[This post is part of a series featuring interviews with designers reflecting on anthropology and design.]

DANIELA ROSNER. design researcher. ethnographer. science studies scholar.

ANTHROPOLOGY + DESIGN.

I think design and anthropology have the potential to reinforce each other’s aims. Anthropology could help develop a more socially informed design process, and design could help clarify anthropological investigation. That’s the goal, but not always the end—design can over-simply or misinterpret anthropological insights, and anthropological inquiry can overdetermine or stifle design. What’s helpful in an anthropological interpretation of design is how it helps reveal an instance of design as just one (of many) located and specific moments of change. Lucy Suchman articulates this nicely in her writing on the limits of design, suggesting that “conventional design methods are (necessarily) silent on matters that anthropology would be interested in articulating” (2011:3).

Conversely, design can open up creative possibilities overlooked by other modes of investigation, and help anthropologists communicate in the field. For me, design often involves studio-based explorations. Design can take on many forms for different people, but as someone with an undergraduate degree from the Rhode Island School of Design, I base my own methods on those early days—thinking with materials and building intuition through hands-on explorations.

WHY NOW.

The pace and form of design and technology development has radically changed in recent years, and anthropological methods can offer fresh insight into the cultural stakes of these transformations. For example, anthropology can help explain how and why small-scale, device-level design activities get connected to broader social changes relating to STEM education, green computing, or institutional frameworks and policies. Making anthropology more explicit in the work of design could help designers reach beyond their areas of expertise to ask questions about the cultural, political, and ethical implications of their work.

WHAT I DO.

Design can serve anthropology in multiple ways, but I see three as central: interventions, responses, and extensions.

By interventions I’m referring to the kinds of designed objects, systems, or programs that enable anthropologists to ask questions about a field site. Such interventions might involve deploying cultural probes, as Gaver and others have done (Gaver, et al. 1999). For me, interventions have entailed extended provocations that suggest ways of reimagining commonplace practices such as knitting (see Tony Dunne and Fiona Raby’s writing on speculative and critical design, 2013). While conducting participant observation in a knitting guild, for example, I introduced a tool that I developed called Spyn that enables people to annotate their hand knit products with digital messages and geographic locations (Rosner & Ryokai 2012). Introducing the technology not only revealed something about the technology itself—that it could be used to turn knit artifacts into puzzles, travel journals, and mix tapes—but it also told me something about the knitting worlds I had entered: that members of this guild saw themselves as outside an engineering culture that threatened their social organization, and even their moral order.

Now by responses I mean something very different. I’m talking about the kinds of designed artifacts that come out of a careful investigation of a field site. For example, activist projects that enact argument and prompt social change in response to ongoing fieldwork. This could involve building a website like Turkopticon in response to asking “crowd workers” to describe a hypothetical Bill of Rights on Amazon’s Mechanical Turk, as Lilly Irani and Six Silberman have done. Or it could entail curating an exhibition, as I did last spring at the Oakland Museum of California with female artists working with broken materials, from e-waste to torn clothing. I gathered the artists in response to the shifting gender dynamics I observed while working with hobbyist fixer groups over the past year.

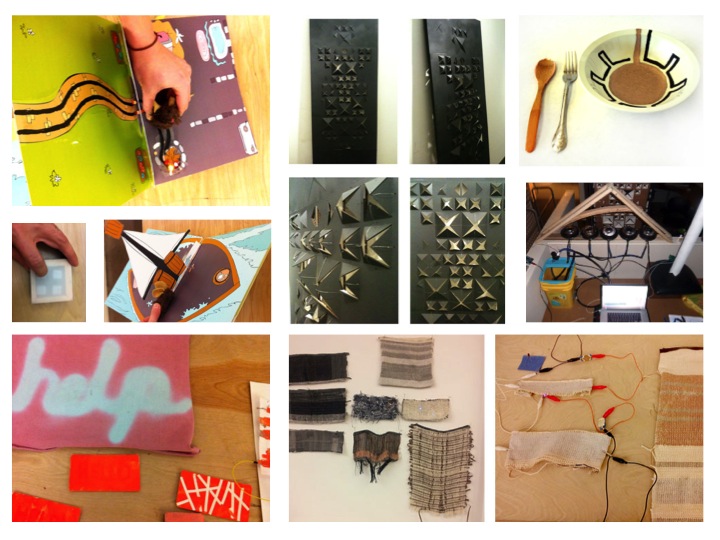

Lastly, by extensions I mean design projects that embody and extend the forms of value, engagement, and practice embedded in the sites we study. This work invites a wide range of material engagements. While looking at relations between the “maker movement” and Stanford’s program in design last year, I worked with a team of students at Stanford University to develop a Playdough and soft materials 3D printer for children called Fingerprint. As a participant and observer on this design team, I found the soft materials printer reflected the particular ways members of these groups conceptualized technology for making, revealing making as shared ideological work (Berger 2003). With my students at the California College of the Arts, we used hands-on explorations with ordinary and extraordinary materials—from piezoresistive fabrics to leather and wood—to trace and extend object histories (Rosner, et al. 2013). Most recently, in my group at the University of Washington, the Tactile and Tactical Design Lab, we have been looking at feminist constructions of hacking in local hackerspaces (community-operated co-working spaces) through a set of “Critical Design” workshops. Sarah Fox and Rachel Ulgado, two PhD students I work with, have been exploring just how feminist perspectives get entangled with members’ conceptions of design to collaboratively build environments that embody members’ hopes and concerns for the future.

In sum, these approaches are not fixed or exclusive approaches, for they often overlap and intertwine. Instead, I’ve found them useful as guides for finding my way across new or unfamiliar interdisciplinary lands.

ME.

Daniela K. Rosner is an Assistant Professor of Engineering at the University of Washington and co-director of the Tactile and Tactical Design Lab (TAT lab). Through fieldwork and design, her research reveals and creates surprising connections between technology and handwork. This work results in new theoretical frameworks and interactive systems for the practices and spaces of design and repair. She has taught interaction design at the California College of the Arts (CCA) and worked in museum exhibition design, most recently at the Adler Planetarium and Astronomy Museum. She holds a Ph.D. from UC Berkeley’s School of Information, a M.S. in Computer Science from the University of Chicago, and a B.F.A. from the Rhode Island School of Design in Graphic Design. Daniela is a regular columnist for Interactions Magazine, a bimonthly publication of ACM SIGCHI.

RESOURCES.

Berger, Bennett M. 2003. The Survival of a Counterculture: Ideological Work and Everyday Life Among Rural Communards. Transaction Publishers.

Dunne, Anthony, and Fiona Raby. 2013. Speculative Everything: Design, Fiction, and Social Dreaming. MIT Press.

Gaver, Bill, Tony Dunne, and Elena Pacenti.1999. Design: Cultural Probes. Interactions 6(1): 21-29.

Rosner, Daniela K., Miwa Ikemiya, Diana Kim, and Kristin Koch. 2013. Designing with Traces. In Human Factors in Computing Systems. Paper presented at the Association for Computing Machinery Conference. 1649-1658.

Rosner, Daniela K. 2014. Making Citizens, Reassembling Devices: On Gender and the Development of Contemporary Public Sites of Repair in Northern California. Public Culture 26(1 72): 51-77.

Rosner, Daniela K., and Kimiko Ryokai. 2009. Reflections on Craft: Probing the Creative Process of Everyday Knitters. Creativity and Cognition. Paper presented at the Association for Computing Machinery Conference. 195-204.

Suchman, Lucy. 2011. Anthropological Relocations and the Limits of Design. Annual Review of Anthropology 40: 1-18.

Daniela,

In The Ten Faces of Innovation, Tom Kelley writes,

The Anthropologist is rarely stationary. Rather, this is the person who ventures into the field to observe how people interact with products, services, and experiences in order to come up with new innovations. The Anthropologist is extremely good at reframing a problem in a new way, humanizing the scientific method to apply it to daily life. Anthropologists share such distinguishing characteristics as the wisdom to observe with a truly open mind; empathy; intuition; the ability to “see” things that have gone unnoticed; a tendency to keep running lists of innovative concepts worth emulating and problems that need solving; and a way of seeking inspiration in unusual places.

Is this how you. or other designers, see the role of the anthropologist in design?

Pictures aren’t showing