Jobs is an excellent example of the way a social imaginaire comes into form through corporate performance. Philosopher Charles Taylor calls social imaginaires “the way people ‘imagine’ their social surroundings, and this is often…carried in images, stories, and legends.” This notion goes back to Sahlins’s “charter myths,” B. Anderson’s “imagined communities,” and Ortner’s “serious games.” Social imaginaires are internalized and form a range of practical responses not unlike Bourdieu’s “habitus.” Anthropologists are good at recognizing the mental hardware that drive action. This may be a product of our emphasis on para-biological motivation (“culture”) as well as our methodologies. Look at the emphasis on narrative in the works of Richard Sennet and Paul Rabinow, both investigating the new economies of technology through subjective stories about work and its meaning.

Anthropologist Chris Kelty, influenced by Taylor, carried the imaginaire into the world of technology with his notion of the “moral-technical imaginaire” which is a cultural situated and persuasive moral philosophy attached to the use of both open and proprietary systems. Patrice Flichy in his book Internet Imaginaire uses the work of Paul Ricœur to show how utopian and ideological discourse are two poles of a technological imaginaire. The original euphoria of a technology is utopian, as that fades, the imaginaire is mobilized to hide or mask the ideological and dominating potential of the technological assemblage. More recently, sociologist Thomas Streeter, discusses how “romantic” imaginaires of ruggedly individual hackers, inventors, countercultural tramps, and psychedelic engineers helped to encourage the federal funding and venture capital that built the infrastructure of the internet. Finally, the most accessible of these accounts of internet imaginaires is the work of Vincent Mosco who simply refers to the myth of technological transcendence with the idea of the “digital sublime.” The transhumanist movement is ripe for such an analysis.

Certainly Jobs is not that which is performed. Apple and complicit tech journalists have done everything to maximize the illusion of Jobs as master auteur. It fits a neat trend in technology history. First there was Marc Andreessen, the boy wonder of Mosaic/Netscape and the internet bubble of 1994-2000, photographed barefoot on the cover of Time in 1995 at the dawn of Netscape’s IPO. The hype surrounding him fomented in a rush on the NASDAQ and its soon collapse. Consumers were left with an awesome internet infrastructure because of the build up but also with a generation of creative workers and investors who lost their jobs and millions of dollars. Most of the educated and middle class information workers got back on their feet and are enjoying the Web 2.0 bubble only partially squeezed by the global financial crisis of 2008. The point is that social imaginaires are not just in our heads.

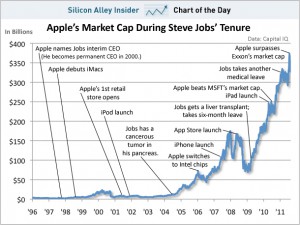

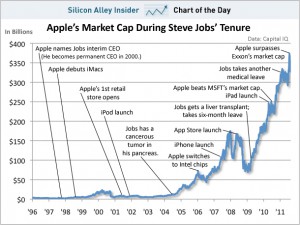

They have real consequences. Apple got filthy rich and Jobs too. Despite taking only 1$ as an annual salary (what a saint!), his stock options at Apple and Pixar total over $8 billion. Apple surpassed the US Treasury’s total bankable savings and peaked over oil giant Exxon in market cap both this year. Secondly, Apple’s mythology has a lasting legacy as a dominant player in the promotion of closed platforms and monopolistic power.

Tim Wu, best-selling author of The Master Switch: The Rise and Fall of Information Empires, and coiner of the term “network neutrality,” says he fears Jobs above Zuckerberg and other information mavens. He describes Jobs’s imaginaire and its power: “Steve Jobs has the charisma, vision and instincts of every great information emperor. The man who helped create the personal computer 40 years ago is probably the leading candidate to help exterminate it. His vision has an undeniable appeal, but he wants too much control.” Despite Jobs being metaphysical, his impact is fiercely physical.

Despite his utter

disdain for philanthropy and open systems, I hope Jobs is healthy and lives a long retired life but I fear his legacy. Stay with me here, I love the

2005 Stanford commencement speech, too. The part where, after dropping out of Reed College and while dropping in on classes, he begins to notice the fantastically efficient and yet elegant calligraphy everywhere–that is pure theatrical genius. What an origin myth for the smooth coolness of my iPhone! Jobs’s saintly genius is a carefully orchestrated performance by Apple, tech journalists, venture capitalists, and MacBook fanboys to create an illusion that we are blessed to be typing away on technologies of such holy grandeur. As this narrative grows so does Apple’s stocks. Social imaginaires like that which circulate around Jobs are stories we tell ourselves about ourselves with real impacts in the world.

Apple products are great, I’m using a couple right now. But the spiritual intonations describing Jobs’s role in the production of these easy to use, trendy, flashy, and expensive devices is overstated for a purpose. The auteur visionary, who throws off tradition, rises from the ashes and returns, and kills a rigid bohemoth (Gates) are all narratives that help to sell products and stocks. These stories encase the casings of Macbook and iPads with a genius virus that users mistakenly think is contagious. I am going to go out on a limb here and say Apple products were not necessarily the best systems for the design and film production worlds, it was the narrative of Jobs as sympathetic master that made the creative industries believe that Final Cut Pro was necessary. Us filmmakers and designers wanted to be in on the magic. Eventually FCP and Quicktime became their own standards and we all were stuck using Apple products.Jobs is a hallucination with physical properties. There is no better illustration of this then how the market responded to Jobs’s illnesses. In mid-2009 Jobs got a liver transplant and took six months off, Apple’s market cap plunged $100 billion. Earlier this year he took another medical leave and again the market cap dove. Rational markets?

Look, call me unimaginative but I want to live in a world whose major systems–government and markets–are ordered by consensual rationality. We currently have a spate of GOP candidates that both think the market is rational and that global warming and evolution are hoaxes. This won’t do and is alike the hype surrounding the myth of Jobs. Both Jobs and the GOP are irrational and the result of journalistic laziness and consumer dupability–a legacy of the increasing subsumption of neoliberalism into all walks of American life. If anthropologists got access to tech firms such that sociologists David Stark, Gina Neff, and Alexander Ross have, and showed that design is a collaborative and multi-authored act, we wouldn’t be so easily manipulated by the digital sublime. If the computers in front of us weren’t black boxes, and we could program instead of being programmed, as Douglas Rushkoff says, by corporate supported and irrational imaginaires, then I think we could move closer to a critically discursive public sphere. I want to see imaginaires as they are, necessary mythologies, while at the same time I want to trim away the fatty and unnecessary hyperbole around their edges.

People love musicians, glorify them, overlook their inadequacies because musicians often bring joy into people’s lives.

Steve Jobs did the same but with technological products.

James Brown invented the funk, completely changed the game, and for that he was lauded despite his many inadequacies, but the fact remains: James Brown changed music and brought countless joy into people’s lives.

Steve Jobs did the same with Apple.

My point: master auteurs exist in various fields, i.e. one person really can be that much more impressive in a given field. Sure, over the top praise for that one person is ridiculous, but it’s a very human thing to do, and should not at all detract from the achievements of that master auteur.

I mean, do you really think Jobs had nothing to do with making the iPhone? That it was something that any other company would have done so elegantly?

Do you believe no master auteurs exist, or just that Jobs isn’t one?

It is about prestige and status. Words like “auteur” have a place in the analysis of the narrative, but not anywhere else. It is not about whether he really is one or not, it is about the consequences of people believing he is one.

Pragmatism is the foundation for anthropology, so let’s use it 🙂

1. If you’re looking for examples of irrational markets, Apple’s not a very good example. Deciding that Apple without Steve Jobs is not a good investment might end up being the wrong decision, but it’s hardly irrational. Steve Jobs has certainly been mythologized, but CEOs aren’t just seat-fillers; they actually have a very real effect on the performance of a company. How is this even in question?

2. “Despite his utter disdain for philanthropy and open systems, I hope Jobs is healthy and lives a long retired life….” That’s very generous of you.

@Antonios, yes, I believe that no masters exist. The works of Steven Johnson, Kevin Kelly, and, more sociological, Thomas Streeter, not to mention Kuhn, confirm that good ideas travel in historical and culturally situated packs. If not Steve there would be another Steve, maybe Javier, or Amit…. Its kinda mystical but paradigms or practice and thought occur. And I agree “it’s a very human thing to do” to create myths about gods of mountains or technology. That is why this is an anthropological blog.

@Robin, yes, I overdid the auteur reference, I couldn’t stand my French Film theory course and grew to hate those Bazinian auteurs, hence its term of derision. I’d like to know more about this pragmatism, I like to think I work in a pre-theoretical pragmatic paradigm. You?

@John, I disagree, Apple is a key example of consumer fanaticism generated by mythology and folklore. So rich and so hyped up, no better example. Yes, CEOs have a real effect, but that effect is not the result of Jobs’s job performance as a designer or coder but as a totem.

@Adam I think you’re wrong. Masters do exist. They don’t exist because they spring from the gene pool with superior talent. That is only a necessary condition, not a sufficient one (see Malcolm Gladwell’s Outliers). They are talented people who find themselves in situations and pursue careers in which setbacks are overcome and success builds on success. The hugely successful, like Jobs, not only succeed themselves. They create institutions that create opportunities for others like themselves. And in some way, great or small, they do change the world. The rest of us may do OK. We may even be pretty smart. But we’re not in that league.

The two examples you initially gave of market irrationality were dips associated with Jobs’ medical leaves. If any CEO abruptly resigned, died, went on medical leave, was sued for sexual harassment, etc. that would be a good time for shareholders to re-evaluate their holdings in the company. This would be true for any company, but especially so if the CEO is a founder of the company and the company is focused enough that the CEO can be highly involved in all areas of the company. So if the CEO of Kraft or GE went on medical leave that should make shareholders concerned. If the company is Wynn Resorts or Berkshire Hathaway or Apple, that concern can quite rationally go up. I’m defining an irrational decision here as one that’s wrong based on the information available to the trader at the time of the transaction. This means that a market decision can be wrong without being irrational.

The third example of irrational market behavior is apparently that Apple is “rich” and “hyped up”. Apple’s worth as a company has gone up sixfold in the last five years. That’s really good, but it’s not so unusual that it requires a special explanation that doesn’t apply to every other company. This year, IBM’s performance is just behind Apple’s. How many people can name the CEO of IBM off the top of their heads?

The far simpler explanation for why Apple’s stock has increased sixfold is that Apple’s now six times larger as a company than they were five years ago. They regularly beat earnings estimates, they sell highly profitable goods and services, their P/E ratio is good, they have no debt and they have an enormous amount of cash on hand. That looks like a solid company rather than hype to me.

Again, the markets are full of irrational valuations and decisions, but I’m not really seeing it at Apple. Where, specifically, are you seeing irrationality?

In regards to the CEO as totem, what exactly does a totem do at the office all day? Recently, Leo Apotheker decided HP wouldn’t sell tablets anymore and was going to sell off it’s PC and laptop decisions. I choose this one specifically because it’s a decision that can be attributed directly to the current CEO. Mark Hurd doubled down on PCs, that never would have happened with him at the helm. It’s a very real decision that will permanently effect what the company does and how it makes money. Steve Jobs made decisions like that all the time. That isn’t myth-making or a media conspiracy. Look at how many patents have his name on them. Steve Jobs was pretty clearly focused on just about everything Apple did. I get what you are saying about multiple authorship and collaboration, but Jobs is the one who chose the authors and told them what to create. Even if he wasn’t personally coding, he was often one of those authors. It’s not about “good ideas”, it’s about great execution of good ideas.

(p.s. Since I talked so much about stocks here, in the interest of full disclosure, I don’t own stock in any of the companies mentioned.)

(p.p.s. Actual examples of current irrational markets: Beyond-Thunderdome types getting spooked into sending gold prices through the roof, the perfect storm of incorrect valuations that has lead to the NBA lockout.)

@John. I feel the more anthropological approach is to see ideas traveling in historically situated packs, path dependent upon previous occurrences. Cultural contexts within historical contexts create the fertile environment for a ‘genius’ to emerge and thrive. The individual is so dependent upon culture and history, and in this case, technology, that the individual runs the risk of being irrelevant. I am potting this rather grossly but this is the insight of Steven Johnson’s Where Good Ideas Come From: The Natural History of Innovation, Kevin Kelly’s What Technology Wants. Johnson’s book is a catalogue of inventions and how time and again, in the invention of radio, calculus, light, flight, computer, etc. there were more than one inventor at the same time inventing the same thing separated not by time but space. Its a little mystical if you don’t think about it from the perspective of anthropology. Kelly gets all into the mysticism and thinks technology, what he calls the technium, or technologies own reflexive desire to evolve, is to thank for the subservient humans making and remaking itself at the same time. Sociologist Streeter says in the Net Effect, “ideas emerge within communities. There are unique individuals who make important contributions, but those contributions generally rwo out of, and are nurtured within, communities that share a system of thought or inquiry. Newton discovered calculus, but it is hardly a coincidence that Leibniz came up with the same ideas at roughly the same time.”

Now a historiographer like Sewell theorizes ‘events’–cultural transformation that modify the trajectories of human history. These do exist but they are not the product of single geniuses like Jobs.

@Adam This is an argument like the old nature-nurture thing. No one aware of the evidence believes that explanations are 100% nature or 100% nurture. In a similar way, no one not ideologically committed to a blind egalitarianism can take seriously the notion that because even genuinely talented people don’t create ex nihilo that they don’t add anything special to what does happen.

Can you play basketball like Michael Jordan? Could you dance like Michael Jackson? Paint like Picasso? If you allow the importance of talent (not saying that it’s everything) in sports or the arts, why not in design or management?

P.S. The idea that “ideas run in packs” is packed with misplaced concreteness. Why not “ideas float around like jellyfish”? Or “Ideas lie around like pottery fragments in middens”? Why is it that when cases of independent invention occur, they never involve more than two or three people, all of whom turn out to be genuine geniuses: New and Leibniz both invent the calculus, Wallace and Darwin both come up with the theory of evolution….What does that say about the millions of people alive at the same time?

P.P.S. Newton and Leibniz.

Adam, I think you’ve made an error.

I agree with you that ideas move in culturally and historically situated packs. But here’s why the master auteur is important: if I’ve got money that I want to invest in technology because I see that a bunch of ideas are ready to be generated, I could invest that money in a company run by someone like Steve Jobs at Apple or in a company run by some dull MBA.

Clearly, Steve Jobs is the difference. Some hack MBA is not going to make the iPhone happen. Some hack MBA is going to be making PowerPoint slides while Steve Jobs gets cool stuff made.

That’s why people love masters. Sure, some other people might come up with the same idea at the same time, but those people are a small set of all the people in the world. Although it’s unfortunate that generally only one person gets the credit, they still deserve the credit and adulation despite the fact that a select few others did or would have come up with the idea anyway.

I would add to what Antonios says that mastery isn’t just about having ideas. Its about an obsession that refuses to give up and insists on having every detail as perfect as perfect can be, plus the charisma and leadership ability to infect people with the same vision.

We live in a world where ideas are a dime a dozen. The ability to implement them and build institutions around them—that remains exceedingly rare. And that is where true mastery lies.

You’ve all made excellent points. And the discussion has fleshed out a nice defense of visionaries versus my account of social imaginaires. Between the two issues we are beginning to see the simultaneous social and individual construction of genius or technology trajectory altering events. I am still left feeling a bit challenged by whether anthropologists can actually investigate inventors with the pro-agency, pro-leadership theories you guys have put forth. It is becoming a bit more of a psychological or institutional analysis as opposed to an anthropological one–as you seem hell-bent on defending individuality, in this absolutist Lockeian or Smithian or Bazinian way as oppose to one more grounded in social constructivism. So be it.

I’m going to stick to my guns that the iPhone and iPad not only kinda suck but were being developed in every telecomm company in the Valley previous to Apple beating them to market and every sci-fi writer’s desk from the 1960s onward; that Jobs was a performance with a bevy of unnamed and more brilliant workers pooling their ideas to make consumer fetishistic products; and that he exhibits no more exquisite qualities than any other countercultural capitalist in the Valley.

Jobs is by no means singular, but did more than step in a lucky pile of shit. So what if the general public misappraises him? The general public doesn’t know much about how most things work.

MTBradley makes an excellent point, “The general public doesn’t know much about how most things work.” Neither I would add do most people who write about social theory or cultural studies. Their conclusions are like those of theater critics who may have seen a lot of plays but have never been backstage. Thus their ideas are forever stuck at the level of fetishized images. I note, re Adam’s last remarks, that both “visionaries” and “social imaginaries” are typical of concepts stuck at this level. If the one is a relic of theories of genius in which the the genius is likened to God, the creator ex nihilo of something wholly original, the other is a relic of viewing culture as wholly super organic, a given to which they can only passively react instead of being active agents who can play significant roles in reshaping what they are given.

iPhone sucks? That’s crazy — clearly you never used a phone before the iPhone happened.

Furthermore, by your line of reasoning, you could argue everyone was doing online search — there was AltaVista, Yahoo, Ask Jeeves etc. Online search is no big deal, Google didn’t do anything new and blow their competitors out of the water, there’s nothing Google did with their search that was better than anything else…

Interesting post!

The ‘individualists’ should check out some ANT work. Steve Jobs did not create the iPhone. Who actually did create the iPhone? What was involved? ‘Steve Jobs’ is an event that is repeated in different ways throughout the Apple empire. Separate the person from the different dimensions of the event (media event, market event, design event, fetished commodity event, etc.).

This post has more to do with the way markets are imagined and the role bestowed upon CEO’s to attempt to shape the ‘market’ response to a company’s activities, which is normatively irrational.

@glen

IMHO, people who go into that down-my-nose “people should check out X” mode should do a better job of keeping up with the field.

“In the 1990s, Latour abandoned ANT, ceding that the objections others had raised to it—that it was reductionist, and that it prioritized knowledge, science, and technology as the driving forces in all cultures—were in fact accurate.”

http://www.indiana.edu/~wanthro/theory_pages/Latour.htm

imaginaires?? imaginaries. modern social imaginaries. imaginaire does sound like a cool fridge or something.

Taylor and the other anglophone folks do use ‘imaginary’ or ‘imaginaries.’ There’s an older term in cultural and historical analysis, l’imaginaire, that comes out of the Annales school and developments in what was known as l’histoire des mentalités. See in particular the work of Jacques Le Goff or Georges Duby. I’m actually not sure if Taylor and the other anglophone folks referring to ‘social imaginaries’ cite the Annalistes as important precedents for their work.

@john

LOL

Keep up with the field? Ok, then I won’t link to pages clearly written in 2006 (April 28?) like you have done in your comment!

There has been vigorous discussion around Latour’s work, including ANT-derived concepts, over the last few years.

Latour’s quasi-Foucaultian points about the networked character of the constitution of knowledge and the distribution of agency have not been abandoned, rather they’ve been largely absorbed.

And who, precisely, gives a damn? No, that’s too rude. Why should one care?

“In the 1990s, Latour abandoned ANT, ceding that the objections others had raised to it—that it was reductionist, and that it prioritized knowledge, science, and technology as the driving forces in all cultures—were in fact accurate.”

???

Latour published Reassembling the Social: An Introduction to Actor-Network-Theory in 2005?

I suppose I am interceding at an awkward moment, though I find the question “Why should one care?” quite disquieting. “In order to understand,” I suppose? Whatever problems you have with Latour and the hipster vibe of him and his ilk, he does pretty good empirical work on actual science and technology I think. If Latour spent a decent amount of time writing a book on Apple and Steve Jobs, I would wager I would learn quite a lot more from it than from any number of Wired articles fawning his “genius” or business-school-speak pieces on utilizing innovation principles for successful product integration.

No problem at all with Latour. Only with those who make looking down their noses comments while displaying considerable ignorance of what they are talking about.

If I may ask an empirical question, I would like to know how big the circle is in which Latour is a focus of interest and much of what he has written, e.g., about ANT has been absorbed into common knowledge. I ask because i read fairly widely and rarely see him mentioned outside of discussions like this. That could reflect nothing more than the directions my reading takes me and the thus inevitable blind spots in what I know. On the other hand, it could be that his work is venerated only in a small circle whose members think that what he’s written is the greatest thing since sliced bread. Out of sheer curiosity, I’d like to know which.

It turns out, by the way, that Reassembling the Social is available online in PDF. It was easy to locate and download. Reading the introduction I discover to my delight,

I may be forgiven for this roughness because there exist many excellent introductions for the sociology of the social but none, to my knowledge, for this small subfield of social theory8 that has been called—by the way, what is it to be called? Alas, the historical name is ‘actor-network-theory’, a name that is so awkward, so confusing, so meaningless that it deserves to be kept. If the author, for instance, of a travel guide is free to propose new comments on the land he has chosen to present, he is certainly not free to change its most common name since the easiest signpost is the best—after all, the origin of the word ‘America’ is even more awkward. I was ready to drop this label for more elaborate ones like ‘sociology of translation’, ‘actant-rhyzome ontology’, ‘sociology of innovation’, and so on, until someone pointed out to me that the acronym A.N.T. was perfectly fit for a blind, myopic, workaholic, trail-sniffing, and collective traveler. An ant writing for other ants, this fits my project very well!

I must say that I do like the way Latour writes.

Hrmmm, I suppose it depends on what you see as discussions like this, how much influence is a big influence, and how much of his written stuff needs to be used to qualify as a Latour focus. It is a rather difficult question to answer precisely.

For example, there is work on “ontology” (interestingly, I just googled and found there was a savageminds post on it! heh! /2009/05/08/towards-an-ontological-anthropology/), which is quite directly based on work from, among others, Latour. From a UK perspective, this ontology thing is at least on the agenda for quite a few people.

Also, from what I understand from others I know, he is also picked up in anthropology of law. But that’s not really my specialty… and I get this is true for many kinds of subfields, quite outside science and technology, that have picked him up. But not my area.

The general gestalt sense I think is that he is one of those figures that most people have read and “absorbed” to some extent, in a way similar to Strathern. Perhaps like glen above, there is a a distinct minority that thinks he is the “greatest thing since sliced bread”.

So I suppose the answer to your question is both: he has been sort of generally accepted into the “common knowledge” that informs many contemporary conversations across a wide variety of sub-fields, while also being a sort of messiah figure for a select few who are into that sort of thing.

Yes, I agree that Latour does express ambivalence towards the term actor-network theory. I can’t remember if it is in this book, but he does say somewhere that there are four things wrong with the name: the word “actor,” the word “network,” the word “theory,” and the hyphen. Like you said, this is the amusing way in which Latour writes. Nevertheless, it would be misleading I think to say that he “abandoned” ANT or to imply that we have moved on from such old fashions… I can understand its your annoyance at the way it was put forward to you, but I won’t let you get away with throwing the baby out too! 😉

Throw babies out? Not me, I am a granddad whose grandparent gene has been fully activated. I dote on babies wherever I encounter them.

The original discussion, however, was not about Latour. The topic was the apotheosis of Steve Jobs. One can hardly deny that Jobs did not achieve his success without the help of others and previous knowledge on which he built. But the usual arguments along the lines of “the ideas were in the air, someone else would have done it” and the usual hackneyed examples, Newton and Leibniz and the calculus, Darwin, Wallace and natural selection, fail as attempts to reduce extraordinary achievement to something anyone might have accomplished had they been given similar opportunities.

In Apple’s immediate environment, figures as diverse as Bill Gates (Microsoft), Larry Ellison (Oracle), Scott McNeally (Sun Microsystems), and Larry Page and Sergy Brin (Google) lived through the same era, had access to the same ideas and information, and did radically different things with them. Most damning of all to this kind of sloppy argumentation is that millions of others failed to do what Steve Jobs did. No amount of hand waving and “blind, myopic, workaholic, trail-sniffing, and collective” analysis will change those basic facts.

ANT may enrich our understanding of what Jobs accomplished and how he managed to accomplish it. To use it to deny his accomplishments is piss-poor example of sour grapes and deserves to be treated as the piffle it is.

What are his accomplishments that are being denied? Let’s step back stage for a second, like you suggest, and think about how tech companies really work. What is Apple? It’s a large corporation, with how many employees, offices, intranets, call centers, and research laboratories. Maybe if we peek inside we can see who all the actors are that contributed to the iPhone, the engineers and the marketing people, the computers and the infrastructures, the casual lunches and the boardroom meetings, the markets and the regulations. Would we find that “Steve Jobs created the iPhone! (admittedly with a bit of advice from his friends)” or would we find a more ANT-like story, where Steve Jobs is one important actor among many, many actors, in a space where accomplishments are controversies that stabilizie and destabilize? Would we find that it is 1) Steve Jobs is a genius mastermind who was the only person who really mattered (individualist) 2) Steve Jobs is an irrelevant placeholder since the ideas were already free-floating around (culturalist) 3) we can’t predict what the answer would be before we actually look except to say that both 1 and 2 are almost certainly wrong and simplistic (ANT)?

Anybody’s guess I suppose. Where’s your money at? It would be fascinating to read an actual empirical study…

An actual empirical study would be great. Thinking about how to conduct one would be a marvelous exercise. Three critical issues are (1) access — not everyone with something important to say will be willing and able to talk to the researcher; (2) there may, in fact, be no one who knows the details of every step in the process – I’ve written about this in an article on creating advertising in Japan, where not everyone is present at every meeting and a lot happens in hallways or private encounters between key players; and (3) myth-making — in the same article I note that the history of successful campaigns is inevitably edited and transformed into a kind of simplified Whig history of a strategy and brilliant idea successfully implemented. Once that becomes accepted dogma, the access issue becomes even more important. I’ve been lucky in my own research to have spent enough time employed by a major player in the industry that I get to hear anecdotes about how things really happened instead of the sanitized version PR departments insist on. I’d be lying though if I said I knew what really happened. All that I actually know is what a couple of individuals with their own particular perspectives, memories and axes to grind have told me.

All that said, I’d opt for a third hypothesis you don’t consider: (3) Jobs was a necessary but not sufficient condition for what Apple has done and become. That’s neither (1) a mastermind who, like God in Genesis, creates everything himself de novo nor (2) an empty placeholder without whose presence Apple would have done what Apple has done anyway.

P.S. It might be worthwhile to reconsider “genius,” a term that started out referring to a demigod and was later exaggerated to exalt individuals to the same level as the Judaeo-Christian Almighty God, which is, as we anthropologists know, not only blasphemous but a serious misreading of the human condition, dependent on others from birth.

Any ideas on how the woz and his work steering apple to jobs’ promised land of creative nirvana? I for one think woz was pivotal in focusing on not only what people need….but what they want,too.