I wanted to avoid writing about Japan in my first post on Savage Minds (because I do that all the time at my own blog), but alas I am a creature of habit. But I hope I will be pardoned: I’m reporting about an anthropologist in a major print publication. And this will be sort of a riff on Kerim’s earlier mention of the clever parody on the African village planned at a German zoo.

Anne Allison, a Professor of Anthropology at Duke University, is mentioned in this week’s the New York Times Magazine in an article titled “Love. Angels. Product. Baby.” The piece is written by Rob Walker, who regularly writes for the magazine about consumerism and the money-centric culture of the capitalist society we live in. His column, “Consumed,” is in the “Way We Live Now” section of the NY Times Magazine).

(By the way, here’s another anthro connection: in this interview, Walker describes his endeavor as a “hybrid business-and-anthropology column.” Hmm…)

Walker writes that popstar Gwen Stefani‘s new album, Love. Angel. Music. Baby, and the entire marketing carnivalesque surrounding it (including an HP digicam branded as “Harajuku Lovers“), can be summed up by this neat phrase: “the commodification of commodification.”

Stefani’s latest album prominently figures “The Harajuku Girls” and is a paean to Harajuku, a section of Tokyo known as a neighborhood where hip youngsters come out dressing up in the strangest mixture of goth, tribal, haut-couture, and seemingly every other trend in the world history of fashion. Along with Shibuya, which has more love hotels and generally feels a bit more “adult,” Harajuku is the testing ground for Japanese marketers trying out their ware: they know that if a product catches on among the young hipsters who loiter there, it will sell well and perhaps conquer the world.

To Stefani, Harajuku Girls are hip. Why does she think this? Walker clues us in:

What is unusual is tha Stefani does not seem drawn to this subculture by ideology, rebelliousness or even a dance style. She seems drawn solely to a group’s apparent skill as shoppers. The song “Harajuku Girls” is a cross between a fashion-magazine trend story and an expositional number from a Broadway musical.

So Stefani, whose earlier persona in her band No Doubt was the punked up bad girl who bansheed around and shouted her head off to ska beats, is now all starry-eyed about shopping for the latest trends. Walker continues:

So what we really have here is not just a pop star endorsing a product but a pop star paying tribute to a consumer tribe. The real star behind the camera is not Stefani, but a specific breed of global hyper-consumer — as translated by Stefani. […] It is the commodification of commodification.

At this point Walker cites Anne Allison as a critical observer of the way Japanese subcultural icons have been swept up by the global mediascape (she examines, for example, Pokémon, in an article in this book), and asks a loaded question: “But […] does that mean that Japan has a real currency now? Or is it just a cool brand?”

Walker’s article is insightful in many ways. But I have a few problem with his interpretation of the Harajuku Girls.

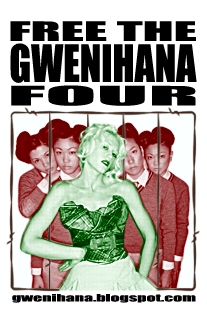

For one, I don’t think Walker addresses the fact that these girls are represented in an exploitatively orientalist manner. When Stefani came out with the Harajuku Girls back in April, the blogosphere was flooded with feminist and Asian-American critiques of how these four dolled up cyber-ghetto-geisha girls have become a harem-like accessory piece of a white girl (much of this criticism launched by a Salon article by MiHi Ahn and reproduced here by Howard French). The poster up top is a photoshopped expression of this critical perspective.

Yet there is another set of stereotypes being evoked here by Stefani, which has to do with Japan as somehow beyond the present, without history, and self-absorbingly capitalist in some techno-utopian state of bliss. This kind of thinking has its roots in Alexandre Kojève‘s oft-noted declaration that Japan is a post-historical society (retracted I think later in his life) and Roland Barthes‘s otherwise great masterpiece, The Empire of the Sign. (I won’t go into details here, and I know I’m reaching a bit if I claim that the following also applies to the Harajuku Girls, but this line of thinking also resonates with 1. Japan’s wartime fascist ideology, which cast Japan as already beyond the West and” post-modern”, and 2. the contemporary triumphalism of neoliberal economics as in Francis Fukuyama’s The End of the History.)

A few years back Japanese critic Toshiya Ueno, writing about Japanimation, called the representation of a technologically utopic Japan as “Techno-orientalism.” In the case of the Harajuku Girls, some “consumer-orientalism” may be at work: a representation of a nation and its people as serious shopaholics to the point where girls would be willing to “whore up.”

Walker, whose sole criterion for judging good products seems to be “about figuring how to remake a subcultural style into something salable on a mass scale” (from the NYT Mag article), joins Stefani and her marketing team in celebrating this “commodification of commodification.” He understands that commodification involves not only buying (such as the act of girls accessorizing) but also selling. Yet he seems unfazed about what it is that they’re actually selling.

Walter Benjamin, in “Paris, Capital of the Nineteenth Century” writes of the prostitute as a figure of pure commodity: “a saleswoman and wares in one” (Reflections, p.157). It is difficult for me to not see these Harajuku girls as a similar figure of the prostitute as commodity, one that mixes racism, sexism, and the technologies of consumption into one bold entertainment package.

Now whenever a blogger debunks exploitative images in mass media, someone has to make a comment that is a variation of the following: “this is only a video/movie/pop song, so don’t take it so seriously.” To this I reply: I am not the one who might take this seriously, but rather the little boys and girls watching Stefani videos and taking in all this stereotyping as reality.

I’m usually not one for identity politics. But the Harakuju Girls is just a bit too over the top for me. So what do y’all think, am I just over-reacting?

I’m in Tokyo right now, and I can keep thinking to myself how much Stefani blows Harajuku way out of proportion. Her vision of Harajuku is totally not reality. That being said she’s really only doing what the Japanese have been doing for a decade now. The Japanese have this tendancy to take a cultural prototype, strip it of all the cultural and historical significance, and wear the shell as a cool new fashion. It sounds horrible to us, but its really not as bad as it comes across. They dont care about actually becoming African, American, German, French, etc., they just like the look. It only gets to us because we’re the ones being “ripped off”. I’ve had an African American girl in my class who got so annoyed by the superficial nature of the popular Japanese expression of hip-hop. She says the style and the ethos are inseparable, but shes wrong. They are separable, and the Japanese separated them, because they dont have the cultural baggage that we do with regard to civil rights and whatnot.

Anyway, the point is this, what Stefani has done with her cultural zoo of Harajuku girls doesnt fly in America because we see this kinf of commodofication of a cultural persona as a rascist/sexist thing. I havn’t got a chance to talk to many Japanese people about how they view Stefani’s Harajuku fetish, but my hunch is that they see nothing wrong with it, because they do it all the time themselves. That doesnt let Stefani off teh hook in the US though, and I’d really like to punch her in the face if anyone could get me close enough 🙂

Itsalljustaride: Punch her in the face! Yipes!

Tak — I totally am sympathetic to what you are saying, but at the same time I wonder how much of the audience for Stefani’s music even gets that she’s actually ripping off a specific cultural anything. Her whole look and style is sort of a mishmash of elements (Marilyn Monroe! Ska! Harajuku!) but where these things come from or what they might represent are probably pretty fuzzy around the edges for a lot of her public — I think she gets it, and smart commentators in their 30s (or 20s, wherever you are) get it, in a different way than the kids at home get it. they probably think “sexy Asian chick” (has its own problems, of course) rather than “hmm, I never knew *that’s* what contemporary urban Japanese girl culture looked like! golly!”

I would agree with you Ozma, with the exception that Harajuku is only a small facet of “contemporary urban Japanese girl culture” and young teens in America have this bad tendancy to latch onto symbols like Stefani’s and assume that it represents the norm in Japan, when Harajuku is actually the anti-norm. I know, because I did it when I was a teen watching anime all the time. I always thought anime was this great representation of Japan, but then you start to realize that that position is as silly as saying “Friends” or “Sex in the City” is a good representation of America.

I’m a little skeptical as to whether *anyone* in the U.S. is really reading “Japan” from Gwen Stefani, at least outside the pages of a few publications.

A few other comments:

–Stefani is continuing a pop-orientalism that goes back at least to Janet Jackson (“If” video) and Madonna (“Nothing Really Matters”… “Rain”… )

–Is *Stefani* doing any of this or is it really just an *army of stylists* at work? (I think the latter actually.)

–I love the contrast drawn above between the ardent moralism of American attitudes toward cultural exchange (‘You can’t re-appropriate that (e.g. hip-hop, voguing, new age spiritualism)’ it *belongs* to us!) versus a world in which people freely exchange styles, ideas, dances, practices, and other cultural stuff because it inspires them, because they think it’s *cool*, a mode of cultural appreciation that has been popular even outside capitalist consumer culture for epochs (see, e.g., almost all the ethnography of Melanesia…).

For some politically and factually informed writing about youth-oriented marketing in Tokyo, and mass culture in Japan in general, I’d recommend this blog, at http://www.neomarxisme.com (apologies, I don’t know html). He also points out that Harajuku fashion in large part moves to the dictates of glossy fashion magazines and has little to do with ‘subculture’, in the way Dick Hebdige (or anyone else) uses the term.

i am doing a project on harajuku girls at college and i am so sick of people telling me that harajuku girls is not a fashion/trend they are saying that it is just a street has anyone got any suggestions so that i could try and change there minds?????????