[The post below was contributed by guest blogger Deepa S. Reddy, and is part of a series on the relationship between academic precarity and the production of ethnography, introduced here. Read Deepa’s previous posts: post 1 — post 2 — post3]

Note: updated on 7/26/2012 for clarity.

For this final post in our series, I find myself returning to Carole McGranahan’s post from some weeks ago, going through her very useful 9-point schema to describe what makes things ethnographic these days—realizing that whatever the circumstances of ethnographic production, whatever our definitions of ethnography might be, they always presume the centrality of writing. And that is writing in a particular mould, one that satisfies most, if not all, of the criteria enumerated in McGranahan’s post. Specialized, often lengthy, mono-graphs or variants thereof.

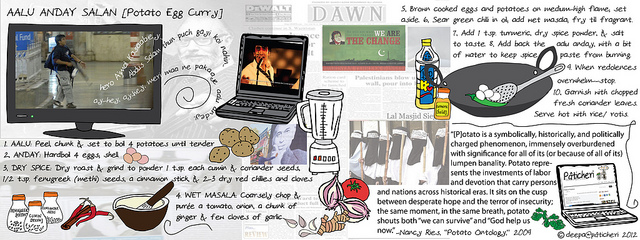

Recipe for Pakistani-style Political Potatoes

Recipe for Pakistani-style Political Potatoes

[Click on the image for a more readable higher-res version]

Part of me wants to say: But of course, how could it be otherwise? The other part, perhaps handicapped by my present need to cobble together a professional identity while remaking myself in an almost completely new cultural landscape—and finding precious little time to devote to writing, is wondering about ethnographic end-products, and the centrality of conventional writing to the ethnographic enterprise. In this post, therefore, I’d like to think through the prospect of decentering writing [fully aware that writing can’t ever be entirely displaced; that there is an awkwardness to the idea, reflected in this post’s two-ing title].

Think for a moment about the text I’ve helped to draft for the website of the NGO on whose board I serve. Would that count in some measure as ethnography? There’s history there, some of it detailed, rationale and argument at least for work undertaken, there’s analysis of failure and success, there’s certainly the attempt to articulate native points of view (an appreciation, in fact, of how villagers in the surrounding regions of Pondicherry talk back to social workers, government representatives and others claiming to have the solutions to their problems), there’re individual named people, a focus on ethnographic realities, on life lived; it’s a narrative in clear dialog with issues of pressing local concern. It’s all instrumentalized, yes, but so also was HapMap (my prior research investigating Indian views on genetics for the International HapMap Project), and so really is just about all research if it’s used as a means to career advancement.

But then again: there’s no theory, no. There’s no argument per se—but for a sometimes explicit, sometimes implicit appeal to donors. There’s no reflection on how knowledge was amassed (it’s the work of the organization, after all). And there’s no effort at all to establish the credibility or credentials of the author—in fact, there’s no one person who is formally assigned authorship. I’m not in that project as an ethnographer.

For these reasons, I retain a sense that the work done for the NGO represents something not-quite-ethnographic. But wait. Might it not be possible to think of it as ethnography that is—if I may hearken back to James Clifford’s words from Writing Culture and twist them just so slightly—partial: committed and incomplete?

After all, whoever said it was necessary to find all elements of ethnography only in one place? Our conventional outputs are sites of collection: empirical data, theories, history, context, analysis, critique are all present, and rolled together, ideally coherently. Writing seems inevitable, yes; for many of us, it’s a habit we(‘ve come to) love. But do we really have to do it all in our final outputs? Could it count as ethnography if we didn’t? What if we were to rethink the commitment we have to the “ethnographic monograph as the singular product of merit,” as Lane puts it?

I’ve been suggesting all along that conditions of precarity lead to a cobbling together of what’s available and what’s possible, making ethnographic virtue out of circumstances such as they are. To some extent, I presume this is true of all research—that it’s itself such a process of cobbling-together, and working with the data that is, rather than with the data that ideally should be. The sorts of research questions that can be asked are necessarily curtailed by circumstances; I suspect we all work all the time with stop-gaps and bypasses of one sort or other. [Cori Hayden’s When Nature Goes Public, for all its dense prose, is useful in explicating this aspect of contemporary research realities.]

Now although we acknowledge this reality of research, the point is that the cobbling and corralling of “ethnography” isn’t otherwise really reflected in much of the (specialized) writing we do produce. The “conference paper” reflects the process rather more at times, but then again we expect that because it is, almost by definition, a work in progress. What would it mean to think of conference papers, or the commissioned video ethnographies of which Laurel wrote or breathing practice (Ali’s post) or observational practice (Lane’s) as attuned ways of seeking, comprehending, analyzing that are the here-more-personal there-more-public but always full-fledged ethnographic products? How would such a re-thinking change how, what, for what audience, and indeed how much we write?

Briefly, I’d like to consider the work of blogging. I cannot exactly start in here on what blog writing has done to ethnographic writing; there’s much more to be said about the use of such formats in research and teaching than what I can cover in this post. I’d like to propose, however, that the open-endedness of the blog and the conversational space it opens up is almost perfectly suited to the sort of corralling and cobbling of “ethnography” that I find myself consistently undertaking—especially in the absence of the means or the time to more comprehensively study cultural phenomena. I hear increasingly from colleagues that blogging is now considered industry good practice to promote one’s own research or upcoming book. There’s research and discussion on using blogging as a means to fieldwork/ data collection in the age of online research. Even the group of us posting here on Savage Minds thought of this exercise as a means of testing out ideas for a more conventional edited volume or some other such project.

Such approaches presume still that “ethnography” is happening (primarily? only?) in the conventional elsewheres, and not on the blogs themselves; blogs are after all tools to other (more standard) ethnographic ends. I’m suggesting, however, that blog-like spaces compel us not just to de-center classic ethnographic writing, but also to more fully embrace the notion of ethnography as process rather than (just) product.

My own admittedly fledging venture into blogging was born of a desire to situate myself in Pondicherry, intellectually, gastronomically, aesthetically—albeit without letting go of my anthropological tethers, which appear never really to have left Houston. Pâticheri is an experiment in re-claiming ethnographic voice in the context of repatriation, in a way that melds auto-ethnography with cultural analysis, and representations or performances of (in this case) food practices. It’s actually deeply gratifying that (1) my audience is not only academic, even when academics are readers, and (2) readers have far more participatory room here than in my prior work–indeed the line between those being written about and those reading is almost non-existent, just as “ethnography” is at times quite marginal. Some readers make it into a technical how-to site (which reflects at times just how esoteric aspects of culinary praxis remain): Send a recipe for digestive biscuits! What on earth do you do with this gourd that has these striations on it? How do I cut a mango? Others are gawking at images of food, or drawn to narratives about the repat experience, refracted through food practices. Moms ask about how long you can store homemade playdough; others reference Bourdieu. As with the work with the NGO, not all of it is ethnographic—but some of it explicitly is about thinking through social categories and cultural politics, about the social life of objects, or the major cultural (gender, design, labor) shifts that can be tracked through individual tools or practices.

Here the blog is not so much a tool for data gathering, as a collection site that is sometimes more, sometimes less analytical. It’s a place where ingredients are assembled, where curious juxtapositions can make for analytical opportunities, or in which quotidian (though not necessarily marginal) elements, like snacks, can become clues to understanding wider, more complex, or far-flung phenomena. It’s a place of conversation, a virtual kitchen table even. Writing is still central, but sometimes not as central as other media/ objects: the graphics, a music video produced by three random Pakistani guys, a curious fruit, the experience of a new Indian restaurant, the recipe that caps it all off. After all, we’re told, this is the attention (deficit) economy (see Lane’s post on this also); lengthy writing is less likely to draw people in than other, more visually oriented elements. We’re usually prompted to feel despair at such a state of affairs. But perhaps, just perhaps, some new creative ethnographic spaces might open up as a result?

Food blogs are these days are about as precariously poised as adjuncts: they may get noticed and paid (usually modestly, unless you’re developing iphone jailbreaks on the side or exercising “franchise” options by writing cookbooks or giving talks) or not read at all. But for all that, and especially for me, they’re a space of free play, one whose existence requires only minimal justification in terms of research strategy, and one which can simultaneously engage multiple audiences, both within and without the academy, and that on multiple levels (as parents, cooking enthusiasts or novices, collaborators, students, peers, friends, fellow artists or lovers of food writing and more)—thus being of the field in ways that our specialized mono-graphs and conventional outputs so rarely are. And it’s a work-in-process end-product, unabashedly. In short, it’s everything my dissertation, my book, and just about all the professional outputs I’ve had were not. (What a relief!)

To bring this somewhat meandering discussion full circle, there is this one element of “ethnography” that I’d add to Carole McGranahan’s list: a commitment to process over product, and the decentering of the writing practice that seems the so-natural consequence of all our ethnographic undertakings. Such commitment is perhaps nothing new, but I cannot help but wonder: Would I have been blogging while I was full time faculty—in between administrative meetings, and eternally preoccupied with making a list of work done that could, with self-respect, be presented in my annual reviews—or else? Possibly, many of my colleagues have long been active bloggers, though the ethnography of that blog would have been of entirely another character if I wanted to claim academic mileage out of it. Would I have been able to see figures like Ree Drummond or David Lebovitz as guides and inspirations over, say, Levi Strauss and Appadurai? Ha! Would illustration have been so central? No. That’d have been in the realm of “the hobby,” a cute but extraneous adjunct (I use the word deliberately) to the ethnographic process. Would it have been possible to juxtapose “Aaloo Anday” with Nancy Ries’ “Potato Ontology” with Pakistani political satire and a recipe for Aalu Anday Salan? Sure, but I suspect that would have been better classroom strategy than ethnographic method in its own right.

Not to gloss the fact that financial uncertainties loom as never before, that “fieldwork” is an increasingly absurd demand in new ways, that I’ve no idea at all if blogging is a worthwhile exercise. I’m also not at all sure if what I’m crafting in each successive post counts in anyone’s eyes but my own as “ethnographic” at all. But it sure is fun to pretend. And to explore, in between so many other conventional undertakings, an alternative realm of some modest possibility.

Deepa S. Reddy is Adjunct Associate Professor of Anthropology at the University of Houston-Clear Lake. She blogs on food, culture, and gastronomical life on Pâticheri: Ethno.graphic.Food