[This is an invited post by Greta Uehling. Greta is the author of Beyond Memory: The Crimean Tatar Deportation and Return published by Palgrave Macmillan in 2004 as well as a number of articles on the Crimean Tatars. She teaches in the Program on International Studies at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor.]

As pundits, politicians, and the world’s media wring their hands over Putin’s next move, events in Crimea seem to be fading from attention. Residents of Crimea have noted, correctly I think, that even after annexation, the Autonomous Republic of Crimea remained little more than a square on the board of a geopolitical chess game.

Focusing my attention on that square, the tiny, green, diamond-shaped peninsula hanging in the Black Sea, has been distressing to me over the past weeks. I have conducted anthropological fieldwork in Crimea on and off for almost two decades. Most recently, I have been using Skype calls with friends and colleagues on the peninsula, as well as local television available on the internet, for information. When the annexation took place, I was in the early stages of a research project exploring the groups’ overlapping and yet competing idioms of belonging on the peninsula they share. Memory and history have complicated concerted efforts to build a peaceful and tolerant society. My discomfort started when a Skype message came in early one morning from my friend Sabrie: “Good morning, dear Greta we are really popular all over the world right now, but frankly they don’t understand what is going on.”

What is it that we don’t yet understand? Can the lived realities of the annexation help us grasp the full implications of such a sudden geopolitical change?

From the Crimean perspective, the recent occupation and annexation is viewed through the lens of the last one, which occurred when Nazi forces rolled in and occupied the peninsula for close to four years. The Crimea they occupied, I am told, was an ethnically and linguistically mixed and tolerant one, in which people spoke each other’s languages and lived lives that were intertwined at the everyday level. That occupation pulled some residents to the German side, others to the Soviet side, while still others changed sides multiple times. The exigencies of survival cast a shadow over the peninsula that is with Crimeans today in the form of mutual suspicion and distrust. Now the peoples of the Crimean peninsula are again experiencing a liminal space of law.

Events in Crimea resonate with Agamben’s description in State of Exception, which examines our evolving legal-political culture and suggests the existence of a realm of activity not subject to law. In Agamben’s view, a “state of exception” comes about when law is temporarily suspended, or when the only law that applies is that of the sovereign itself (Agamben 2005:34). Sergey Aksyonov, known in the criminal underworld as “the Goblin,” is a paradigmatic example of the sovereign as an exception: after his mercurial rise from cigarette dealer to Prime Minister, he is uniquely privileged by the law to suspend the law and rule by personal decision. The Wikipedia page in his name alludes to this paradox stating he is a wanted man: “Since March 5, 2014, he has been wanted by the Ukrainian Security Service, after being charged under Part 1 of Article 109 of the Criminal Code of Ukraine (“Actions aimed at the violent overthrow, change of constitutional order, or the seizure of state power”). The Russian occupation of Crimea was simply not supported by reference to any international law, international norms, or interstate agreements. Now, Crimean lawmakers and politicians are working around the clock to establish a new political order on the peninsula.

But we can’t go so far as to assume the suspension of law. In a counterpoint to Agamben, John Comaroff and Jean Comaroff (2006) have noted that rather than the suspension of law, discourses of legality, accompanied by discussion of new rights, new laws, and new constitutions are multiplying. The idea of a state of exception is intriguing, however, from the perspective of a spectacle of law in which local leaders attempt to inspire confidence by pointing to the visits of outside “experts” in order to reassure the frightened public about the more or less immediate passage of a new constitution by the new office holders. We also see the proliferation of horizontal and parallel sovereignties as the Crimean Tatar national assembly, the Quraltay, and its executive body, the Mejlis, confront a Catch 22 regarding whether or not to engage with the new authorities. As the Comaroffs point out, a proliferation of laws should not be understood as a sign of order.

Indeed, throughout the tragicomic occupation, Crimea was overrun and “ruled” by unidentified masked and armed men referred to sarcastically as “little green men.” As a popular journalist and talk show host, Liliya Budjurova phrased it, “We live in a time when the law has become a joke. Invoking the law is laughable when it is in the hands of anyone who holds an automatic.”1

Following the so-called referendum, Crimean political scientist Alime Absilam told Budjurova that there is no reasonable explanation for how or why events unfolded as they did – only the idea of chaos really applies. “The situation can’t be explained in term of reasonable facts, reasonable needs, reasonable motivations, or reasonableness. A reasonable person can’t say it ‘yes, it happened because there is a link between cause and effect.’”1 When Crimeans feel they have lived through a political “volcano,” in this liminal space of law, cause and effect no longer appear connected.

From the perspective of the indigenous people looking at the international system, political culture appears bereft. In spite of verbal condemnation and written declarations and resolutions, there seem to be no truly working international mechanisms that can be used to roll back the Russian incursion into the peninsula. The idea that “We have been left alone with our problems” is therefore a common theme.

The liminality is not only legal and political, but personal. Many familiar referents have been suspended: clocks are being changed by two hours (so Crimea is aligned to Moscow time), the official currency has been changed to the ruble (which is in notably short supply), banks and cash machines are closed, Crimean Tatars are being told by some residents they can’t speak their native language (supposedly one of the official languages) and Crimeans will now need new, Russian passports to navigate their post-Ukrainian reality.

The calm, indeed the “warm welcome” Peter Kenyon referred to while reporting on Morning Edition is decidedly Goffmanesque. As a local Ukrainian opined when probed by Budjurova about the calm in the face of these changes: “Yes, but it’s a performance of calm. It’s a performance on the part of politicians, imported actors, and masked members of the occupying forces.” Whether (or perhaps when) this frame of public calm will be broken is an important question.

Further from the capitol, it’s already clear that the front stage, ritualistic, impression management of calm in public is inconsistent with backstage anxiety: windows are boarded up; children are kept home from school, and Crimeans report not only being too anxious to eat, but sleeping in their clothes. Some Crimeans have taken to placing metal pipes or poles the rooms of their house in case they need to defend themselves, a natural reaction to men in ski masks patrolling the streets with baseball bats in one hand, and lists of addresses in the other. So while the annexation of Crimea is slowly being normalized in Europe and the United States, routine has been profoundly ruptured in Crimea.

It would be deeply unfortunate if the international community lets go of Crimea while focusing on eastern Ukraine. Agamben suggests the encroachment of states of exception warrants more sustained attention because it translates into the gradual shrinking of space for meaningful political action. I find this a compelling argument whether or not the spread and increase in the number of states of exception around the world is an empirical reality (Rigi 2012).

Residents of Crimea are living through an extremely challenging time. Just as the Crimean Tatars’ homes were marked prior to the deportation ordered for early dawn by Stalin almost exactly 70 years ago, crosses have recently been scratched into Crimean Tatar doors, and neighbors are reported to be plotting how they will divide up property after the Crimean Tatars leave or are removed. Even if these are tactics to psychologically intimidate, they represent a deeply troubling rollback of ethnic tolerance. The chaotic political landscape and evaporation of tolerance has sent some residents packing. Several Crimean Tatar friends have written panic-filled emails asking “where can we find refuge?”

The passage of laws recognizing the Crimean Tatars as an indigenous people at first appeared promising. However, because they view this through the lens of the 1944 deportation that resulted in catastrophic loss, the indigenous Tatars draw parallels between this situation and others in which legal provisions of this nature provided authorities with a way to claim they did everything they could before disappearances and killing started.

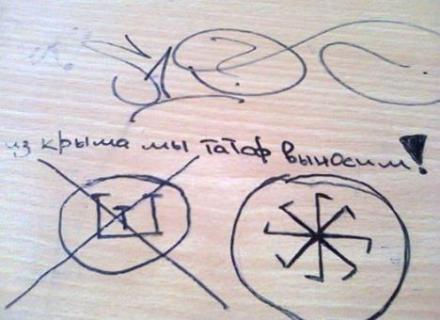

And killing, beating, and hate speech have started: a Crimean Tatar who protested the occupation, Reshat Ametov was disappeared, possibly tortured, and killed. A fourteen year old boy was beaten up after local youths overheard him speaking his native language. And an act that hopefully does not become more widespread, a warning scrawled on the desk of a Crimean Tatar student states “We’ll take the Tatars out of Crimea.”

The reverberations of this annexation, like the Nazi occupation, will be with us for many years to come. It is essential we understand the lived realities associated with annexation, so we may grasp the full implications of such a sudden geopolitical change.

Bibliography

Agamben, Giorgio. 2005. State of Exception. Trans. Kevin Attell. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Comaroff, John L. and Jean. 2006. “Law and Disorder in the Postcolony: An Introduction,” Law and Disorder in the Postcolony, Jean Comaroff and John L. Comaroff eds. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Rigi, Jakob 2012 “The Corrupt State of Exception: Agamben in the Light of Putin,” Social Analysis. Vol 56(3) Winter 2012, 69-88.

0 thoughts on “Memory, History, and Xenophobia in Crimea”