjah Biennial and the estheticized leftism of the petulant children of the ruling class. “Discuss White Privilege” strikes me as a woman who’s made a career out of explaining the racism of liberal white people to liberal white people; kept around because her presence assuages their guilt. The obvious parallel is the silent acceptance of Israeli policies by guilty Goyim. And in the end both DWP and Israel are non-threatening, to whites.

My twitter feed is full of expressions of solidarity by Palestinians with the people of Ferguson, but not much the other way around. I wouldn’t expect otherwise; the working class around the world knows more about Ferguson than Furguson knows about the world. A bubble economy is a ghetto economy. A moral and intellectual bubble economy is a moral and intellectual ghetto economy. That applies to Ferguson or Versailles in 1789, or Yale.

Ferguson is a majority black community with a white Republican mayor. The people in Ferguson are fighting their own apathy as much as they’re fighting white racism. Apathy is less of a problem in the West Bank and Gaza.

Another thing that’s been annoying are the claims among angry vanguardists that Ferguson reminds them of OWS. The most productive comparison would be the protests in Wisconsin in 2011. That’s what needs to be built on, from the ground up not the top down or from the vanguard to the rear.